New York City real estate is never short of mantras and catch phrases, but few have taken hold of the industry’s collective mind like “safe haven.” Seemingly no conference, panel discussion or research report can do without these two words. The notion that the New York market is a “safe haven” for foreign investors fleeing economic turmoil has become a guiding ideology for developers, investors and brokers from the Bronx to the Battery. Regardless of whether that claim actually has merit, it’s based on an undeniable trend: the significant growth in foreign investment in the Big Apple’s real estate market in recent years. And, many of these new investors are drawn here by the city’s comparatively stable prices, relative liquidity and easy accessibility. But what the true believers often fail to mention is that New York isn’t the world’s only “safe haven.” For today’s investors, the choice is no longer between buying in Midtown or Lower Manhattan. It’s often a choice to invest in one of a handful of global urban powerhouse cities, particularly New York, London and Hong Kong, but also Singapore, Paris and other so-called gateway cities around the globe. And like New York, many of these cities have seen an influx of foreign capital since the 2008 worldwide economic crisis. This month, The Real Deal stacked New York up against these other megacities in several key real estate investment areas, including luxury residential purchases, commercial trophy properties, retail investments and taxes. The goal was to figure out why investors would choose, or bypass, New York when deciding where to park their cash.

New York City real estate is never short of mantras and catch phrases, but few have taken hold of the industry’s collective mind like “safe haven.” Seemingly no conference, panel discussion or research report can do without these two words. The notion that the New York market is a “safe haven” for foreign investors fleeing economic turmoil has become a guiding ideology for developers, investors and brokers from the Bronx to the Battery. Regardless of whether that claim actually has merit, it’s based on an undeniable trend: the significant growth in foreign investment in the Big Apple’s real estate market in recent years. And, many of these new investors are drawn here by the city’s comparatively stable prices, relative liquidity and easy accessibility. But what the true believers often fail to mention is that New York isn’t the world’s only “safe haven.” For today’s investors, the choice is no longer between buying in Midtown or Lower Manhattan. It’s often a choice to invest in one of a handful of global urban powerhouse cities, particularly New York, London and Hong Kong, but also Singapore, Paris and other so-called gateway cities around the globe. And like New York, many of these cities have seen an influx of foreign capital since the 2008 worldwide economic crisis. This month, The Real Deal stacked New York up against these other megacities in several key real estate investment areas, including luxury residential purchases, commercial trophy properties, retail investments and taxes. The goal was to figure out why investors would choose, or bypass, New York when deciding where to park their cash.

The gap widens

Real estate in gateway cities has always sold at a premium, but in the last decade, the gap between top-tier cities and the rest of the world has widened considerably.

In London, the average price per square foot for luxury apartments has more than doubled since 2006. And in New York, prices are up by more than 50 percent in that same time, according to data from the UK-based brokerage Knight Frank. And that’s all despite the financial crisis.

On the flip side, the S&P/Case-Shiller Index, which measures home prices across the United States, is slightly below its 2006 level, while its U.K. equivalent has just barely risen.

As the gap has widened between these top global cities and the rest of the world, the competition between them has also grown fiercer. Indeed, for many serious investors, evaluating decisions on where to buy property often involves pitting these cities against each other.

And it’s not just megacities like New York, Hong Kong or London. Leonard Steinberg, president of the Manhattan-based brokerage Compass, said “other centers beside those” also draw interest.

Last month, during a panel discussion hosted by TRD in Shanghai, industry experts cited six U.S. cities — New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boston, Washington, D.C., and Chicago — in the top 10 for Chinese real estate investment globally.

While it may seem counterintuitive, there’s a growing interest worldwide in urban luxury real estate since the 2008 financial crash, which was, of course, closely linked to global real estate.

Analysts explain this by pointing to an intensified lack of trust in securities and other financial instruments.

“The legacy of the crisis was to extend a question mark over people’s reliance on financial products,” said Knight Frank’s global head of research Liam Bailey.

While real estate-based securities clearly played a big role in the 2008 financial meltdown, real estate in top international cities generally didn’t suffer as much as it did outside those cities. That earned these urban centers reputations as stable places to invest.

In addition, since the meltdown, central banks all over the world have implemented policies that are favorable to real estate investment.

“Debt has been cheap for a long time. That has encouraged people to invest in real estate,” Bailey said, pointing to the effects of central banks pumping cash into ailing economies around the globe and keeping long-term bond yields low worldwide. That’s not to mention that the Federal Reserve has kept short-term interest rates low in the U.S., which has also driven more investors into real estate.

Major cities have drawn a disproportionate share of investment because their real estate is more accessible and more liquid — meaning it can easily be bought and sold.

This flood of capital cannot be discussed without also mentioning the global trend of urban renewal, which has led to economic and population growth in several of the world’s largest cities, further driving up the value of real estate. “There’s underlying economic growth factors that have been hugely successful in global cities over the last 20 years,” said Yolande Barnes, director of world research at brokerage Savills.

Economists at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University analyzed U.S. housing-price trends in a 2006 paper, and identified a handful of “Superstar Cities” where wealthy people increasingly cluster, driving up the value of their real estate relative to the rest of the country.

“The wealthy live in corridors where they feel they can have an insulated enclave,” said Faith Hope Consolo, chairwoman of Douglas Elliman’s retail group. “They just like go to the same country clubs, and they want to live in the same neighborhood.”

But while most major global cities have benefited from the fallout of the financial crisis, some have attracted far more cash than others.

Luxury apartments: London reigns — for now

As more analysts warn of a crash in Manhattan’s luxury housing sector, market bulls often whip out a simple counter-argument: compared to cities like London or Hong Kong, Manhattan real estate is still a relative bargain.

And the data seem to prove them right.

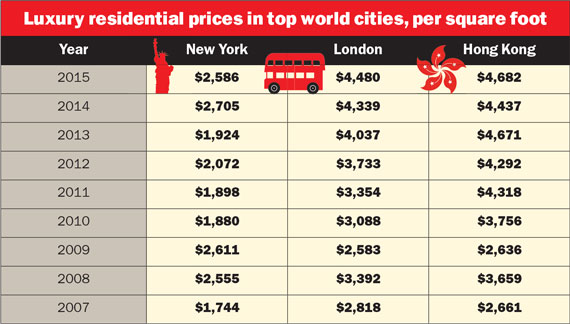

Hong Kong’s luxury market is the most expensive among the world’s major urban centers, with apartments selling for an average of $4,682 per square foot, closely followed by London at $4,480 per square foot, according to Knight Frank. Compared to that, New York’s average of $2,586 per square foot seems almost cheap.

But the latest annual figures seem to indicate that New York is catching up to its two biggest global competitors in terms of prices. And while Knight Frank identifies New York, London, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Singapore as the most popular among the global rich, it predicts New York will take over the top rung from London in the coming decade.

But the latest annual figures seem to indicate that New York is catching up to its two biggest global competitors in terms of prices. And while Knight Frank identifies New York, London, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Singapore as the most popular among the global rich, it predicts New York will take over the top rung from London in the coming decade.

The pendulum is already starting to swing in that direction.

In 2014, New York’s luxury real estate market saw prices jump 18.8 percent — the largest gain among world cities, according to Knight Frank. London’s luxury apartment prices grew by only 5.1 percent over the same period. And Hong Kong’s increased by a comparatively paltry 1.1 percent.

Meanwhile, Shanghai’s luxury residential prices stayed level and Singapore’s fell by 12.4 percent.

Prices have leveled off in New York City since then, according to more recent reports. However, in terms of absolute pricing per square foot, New York’s $2,746 per square foot average is still more expensive than Singapore ($2,392), Sydney ($2,277) and Paris ($1,846). But in terms of gross yields — the annual returns investors would make if they bought a luxury apartment and rented it out (not factoring in taxes and maintenance costs) — it offers more for an investor.

At 5.2 percent, New York’s luxury yield is second to Tokyo’s 6.3 percent, according to Savills. By comparison, London’s yield is 3.8 percent, Singapore’s is 3 percent and Hong Kong’s 1.8 percent.

For example, on average, a hypothetical $2 million apartment can be rented in New York City for $104,000 a year, or $8,666 a month, while in London that same apartment would only fetch an average of $7,600 a month.

For many investors, New York’s high rents help justify its high prices.

“New York’s prices probably look more reasonable [than London’s] now,” said an executive at a Chinese development company, who did not want to be identified but told TRD he owns two apartments in London and is now looking for one in Manhattan.

Yields are a good indicator of potential asset bubbles, sources say, because they aren’t distorted by exchange rate fluctuations and they show how prices correlate with market fundamentals.

If luxury yields rise in line with sales prices, the boom is likely based on strong economic fundamentals. But if, as sales prices rise, yields shrink to minuscule levels, price growth is more likely to be speculative, meaning it’s based on the assumption that prices will keep rising — or at least not fall. On this count, New York’s luxury real estate market seems less worrying than some of its peers, like Singapore or Hong Kong.

“In recent years, New York has shown much more value than London or Hong Kong,” said Emily Beare, a top-producing broker at CORE, although she added that could change.

Emily Beare

The strong market fundamentals in New York have been a driving force behind the current luxury condo construction boom. Developers will not build, and lenders will not lend, unless they believe that the buyers will ultimately be willing to shell out top dollar for condos.

“I think that everyone who buys real estate buys with the intention that it goes up [in value],” said Richard Jordan, vice president of global markets at brokerage Douglas Elliman. But he added a caveat: “At a certain high-level price point, it’s not just about the return anymore.” In other words: buyers care more about preserving money than making it.

While prices may be rising faster overall in New York than they are elsewhere, the question remains: Why are prices in London and Hong Kong today still so much higher than they are in Manhattan? Sources say that location is likely the primary factor.

“Hong Kong, over the last two decades or so, has been a really important conduit for investment into China — and money flows out of China,” said Savills’ Barnes. “From that point of view, it is probably the ultimate gateway city.”

London, meanwhile, is far closer than New York to centers of wealth in Asia, Europe and the Middle East. As a result, it has seen an influx of wealthy apartment hunters.

“If you look at the map of global wealth, London is just more convenient right now,” said Knight Frank’s Bailey.

However, notwithstanding the recent slowdown, the economic rise of China could shift the global center of wealth from Europe and the Middle East to the Pacific. That would work to New York’s benefit.

Chinese buyers are already among the most prominent investors in New York luxury real estate. (The exact extent of Chinese investment in New York residential real estate is unknown, because federal law forbids the collection of data on buyers’ origins.)

Bailey said he expects New York to overtake London as the most attractive destination for luxury apartment buyers by 2025, in part because of the strength of the U.S. economy. “London is slightly held back by the European economy,” he said.

In his research, Columbia’s Mayer found a direct connection between hiring among top companies and the increase in high-end apartment prices.

“Why does Google have to be [in] Manhattan?” he asked. “Well, the kind of people that Google wants to hire want to be in New York City.”

The strong economic growth in the U.S. has led to an uptick in hiring in New York, which could give it a slight edge over London. Employment growth in London has slowed recently after a strong rebound from the crisis — the number of people employed in July stood at 4.175 million, barely higher than the July 2014 total of 4.155 million, according to the U.K. Office of National Statistics.

Exchange-rate fluctuations are also key when it comes to the competition between international cities.

For example, the British pound has gained almost 10 percent on the dollar over the past year, meaning that apartments in London and all of the U.K. have become more expensive for some international buyers. However, that disadvantage is offset by a tax structure some say is less burdensome than its New York equivalent (more on that below).

Most observers expect London and New York to remain atop luxury buyers’ wish list for the foreseeable future. That has as much to do with language as with location: The four most expensive urban centers (London, Hong Kong, New York and Singapore) are either in English-speaking countries or have large English-speaking populations.

“Historically, and still, London benefits from the English language,” said Bailey, explaining that families looking to send their children to English-language schools are increasingly attracted to real estate in those locations. “Paris and Berlin don’t tend to benefit [to the] same degree,” he added.

The tax factor: Do investors fear NYC?

As Benjamin Franklin said: “In this world, nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” But when it comes to real estate (and nearly everything else) investors often do whatever they can to avoid high taxes.

So it’s not surprising that the tax landscape is a huge driving force for real estate investment.

Take, for example, Singapore. In late 2011, the government there introduced a stamp (or sales) tax on foreign buyers of up to 16 percent of a property’s value.

The move was designed to curb the boom in foreign investment that had driven up housing costs, and it had the desired effect. In the year ending June 2013, private home sales fell by more than 80 percent in the city-state.

New York’s mansion tax looks modest in comparison. Property purchases of $1 million or more carry a tax of 1 percent, a fee paid by the buyer.

That’s on top of a city property transfer tax of 1.425 percent on all deals worth $500,000 or more, and a state real estate transfer tax of 0.4 percent.

Mayor Bill de Blasio has proposed increasing the mansion tax threshold to $1.75 million — in recognition of the spike in median apartment prices since the law was implemented in 1989. But he also wants to raise the tax to 1.5 percent on deals worth $5 million or more.

While that’s expected to be a tough sell in Albany, where Senate Republicans oppose the tax hike, it’s actually a relatively small fee compared to other megacities.

“There is a real recognition by everybody that the frothiness and the strength of the condo market is something that New Yorkers should be able to collectively take advantage of,” Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen told the Wall Street Journal in May.

The proposal has drawn a mixed reaction from the real estate industry.

At TRD’s New York New Development Showcase and Forum in May, developer Ziel Feldman of HFZ Capital argued that developers “shouldn’t be in this business” if they can’t handle a mansion tax of

1.5 percent.

Compass’s Steinberg is more critical, arguing that the increase could discourage investment and have a boomerang effect.

“The idea is to raise revenues. If it ultimately reduces revenues [by slowing sales volume] it is completely counterproductive and simply stupid,” he said.

In London, taxes are staggered, ranging from 2 percent on property sales between roughly $190,000 to $385,000 to 12 percent on deals worth roughly $2.3 million or more.

“London’s property market came to a screeching halt for a year and a half leading up to the [2015 British parliamentary] election, because there was talk of property taxes being increased,” said Royce Pinkwater, head of the Manhattan-based Pinkwater Select, a firm that helps clients invest in luxury real estate. When the low-tax Conservatives won, Pinkwater added, the market kicked back into gear.

In Hong Kong, meanwhile, foreign buyers are subject to an additional 15 percent tax on residential property purchases — on top of the 1.5 percent to 8.5 percent that all buyers pay.

In Hong Kong, meanwhile, foreign buyers are subject to an additional 15 percent tax on residential property purchases — on top of the 1.5 percent to 8.5 percent that all buyers pay.

However, property sales taxes are just one of the many taxes that apartment buyers are subject to in all of these cities.

The list includes annual property taxes (which are tiered in New York depending on property type, but non-existent in Hong Kong, according to Knight Frank); income tax if buyers are classified as residents and capital gains tax for those looking to flip residential real estate. When you factor in all of those taxes, New York is no longer the cheap option, some observers say.

“London has lower taxes on dispositions, and is more tax-friendly for corporations,” said Elliman’s Jordan, explaining that this puts New York at a disadvantage.

Pinkwater added that foreign buyers in New York often fear they will be hit with a slew of taxes if they are classified as residents, although these worries are often unfounded.

“They are afraid they will be taxed on everything, including income; that it might impinge on their other assets,”

she said.

Office properties: Hong Kong’s prices are unmatched

Perhaps the biggest global real estate investment coup is landing a trophy commercial building. Buying one in a top global city instantly boosts an investor’s profile.

Manhattan lays claim to the two priciest on the planet for the first half of 2015 — the $2.2 billion sale of the Manhattan office building 3 Bryant Park to Ivanhoe Cambridge, the investment arm of a Canadian pension fund manager, and the $1.95 billion sale of Manhattan’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel to Chinese insurer Anbang Group. Those were followed by the third-quarter closing of 11 Madison Avenue for a staggering $2.6 billion.

New York also saw the most investment in commercial real estate (including office, industrial, hotel and multifamily buildings) in the first half of 2015, with a volume of $36.85 billion.

London was a close second with $29.7 billion, followed by Los Angeles at $16.9 billion, San Francisco at $15.9 billion and Tokyo at $15.8 billion. Hong Kong had a quiet six months, with a mere $4.1 billion of activity, ranking 22nd globally.

The popularity of London and New York commercial real estate is fanned by the fact that they are “perceived by mainstream investors to be the most likely to deliver strong rental growth in the coming few years,” a Real Capital Analytics report noted.

Like luxury apartments, Manhattan’s top commercial assets attract investors because they are perceived to be liquid and stable.

In terms of pricing, however, New York is not at the top of the heap, which is a positive from an investor standpoint.

That wasn’t always the case: in early 2008, Manhattan was still the second-priciest market for Class A office buildings, behind Hong Kong, measured in terms of yield. Yields are a good measure of Class A office prices because they aren’t affected by exchange rate fluctuations, and because these trophy properties are typically bought in large part for their cash flow.

Class-A office buildings in Manhattan now trade at an average capitalization rate of 4.2 percent, according to Real Capital Analytics. That’s down from its 2010 high of 5.3 percent and well below the national average of around 7 percent. Those rates, which measure return on investment, have been forced down by increasing prices.

However, Hong Kong’s Class A office buildings have by far the lowest average cap rate globally at 2.7 percent, according to RCA, followed by Singapore (3.4 percent) and London (4 percent). Manhattan and Tokyo (4.2 percent) are tied at fourth among major office markets.

In terms of average price per square foot for Class A office buildings, New York, at $1,169, ranks behind Hong Kong ($2,862), Singapore ($2,231) and London ($1,661), but ahead of Tokyo ($918) and Paris ($883).

In terms of average price per square foot for Class A office buildings, New York, at $1,169, ranks behind Hong Kong ($2,862), Singapore ($2,231) and London ($1,661), but ahead of Tokyo ($918) and Paris ($883).

What has changed? For one, the growth in Chinese investment, which has tended to focus on cities close to home, pushing up property prices in Singapore and Hong Kong, explained Colliers International’s Brian Ward, president of the firm’s capital markets and investment services division in the Americas.

Meanwhile, London’s commercial property market benefited from some of the same factors that have driven up luxury apartment prices in that city, such as its favorable location and tax structure.

“New York will be very close behind [in terms of investor demand], but has the disadvantage of not being in that time zone that straddles both Asia and the USA,” said Savills’ Barnes.

Retail realities: New York too strong to be ‘target’ city

When it comes to retail rents, Manhattan and Hong Kong are in a world of their own.

In Hong Kong’s highest-end shopping districts, like the Causeway Bay and Central areas, retail rents average $2,735 and $2,164 annually per square foot, according to a fourth-quarter report from Cushman & Wakefield (the most recent statistics available).

Manhattan’s Upper Fifth Avenue is far ahead of the pack, with a $3,500 per foot average. The most expensive street outside Manhattan or Hong Kong is Paris’ Champs-Elysées, at an average of $1,556 per square foot.

Those prices, of course, influence retailers’ decisions on where to open shop. And retail investment has broader implications for the entire real estate market.

According to Elliman’s Consolo, retail rents are closely tied to luxury housing: the more wealthy people buy apartments in Midtown, the more customers there are for Fifth Avenue’s priciest boutiques. “Retail really marries the rest,” she said.

But while global retailers are flooding into the megacities, retail properties have not become investment vehicles to the same extent that office buildings and luxury apartments have.

While retail condos have become popular in New York, the same is not true for all of New York’s rival gateway cities, Consolo explained.

In some cases, the legal landscape is holding retail investment back. Bertrand De Soultrait, head of retail brokerage at the Manhattan-based Bertwood Realty, explained that French laws make it extremely hard to raise retail rents or get rid of tenants, making retail properties in Paris a less attractive investment play.

London, for its part, was home to the world’s largest retail deal in the first half of 2014: Spanish billionaire Amancio Ortega, founder of fashion retail giant Zara, bought a portfolio of retail properties on Oxford Street for $646.5 million.

But according to Cushman & Wakefield’s latest retail report, New York remains the “focal point” for most national and international retail investment.

Zara parent Inditex also recently bought a roughly 47,000-square-foot retail condo at 503-511 Broadway for $280 million. That comes off the heels of its blockbuster 2011 deal to buy for a $324 million retail condo at 666 Fifth Avenue from Stanley Chera’s Crown Acquisitions, the Carlyle Group and Kushner Companies.

Given Manhattan’s strong retail position, it doesn’t have the same growth potential as other cities. In fact, it does not even feature in CBRE’s ranking of the top 15 target cities for retailers looking to enter new markets, which is led by Tokyo, Singapore and Abu Dhabi.

Still, David Ash of Prince Realty Advisors, who brokered the most recent Inditex deal, said this is hardly a problem. “While pricing has gone up year over year, the demand is still strong,” he said.