On New Year’s Day, Gina Gutloff and her boyfriend were headed out for breakfast when they stepped into the elevator on the 13th floor of their building at 1595 Madison Avenue in East Harlem. As the doors closed, the pair broke into a two-step dance, playfully bopping from side to side, when suddenly, Gutloff recalled, her stomach lurched. The elevator lost power and went dark.

“So I started to panic,” the 25-year-old said in an interview.

Elevators in New York City Housing Authority buildings frequently malfunction, stranding residents and sometimes trapping them inside. In extreme cases, passengers have been killed.

Related | Elevated risk: TRD investigation finds mechanics,

inspectors and landlords falling short on elevator safety

Across the city, elevators are subjected to multilayered inspections, but an investigation by The Real Deal last month documented a broken system that has left thousands of elevators untested, while putting passengers and elevator mechanics in danger.

Our reporting found that chronic mismanagement, a lack of funding and understaffing at NYCHA’s elevator division has left 400,000-plus public housing residents at greater risk of elevator accidents and outages than the general population.

NYCHA has recorded 73 injuries in its elevators since 2013, including seven last year. That means these incidents occurred at a rate of five times more than in other buildings in the city. In that same time frame, there were three elevator-related fatalities in the agency’s buildings.

The state of elevator safety enforcement and maintenance at NYCHA is a symptom of the wider issues afflicting the beleaguered city agency, which is trying to reinvent itself following a damning lawsuit brought by the federal government last year. Among the allegations were startling accounts of elevator maintenance crews dodging penalties from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. This followed comptroller audits, investigative reports and a public outcry over the living conditions at the city’s public housing. NYCHA representatives, however, say the agency has taken steps to make its elevators safer and more reliable.

“We take the safety of our residents very, very seriously and work hard to see that through,” Joey Koch, senior vice president for operations support services, which oversees the elevator division, said in an interview.

TRD spoke with more than a dozen NYCHA residents at three housing complexes, and most said the elevators are regularly broken. At one building, 70 East 108th Street, resident Melissa Rivera said one of the two elevators breaks down at least “four times a month,” and during the summer months, a line of people waiting for the elevator extends outside of her building. At a building in Brooklyn, 177 Sands Street, one of the elevators was out of service when TRD attended, and residents said it had not worked for six days.

“They fix them one week, the next they are broke down,” said Louis Navarro, a 30-year resident.

As Gutloff and her boyfriend tried to remain calm in the darkness of the elevator at their East Harlem building, the Fire Department arrived after 15 minutes and forced open the doors with a crowbar, which revealed they were stuck between the 10th and 11th floors. Gutloff crouched down and jumped forward to the floor after her boyfriend. It was a risky move; if she had lost her balance on the landing, a 100-foot drop down the elevator shaft was behind her.

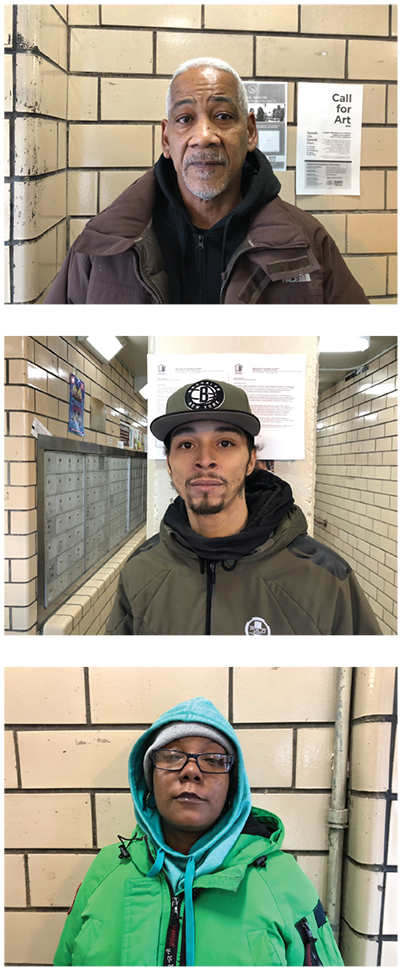

From top: Louis Navarro, 56, Jasper Ferguson, 35, and Kadesha Bremby, 40–all residents of the Farragut Houses n Brooklyn, which had a broken elevator when TRD arrived. The elevator had been broken for six days, they each said.

It was the second time she’d been trapped in the elevator in the two decades she’s called Lehman Village home. In that time, she said, NYCHA maintenance crews have been a rare sight.

“The only time is when someone is stuck in the elevator,” Gutloff said. “Maintenance work is usually around the summertime because that’s when it breaks down the most.”

Ticking boxes

The majority of elevators in New York City — around 63,000 — are maintained and operated by the city’s Department of Buildings, which has jurisdiction over NYCHA elevators. However, the housing authority is responsible for conducting inspections, tests and maintenance of its 3,237 elevators across 2,350 buildings.

Every NYCHA elevator is out of service, on average, at least once each month, the agency acknowledged in a 2018 report. Since 2014, the average time it takes for the agency to resolve elevator outages has nearly doubled, climbing from 5.7 hours to 10 hours in 2018. According to NYCHA, the increase can partly be attributed to paperwork filed with incorrect dates, as well as mechanics doing more thorough checks of the elevators before putting them back in service.

Not only are NYCHA’s elevators often broken, but these breakdowns frequently occur when residents are in the elevators. NYCHA work order data reflects that, in 2016, approximately 1,900 elevator outages involved a passenger who was stuck in the elevator during the outage. It took NYCHA an average of two hours to resolve these situations.

In 2010 and then again in 2015, reports by the city comptroller’s office also found that NYCHA failed to keep thousands of records of preventative maintenance and inspections, including those pertaining to its elevators.

There are two primary reasons that explain the agency’s failures. One is that NYCHA’s elevators require some $1.5 billion in repair and replacement work — just a piece of the $32 billion in capital funding that the agency estimates it needs in total.

Another is that NYCHA only has 10 mechanics to handle annual inspections of its 3,000-plus elevators. According to the agency, another 200 mechanics and 180 helpers (less-skilled workers who assist mechanics) handle day-to-day maintenance and vacate open violations, with each mechanic assigned to roughly 30 elevators.

The overwhelming pressures on mechanics, who receive three days of training per year, has impeded their ability to adequately maintain elevators. The paperwork required to check off a maintenance test is so laborious, many simply fill out the forms without actually conducting a test, according to former mechanics who spoke to TRD.

“You’re stuck in this position: Do I service the paperwork, or the elevator?” said Daniel Ciccarelli, who worked as a mechanic with NYCHA for nine years before he left the agency in 2017.

A culture of ticking boxes instead of guaranteeing safety has been documented in past years, and in one case two mechanics and a senior NYCHA official were criminally charged in November after a fatal incident.

The death of 84-year-old Olegario Pabon occurred on Christmas Eve in 2015 at his building at 2440 Boston Road in the Bronx when the elevator he was stepping into began to drift upwards with the doors open, dragging up his leg and arm. He fell out of the lift, and then died from his injuries three days later.

NYCHA officials didn’t learn of the incident until four days later, and the agency had been alerted to the elevator’s dangers just hours before Pabon entered the car, according to a subsequent Department of Investigation report. The root cause was determined to be a nonfunctioning brake monitor, which shuts down or resets an elevator when the brake isn’t working properly — a hazard investigators identified in 80 other NYCHA elevators across the city. The DOI found that elevator mechanics had likely disconnected the brake monitor in order to prevent shutdowns.

While the incident prompted the demotion of the head of NYCHA’s elevator division, Kenneth Buny, he continued to sign off on inspections and repairs for nearly two years. In 2017, NYCHA appointed a senior deputy director of elevators, David Graham, who is licensed and was able to take over those duties from Buny. However, Ivo Nikolic, who replaced Buny as the elevator division’s director and still holds the position, has yet to be licensed with the DOB. Calls and emails to Buny and Nikolic were not returned.

Of the 14 recommendations made in the 2016 DOI report, NYCHA said it has implemented all of them, which included improving its response to resident complaints and increasing training around brake monitors. Former DOI Commissioner Mark Peters, who authored the report, declined to comment.

But negligent practices within the agency have remained an issue. Even after Pabon’s death, officials continued to sign off on falsified maintenance reports. Starting in 2014, and until June 2018, three senior elevator directors, Derrick Graham (no relation to David Graham), Virgel Fincher and Alan Guadagno, lied on 33 maintenance reports, under pressure to meet paperwork filing requirements, according to indictments unsealed by Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance. The three men could not be reached for comment.

A separate lawsuit filed by federal prosecutors in 2018 documented how elevator maintenance crews had systematically deceived federal auditors. NYCHA inspectors gamed HUD’s annual Public Housing Assessment System inspections by rushing ahead of auditors to make sure no elevators were out of service. Low scores could mean more inspections by HUD, whereas a high score could mean fewer. According to the complaint, NYCHA created “a culture in which staff feel compelled to obtain high PHAS scores, no matter the cost.”

While the federal case centered on widespread vermin infestations, mold and decrepit living conditions for public housing residents, it also revealed that elderly and disabled residents are regularly stranded in their own buildings due to out-of-service elevators.

Several residents of Pabon’s building told TRD on Jan. 17 that one of the elevators constantly breaks down. “They don’t fix it, they patch it, let’s be real,” said Thelma Smith, a 12-year resident. “It functions for a minute, then breaks.”

Private answers?

Elevator safety in NYCHA buildings is pegged to the larger success of the agency. Mayor Bill de Blasio and HUD Secretary Ben Carson have agreed, among other things, to increase federal oversight of NYCHA. Though the city will commit $2.2 billion over the next 10 years, the deal doesn’t cover all of the agency’s funding needs.

Still, officials have taken some steps to change how the agency operates. In November, NYCHA announced plans to turn over the management of 62,000 apartments in the agency’s housing complexes to private companies.

As part of the program, private developers will take over the day-to-day management of those projects, which will be converted to Section 8 housing — a program that provides federal subsidies to landlords in exchange for renting out units to low-income tenants. Landlords, who are collectively required to dedicate billions of dollars to renovating the buildings, will receive rent and federal subsidies in return.

But some of the companies already tapped to take over these properties have drawn criticism for their maintenance of elevators at other properties. Wavecrest, a Queens-based property management firm, is being sued in connection to the death of Stephen Hewett-Brown in December 2015. Hewett-Brown was crushed while trying to escape an elevator that had stalled at 131 Broome Street, a Section 8 housing complex co-owned by the city and the Archdiocese of New York’s Catholic Charities. Wavecrest received $60 million in federal funding in 2012 to renovate the building, including its elevators.

“This was a tragic situation,” said Wavecrest CFO Susan Camerata. “This was not something that was caused by Wavecrest Management.” The DOB said that the official cause of the accident was that the elevator was overloaded at the time.

In January, Wavecrest was part of one of three teams selected to repair and upgrade 1,700 apartments in the Bronx and Brooklyn as part of NYCHA’s Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT) program. The city’s announcement specifically identified heating and elevator upgrades as part of these renovations.

“I think this is one of the only avenues that NYCHA has,” Camerata said. “The deferred maintenance [in public housing] is horrific.”

In December, as part of a plan dubbed NYCHA 2.0, the city vowed to replace 108 elevators in the agency’s buildings over the next three years and then an additional 165 elevators in the next five. But whether this will become a sure sign of improvement to the safety of the agency’s elevators remains to be seen.

Skender Bracellari, who worked as mechanic’s helper with NYCHA for 27 years before leaving the agency in 2013, said the maintenance and safety protocols of the elevator division declined as officials who had no experience with elevators were appointed to lead the division of nearly 400 technicians.

“Failure starts at the top and works its way down,” Bracellari said. “If you have people out there managing who don’t know anything about the trade, how are you going to have a clue?”

—This is the second story in a two-part series on elevator hazards.