It’s a tough time to be a retail broker in Manhattan — especially for those at smaller shops. As the borough’s leasing market continues to slow after its red-hot streak in 2015, fewer deals are being signed. And many of the big leases that make headlines are taking longer to close and are often clocking in at lower rents.

For the majority of brokers, that means less business overall and smaller commissions on each transaction. Meanwhile, the continual proliferation of e-commerce websites and a growing influx of foreign retailers, which often come with different demands and cultural barriers, present their own hurdles.

“There was a time when everyone wanted to be a retail broker because they saw it as an easy way to make a buck,” said Robin Abrams, a principal at the Manhattan-based firm the Lansco Corporation.

Those days are over, she noted, explaining that fewer young people are entering the retail brokerage business because “the market is a bit more challenging.”

Norman Bobrow, founder of the eponymous Manhattan-based commercial brokerage, took it further. “I discourage all brokers in my office to work in retail unless they have an exclusive,” he said. “It is not the place to be in.”

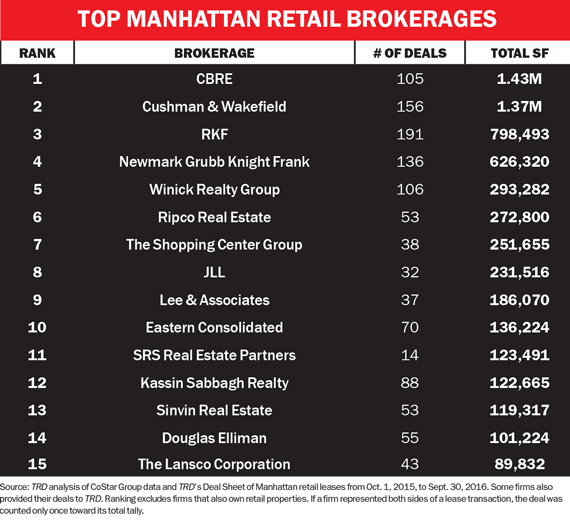

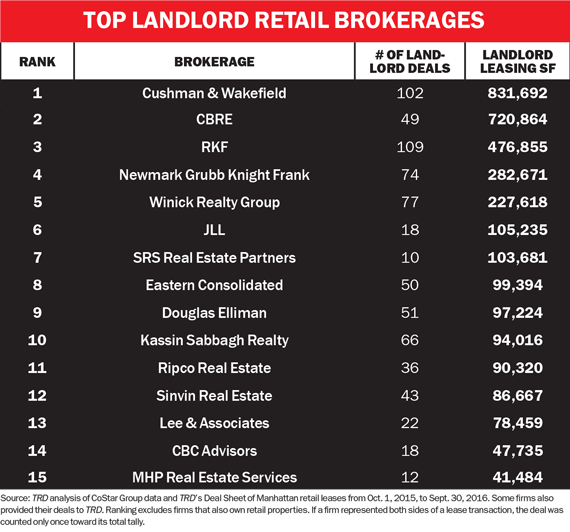

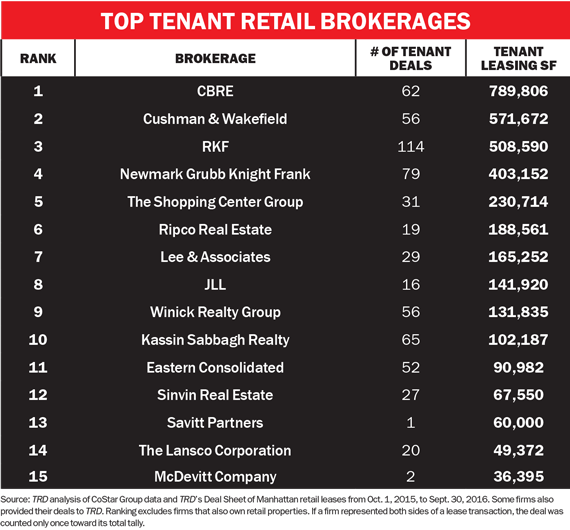

This month, against this worrying backdrop and with the holiday shopping season gearing up, The Real Deal ranked the top 15 firms by the amount of retail space they leased in Manhattan between Oct. 1, 2015, and Sept. 30, 2016.

The numbers, which were gathered using CoStar Group data and TRD’s own monthly deal sheet, as well as information provided by some of the firms, show a significant disparity in how much square footage the top few firms brokered and what the rest of the pack has inked.

Clocking in at No. 1 was CBRE with 1.43 million square feet of both tenant- and landlord-side deals. That firm was closely followed by Cushman & Wakefield with 1.37 million square feet, RKF with 798,493 square feet and Newmark Grubb Knight Frank with 626,320. But after those four heavyweights, there was a steep drop-off.

That’s not to say firms are not doing deals.

“Everybody says they’re extremely busy — that it’s been a very hectic time,” said Abrams, whose firm took the No. 15 spot on the ranking with nearly 90,000 square feet in leasing. “And speaking for myself: We’re doing deals. The deals are more challenging, and therefore they’re taking longer.”

Still, even the optimists admit that the business has become harder and noted that it’s only going to get more intense heading into the new year.

“What you’re going to see as we’re moving into 2017 is that it’s going to become more competitive,” said Cushman & Wakefield’s Gene Spiegelman, who oversees the firm’s North America retail leasing operation.

Necessary evil

A November report by the Real Estate Board of New York confirms that Manhattan’s retail market is cooling after years of frenzied growth.

Between fall 2015 and 2016, average asking rents fell in 11 of Manhattan’s 17 retail submarkets, the report found.

The swath of the Flatiron District on Broadway between 14th and 23rd streets was hardest-hit, with asking rents sinking 23 percent. Meanwhile, asking rents dropped 11 percent in Herald Square as well as on Madison Avenue between 59th and 72nd streets.

The Financial District stood out as the past year’s outlier, with asking rents rising 20 percent as pricey space in new developments such as the World Trade Center mall hit the market.

Overall, tenants have been less willing to sign pricey leases, while landlords have been equally unrelenting when it comes to lowering their asking rents. The result? A tamped-down deal-making environment.

“We’re coming off of many years of big flagship luxury deals,” said Andrew Goldberg, a longtime retail broker and vice chairman at CBRE. “Now there are fewer tenants out there still looking to do those kinds of large transactions.”

Abrams suggested that the correction was a necessary evil.

“Retail rents [in Manhattan] were at all-time highs, and there was a bit of a disconnect,” she said.

The slowdown in leasing activity can be largely traced back to the retail property investment craze seen in recent years, brokers say.

Between the beginning of 2011 and July 2016, investors pumped $25 billion into Manhattan retail properties, data from research firm Real Capital Analytics shows. Many of these deals sold at relatively low capitalization rates, with buyers banking on steep rent growth to make a profit. Lowering rents was certainly not an option, sources say.

“I think the challenge is that in parts of the market that are overpriced, there are many people who purchased buildings over the past few years and then projected rents that were probably too aggressive,” said Jeffrey Roseman, of Newmark Grubb Knight Frank.

On the new development front, the WTC retail complex has in many ways become a symbol of the retail slowdown.

While the Westfield Corporation, the Australian mall operator that developed the mall there, signed on numerous high-profile tenants, such as H&M and Victoria’s Secret, more than 40 percent of the shopping center’s storefronts were closed when it opened in August. It was unclear where that percentage stood last month.

Meanwhile, Westfield has sued several retailers for attempting to back out of their leases.

Still, there are pockets of strength in the market.

Roseman — who recently represented Cinemex, one of the biggest movie theater chains in the world, in a 50,000-square-foot cineplex at 400 East 62nd Street — said he is currently seeing

robust interest in a handful of Soho retail properties he’s marketing.

That, however, is largely because the landlords have owned them for a long time and can afford to ask 30 to 40 percent below what similar spaces in the neighborhood are seeking, he said.

In this sense, the decline in asking rents in prime shopping districts like Soho — where REBNY reported a 9 percent drop on Broadway — can be a good sign.

For starters, some industry observers have voiced concerns of a bubble within the past year, as TRD reported in July. In addition, for many in the brokerage business, it means that deal activity will likely pick up again. The upcoming holiday season will give the retail brokerage industry a clear sign of which way the wind is blowing.

Big fish, small fish

Challenging market dynamics have arguably made the brokers’ role that much more important.

And TRD’s latest ranking illustrates that a stark divide has grown between Manhattan’s leading firms and some of the smaller firms in the mix.

Indeed, the three top firms on the ranking — CBRE, Cushman and RKF — all saw their deal volume jump significantly over TRD’s 2013 ranking, the last one we published. However, some firms didn’t provide their full deal tallies in that ranking, so only deals in CoStar were included. As a result, their numbers may have been slightly lower than their actual totals.

Still, under those same circumstances, several smaller firms, such as Ripco Real Estate (No. 6 on TRD’s ranking this year), SRS Real Estate Partners (No. 11) and Sinvin Real Estate (No. 13) — logged less deal volume this time around. Ripco and Sinvin confirmed their numbers, while SRS declined to comment.

The looming question, however, is why the big firms are getting a large slice of the pie while many smaller players continue to lose market share.

Bobrow argued that big brokerages such as CBRE and Cushman are less vulnerable to market slowdowns because they have an easier time winning exclusives from major national and global retail chains. The key to scoring those assignments, he said, is being able to offer a larger network and a broader range of services.

“If you’re lucky enough to have an exclusive with a major retailer that wants to open up locations, then you’re okay,” he said. “But the mom-and-pop businesses, they are struggling. They’re not opening up additional locations.”

Moreover, Spiegelman argued that large firms are less dependent on the whims of the Manhattan market because they have

offices in other cities and countries, and offer advisory services that extend beyond retail — and beyond brokering altogether.

For example, Cushman & Wakefield — which was acquired by European real estate services firm DTZ’s parent company TPG last year for $2 billion — is “built to withstand” a Manhattan market dip, Spiegelman argued.

Yet while larger brokerages have a competitive advantage, that doesn’t mean smaller firms aren’t winning assignments.

Ripco’s Peter Ripka, Richard Skulnik and Jeffrey Howard, for instance, represented Target in its 29,000-square-foot Hell’s Kitchen lease at Xinyuan Real Estate’s 615 10th Avenue last month. Xinyaun was represented by Brandon Eisenman and Thomas Cholnoky at RKF.

Lansco’s Abrams said she believes smaller firms still have a good shot at competing with larger rivals.

“I do think there are often shakeouts in areas where a tenant may not get the results they want and will start looking for firms that are more hands-on,” she said.

“Some business we are never going to get, some business we can win all day long,” she added.

Silver linings

Despite the current challenges in Manhattan’s retail market, a slowdown is not the same as a crash. And 2016 has certainly seen its share of high-profile deals.

In February, for instance, Coach signed a lease at Thor Equities and General Growth Properties’ 685 Fifth Avenue with a rent of $4,000 per square foot on the ground-floor portion. But sources say that number does not factor in concessions thrown in by the landlords, such as paying for build-outs.

And in another major deal, Nordstrom signed a 43,000-square-foot lease at SL Green Realty and Moinian Group’s 3 Columbus Circle last January. Derek Trulson of JLL, which ranked No. 8, and Stephen Stephanou of Crown Retail Services represented Nordstrom in that deal. Jeff Winick of the No. 5-ranked Winick Realty Group represented the landlords.

Nonetheless, brokers say that getting deals done takes longer than it did just a year or two ago.

“The process overall takes longer from start to finish,” reiterated Abrams, whose team is currently working with the U.K.-based fashion retailer the White Company in its hunt for a New York location. Abrams said the company — which is nearing a deal — had been eyeing the Big Apple for a while but only recently grew more comfortable with pricing here.

Some retailers have simply not found their comfort zone and have opted out of the New York market altogether.

Bobrow said he recently represented an art gallery that had opened a pop-up store and wanted to transition into a long-term lease. But the landlord refused to lower the asking rent to a number the gallery could swallow, so that deal failed to come together.

NGKF’s Roseman said retail tenants have become both more cautious and more demanding.

“Every deal I’ve worked on in the past year or two has sort of slowed,” he said. “Years ago a retailer would see a store and say, ‘I want to make a deal here.’”

Today they are far more systematic about finding the right location. That’s partly because many of them are owned by

private-equity firms with multiple stakeholders involved in leasing decisions, Roseman explained.

“The stakes are higher now,” he said. “Rents are [more expensive], and retailers can’t afford to make mistakes.”

The e-commerce effect

The slowdown in New York retail leasing and the heightened competition among retail brokerages aren’t entirely cyclical. Sources say they are also the result of online retail’s continual rise. Shopping centers and mid-market retailers have been particularly hard-hit.

It’s no secret that major retailers are scaling back.

In June, Ralph Lauren said it would cut 8 percent of its workforce in the 2016 fiscal year. Macy’s and Nordstrom also announced store closures earlier this year, while Aéropostale shuttered its Times Square flagship store in May. These cutbacks in brick-and-mortar retail are one of the big reasons there are fewer big deals for brokers to close.

“People are going out of business left and right,” said Bobrow. “It’s a much smaller market, and it became much harder to rent retail space.”

At the same time, several e-commerce upstarts are looking to open flagship stores in New York.

Amazon, for one, is planning its first Manhattan store at the Related Companies and Oxford Properties Group’s Hudson Yards, according to the New York Post.

Online clothing retailer Bonobos, meanwhile, has signed leases in NoMad and at Brookfield Place.

But for brokers, working with online retailers means adapting to a new way of doing business, which can add another challenge.

NGKF’s Roseman said he recently brokered a 3,700-square-foot lease at 30 West 15th Street on behalf of Rent a Runway — an online firm that rents out designer dresses.

“(Tech startups are) probably a little bit less weathered and experienced,” he said. “But that doesn’t make them any less intelligent.”

Abrams said working with online retailers can have its perks.

“If they have an established online business, that’s a really great tool because they have all that data on who their customer is,” she said.

Firms like Amazon, for example, can go through their sales data to find out exactly which neighborhoods they are popular in, and plan their bricks-and-mortar strategy accordingly.

“We’re going through a structural change where tech is leading the way and real estate is adapting,” said Spiegelman.

Revolving doors

With the industry in a state of flux, a number of high-profile brokers have been jumping ship.

Although brokerage executives say the turnover isn’t unusual, it is having a ripple effect during a difficult time in the market.

Early last month, two high-producing Cushman brokers, David Green and Bradley Mendelson, who have worked on deals involving the likes of the Gap, Anthropologie,

Uniqlo and many other brand names — jumped to Colliers International.

Former Cushman director Corey Horowitz, meanwhile, left the firm just a few months earlier to become a principal at Lee & Associates.

Cushman has made some gains, however.

About a year ago, it snagged Winick Realty’s Diana Boutross, who had brokered Whole Foods’ Williamsburg lease among other big deals. And, of course, outside of retail on the investment sales front, it recently scored the coup of the year when it lured over Doug Harmon and Adam Spies from Eastdil Secured.

Still, according to Joel Herkowitz, the COO of Lee & Associates, the bureaucracy at larger firms can be a headache for some agents.

“There are people who feel disenfranchised, lost, who feel they’re competing with brokers in their own firm rather than against other firms,” he said.

Herskowitz, who spoke to TRD early last month, said he had interviewed three candidates for agent positions that day — two of them senior professionals.

In general, retail brokerage executives said they’re not cutting brokers but are expanding more cautiously.

“I know we have upped our barrier of entry,” said NGKF’s Roseman. “We’re not just looking to fill desks by any means.”

Meanwhile, several other firms, most notably Douglas Elliman and Lansco, have seen shake-ups.

Elliman’s retail team, headed up by Faith Hope Consolo, recently saw the dramatic departure of Joe Aquino. Aquino, who had been Consolo’s right-hand man, sued the company for allegedly using his commissions to pay for Consolo’s personal expenses. A judge dismissed the lawsuit in October. The firm ranked No. 14 with 55 deals totaling 101,224 square feet.

And Lansco suffered a big blow last month when two brokers (Matt Cohen and Peter Weisman) as well as three of the firm’s five vice chairs — Jack Walis, Jerome Ginsberg and Mike Antkies — quit.

“A few of the partners have not been active recently and felt it was time to cash out,” company CEO Stuart Lilien told TRD last month in response to the departures. “It won’t affect our business.”

But before that news broke, Abrams, one of two remaining vice chairs there, said the firm had been “discussing downsizing” but actually has hired a few seasoned brokers recently.

For his part, Ripka, founder of Ripco, told TRD he’s hired three young agents in the firm’s Manhattan office over the past year.

“Training young people takes time, that’s the con. The pro is, they work within your way of work and weren’t jaded by another organization,” he said.

Last year, the firm increased its Manhattan footprint by 2,500 square feet to more than 10,000 square feet with an eye on increasing its head count. Although he said the market is competitive today, he added it’s in far better shape than it was a few years back. “I feel a million times better now than I felt in 2008,” he said.