It was a telling moment for those fixated on Opportunity Zones.

“Who the hell is EJF and their expertise as it relates to real estate?” Anthony Scaramucci asked on a December conference call to promote his $3 billion Opportunity Zone fund.

The rhetorical question seemed to be an attempt to reassure potential investors that EJF Capital would be a qualified partner for Scaramucci’s firm, SkyBridge Capital. But the former White House communications director’s swagger wasn’t enough to move the needle — and the two hedge funds parted ways a month later.

SkyBridge attributed the split to concerns from its distribution partners that EJF didn’t have enough experience managing real estate funds. “It’s a difficult investment environment,” the firm’s president, Brett Messing, told The Real Deal. “People get more risk-averse. And being risk-averse means bringing your clients a track record and someone who might be a little more known for being associated with real estate.”

The quest for another OZ partner was short-lived: SkyBridge announced in late January that it had teamed up with the property investment firm Westport Capital Partners. But its split with EJF was one several signs that OZs are a less straightforward investment opportunity than originally thought.

Companies that launched funds in New York are still figuring out the best ways to raise capital and when and where to deploy it. And despite the program’s goal of revitalizing downtrodden parts of the country by providing tax breaks for those who pour money into new developments, some of the city’s OZs are located in relatively posh neighborhoods with projects from sponsors better known for luxury skyscrapers than affordable housing.

Since being shoehorned into the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, OZs have faced multiple challenges — from a fragmented fundraising landscape to the record-long government shutdown. The political standoff has slowed the overall process, delaying several key guidelines and canceling an Internal Revenue Service hearing last month intended to focus on tax breaks and proposed regulations.

That has created an environment where a growing number of people are realizing how much they still don’t know about OZs. Roughly half a dozen New York real estate players have announced plans within the past year to set up related funds, with most looking to raise between $100 million and $500 million. But while firms across the board are thrilled about the program’s potential, virtually none can say exactly how it will all work out.

“There are still a lot of questions,” said Bryan Woo of Manhattan-based developer Youngwoo & Associates, whose firm launched a $500 million OZ fund with the real estate crowdfunding startup EquityMultiple. “It just becomes that much harder to have a serious conversation with an investor, because that investor is going to want some kind of legal guidance.”

Many are scrambling to fill that information vacuum — dozens of law firms with tax or real estate practices have issued white papers detailing potential regulations, commercial brokers are frantically searching for opportune sites, and fund managers are seeking out investors by the thousands.

“There’s lots of speculation out there, a lot of which is not fully accurate,” said Steve Glickman, a former senior economic adviser to President Barack Obama and one of the architects of the OZ program. “Some of those voices are well-informed. But many are not and are just trying to create a brand for themselves in the space.”

The New York route

A total of 8,762 census tracts across the country have been designated as OZs. That includes 514 in New York State — 306 of which are located in the five boroughs, per data from the Urban Institute and New York’s Empire State Development Corporation.

The process of identifying what parts of the city could be classified as OZs began in February 2018, when the federal government gave Empire State Development more than 2,000 tracts it had identified as “low-income.”

New York officials then had just 90 days to cull through those areas and recommend about 25 percent to be included in the program, according to sources familiar with the rollout. They quickly removed areas that appeared to have been accidentally included — one encompassed Central Park — and went to Regional Economic Development Councils to get more local expertise on which tracts would be an ideal fit for the program.

State officials tried to include areas where they were looking to increase investment and where they projected the most investment interest would arrive. These areas included the South Bronx, East Harlem, the Rockaways and Crown Heights — along with tracts in less-expected neighborhoods like the Far West Side and the Lower East Side.

Helping select the census tracts should put an end to the state’s involvement, as the IRS will run the remainder of the federal program, sources said. But the agency was facing delays implementing rules and regulations even prior to the prolonged government shutdown, and interruptions seem likely to continue. As a result, many federal requirements for the OZ program are still not finalized, hampering the amount of momentum that can build up in the market.

“A lot of people are interested, but no one knows how the mechanics are going to work,” one source in New York state government said on condition of anonymity. “It’s very difficult because they keep saying they don’t want to put in too many regulations.”

Census tracts designated as OZs in Bushwick and Far Rockaway saw the most activity across new building permits in 2018, with plans for 51 projects filed in each neighborhood, according to a TRD analysis of city records. Projects in Long Island City and the surrounding area came next with 45, followed by Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant with 36 and Ocean Hill with 33.

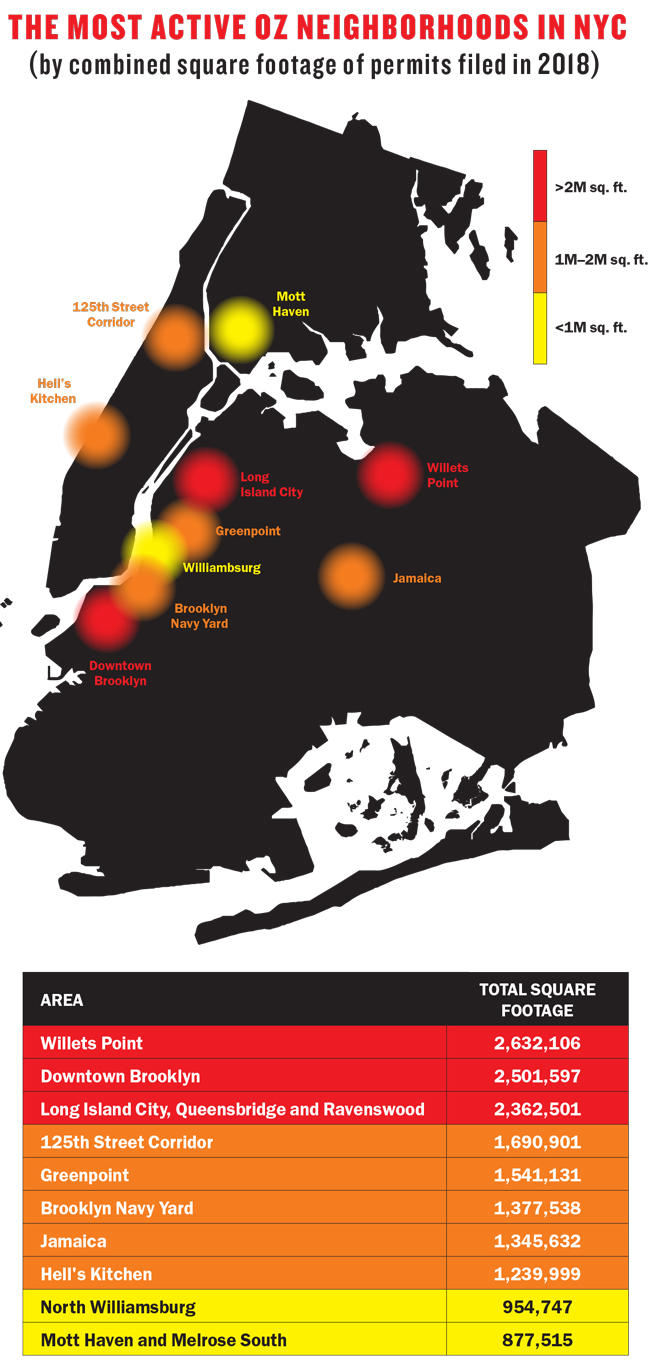

OZs in Willets Point, Queens, saw the most activity by total square feet among permits filed last year at about 2.6 million, followed by Downtown Brooklyn (2.5 million), the LIC area (2.4 million), Manhattan’s 125th Street corridor (1.7 million) and Greenpoint (1.6 million).

Queens-based developer F&T Group has the highest concentration of square feet being built in OZs, roughly 1.4 million, thanks to its massive Tangram project in Flushing. F&T was followed by the Durst Organization (1.2 million) and TF Cornerstone (998,000).

Durst made that list largely due to its Queens Plaza Park project on Northern Boulevard. But company spokesman Jordan Barowitz said the 63-story mixed-use rental tower had been in the works long before the OZ program came to light and that the project was never altered.

The family-run real estate firm examined the OZ program when it launched and ultimately decided it was not a good fit for the way the company does business, Barowitz noted.

“We don’t put together funds to purchase our development sites, nor do we sell our projects,” he said.

Queens Plaza Park was the second-largest project in a New York OZ, behind TF Cornerstone’s mixed-use rental tower the Max at 606 West 57th Street. The development firm, which declined to comment, also began its project before the program was announced, and the 44-story tower near Billionaires’ Row is far from one that most would associate with a struggling part of the city — rental prices run as high as $8,000-plus a month.

The Max is located in Census Tract 135, which runs from 10th Avenue to the Hudson River and from West 50th to West 58th streets. The U.S. Treasury Department, led by native New Yorker and former investment banker Steven Mnuchin, identified the area as a low-income tract, and the New York City Regional Economic Development Council recommended it as an OZ based on city investments, sources said.

A mixed bag

Jim Costello, senior vice president at the real estate data provider Real Capital Analytics, said states were given flexibility in how they define OZs and that time will tell whether the strategy of including a mix of higher-income and lower-income areas makes sense.

He said RCA has seen the largest increases in sales volumes in areas showing signs of gentrification.

TRD’s data analysis in New York supported that, with the most active OZ neighborhoods by total dollar volume of sales in 2018 including Gowanus, Washington Heights and Mott Haven. The total dollar volume of property sales in the top 20 OZ neighborhoods in the city was about $10.7 billion last year.

“I think 10 years from now, we’ll see which approach worked best,” Costello said. “Did it work best to focus on only the poorest areas of one state or concentrate it all on one city? Or to include some high-income areas in between low-income areas in places like New York? There’s rationales for all of them.”

Brett Theodos, a research associate at the Urban Institute’s Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center, was more skeptical that designating areas already seeing signs of improvement is worthwhile.

Jamaica

“I’m confident those areas will attract investment,” he said. “But first, will that investment benefit low- and moderate-income residents, and second, will it be worth our public money to do so, or would those areas have gotten plenty of investment on their own?”

An Urban Institute analysis found that 21 percent of tracts designated as OZs in New York City had already experienced “sizable socioeconomic change,” which it defined using factors such as rising family income and an increased number of residents with a bachelor’s degree or higher between 2000 and 2016. This percentage of change was even higher in cities like Seattle (40 percent), Oakland (37 percent) and Washington, D.C. (32 percent).

Costello described the overall process of identifying OZs as “very rushed.” “The implementation was pushed to the states with little head start for them to figure that out,” he said.

One government source attributed the program’s bumpy debut to its inclusion in the 2017 tax law. “Everybody was surprised this was in the tax bill — including the IRS and the Treasury,” the source said. “They did not know about it.”

Capital gains

Despite lingering uncertainties surrounding the program, fundraising for OZs has already begun in earnest in New York.

Developers are mainly targeting high-net-worth individuals, and the investments need to be finalized by the end of the year in order to take full advantage of the 15 percent discount the program includes on capital gains taxes. That deferment ends on Dec. 31, 2026, and investors need to have property in an OZ for at least seven years to get the full discount.

In addition to OZ funds from SkyBridge and Youngwoo, other planned investments in the city include a $500 million fund from RXR Realty, a $250 million fund from Normandy Real Estate and a $100 million fund from Toby Moskovits’ Heritage Equity Partners.

Woo said his team is mainly focused on acquiring assets in northern Manhattan and the South Bronx. One of the recent challenges, he said, is that all the hype around OZs has caused some prospective sellers to view their properties as more valuable than they actually are.

Sellers seeking higher prices are not entirely out of line, as RCA found that sales of development sites in OZs across the country spiked 80 percent during the first three quarters of 2018. Woo acknowledged there can be a premium on assets in some designated areas but stressed that the same standard should not apply to every property.

“It’s not the same within neighborhoods [or] within zones,” he said. “It’s not the same building to building.”

Heritage Equity has some of its most notable projects in neighborhoods like Crown Heights and Sunset Park, which Moskovits pointed to as evidence that her fund is “a quintessential Opportunity Zone developer.” The fund is also focused on acquiring sites and making sure they are ready to start building on them as quickly as possible.

Moskovits maintained that all of the city’s outer boroughs have room for more housing and views the OZ program as a great way to take advantage of that. “We started with the piece we think is most critical,” she said. “And that’s identifying the transaction, getting sites under contract and getting them shovel-ready.”

RXR is mostly focused on raising capital from high-net-worth individuals via wealth management firms and alternative investment arms at major banks, its President and CFO Michael Maturo said.

He noted that RXR already has a pipeline of assets in areas that have been designated as OZs, so it does not need to focus as much on acquiring properties. The firm had been working on a similar initiative before the federal program launched, so Maturo said RXR was ready to take advantage once it did. “We formed a fund in 2015 called the emerging submarket fund,” he recalled. “Its purpose was to invest in areas outside Manhattan.”

RXR now plans to use the OZ program to further develop its projects in areas outside the city, including Yonkers and New Rochelle. “Those are areas that have good connectivity to transit but have been underinvested for many years,” Maturo said. “This is going to be a natural segue to extend development in those areas.”

Fundraising is also the top priority at Normandy, according to its founder and partner Jeff Gronning. The company is actively marketing its investment fund, which so far has had the most interest come from high-net-worth individuals.

“We are spending most of our time speaking with investors that have the ability to control the timing of their gains,” Gronning said. “We’re anticipating creating a portfolio of Opportunity Zone investments that will be identified and closed over a two- to three-year period.”

Woo cited three main factors for qualified OZ investors: a track record of investing in real estate, development experience and familiarity with local markets where funds are looking to invest.

“Some of the Opportunity Zones are emerging neighborhoods,” he said. “You have to understand how to speak with local stakeholders within the neighborhood and make sure ultimately that you’re building something that people locally want.”

Pies in the sky?

Messing insisted that SkyBridge is still on track to raise $3 billion — a stratospheric sum compared to how much other OZ funds are looking to raise. “I’ve never been associated with a product that is so easy to generate interest in,” he said.

In a recent Bloomberg interview, however, Scaramucci said his firm had raised $10 million for its fund so far and expects to raise between $500 million and $1 billion this year.

Troy Merkel, a senior real estate analyst at the consulting firm RSM, said he was skeptical about SkyBridge’s investment target.

“I just think it’s hard to deploy that much capital in what’s going to be a relatively tight timeline by one group,” he said. “That’s why I think you’re seeing more of the $250 to $500 million fund levels. I think those are more realistic capital outlays for groups to deploy.”

A number of OZ fund managers, meanwhile, are going to have to reach outside their comfort zones to fill their coffers. Many of their institutional partners — including pension funds and endowments — are already exempt from capital gains taxes, which explains the turn to wealthy families and individuals.

“We have historically raised a very small percentage of our equity from high-net-worth investors, who are likely the biggest beneficiaries of the Opportunity Zone program,” said one anonymous executive at a major real estate private equity firm.

“Like a lot of our peers, it’s our view that the best way to tap into that world is through one of the big Wall Street brokerages: Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, UBS, Bank of America,” the executive added. “We are having conversations with those groups in hopes of basically pushing our offerings to their high-net-worth clients.”

Those middlemen with access to ultra-rich private investors are key figures in the fundraising ecosystem.

The conference organizer Information Management Network is hosting an OZ forum in March at the Union League Club in Manhattan. The list of registered attendees includes executives from Bank of America Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley’s wealth management divisions, as well as several family offices.

One registered attendee, the Hayman Family Office, manages the wealth of late retail magnate Fred Hayman, who founded Giorgio Beverly Hills — the first luxury boutique on Rodeo Drive. DJ Van Keuren, a vice president at the office, said families that spent generations building wealth from businesses that had nothing to do with real estate could be reluctant to write big checks to OZ fund managers they’re meeting for the first time.

“Families like control,” he told TRD, adding that he gets about five emails a day for potential OZ investments. “When family offices are going to invest, they’re going to start with a small check size. Because unlike institutional investors — which are not emotional, because it’s not their money — this is their money.”

In an effort to find the right fit, many OZ fund managers are working with brokers, according to several sources familiar with the matter.

“The high-net-worth and ultra-high-net-worth investors are just less easy to access and less transparent,” said Glickman, who recently launched his own OZ consulting firm, Develop Advisors. “You have to have a pretty good network or work with wealth managers that have a large network of high-net-worth investors that can put money into the program.”

The general lack of experience with these types of investments among high-net-worth individuals can be one of the biggest challenges for OZ fund managers, RSM’s Merkel said.

“They have to educate a lot of the investors about real estate investing in general, because those investors are coming to it with a tax strategy and what they believe is a solid investment plan,” he said. “But they may not have been real estate people.”

Scattered fundraising

There’s another reason that some of the biggest names in private equity may be steering clear of Opportunity Zones: Firms like the Blackstone Group, Apollo Global Management and KKR typically look for deals on a much larger scale than OZs can offer.

Blackstone recently raised a record $20 billion real estate fund that would be extremely difficult to put to work at a scale of a few hundred million dollars or less at a time. Many of the big buyout giants eyeing deals on that scale are usually looking for the kinds of returns that come from developing a property and selling it off once complete. Those timelines may be incompatible with OZ investments of roughly five to 10 years.

Craig Bernstein, co-founder of OPZ Capital, a private equity firm solely focused on OZs, said the market remains fragmented when it comes to fundraising. Bernstein, who previously spent more than a decade at the Maryland-based real estate firm White Star Investments, said he’s targeting investments in New York, Florida, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., focused primarily on multifamily, student housing and self-storage projects.

He said that as things shake out with the OZ program, there will only be enough room for a few big winners. “I think the top 10 percent of [fund] managers are going to be raising the top 90 percent of capital,” Bernstein said.

Some have compared investing in OZs to the problem-plagued EB-5 program, both of which are heavily focused on property development. The Urban Institute’s Theodos said he sees similarities between the two programs — including the lack of a cap and little transparency about where investments will go. There is, however, one notable difference.

“EB-5, for all of its flaws, isn’t actually costing us any money,” he said. “It is bringing new investment, whereas Opportunity Zones are going to cost us a lot of money.”

One of the biggest questions for real estate players is whether OZs will ultimately prove as beneficial as advertised. Several sources familiar with the program cautioned that despite seemingly sound fundamentals, firms shouldn’t view the program as a panacea for all the challenges the industry faces.

“This program is not all of a sudden making infeasible real estate deals feasible,” said Michael Alperin, acquisitions director at the residential development firm Beacon Communities. “It’s taking deals that were close to being developed or about to be developed and making them work. I think there’s probably been a little bit of overhype in the marketplace.”

John Balboni, a real estate partner at the Boston-based law firm Sullivan & Worcester, echoed that point. “Not every real estate deal is a winner just because you’re in an Opportunity Zone,” he said.

The D.C. slowdown

While it seemed investors would burst full steam ahead on OZ projects heading into 2019, developments have been slow. That’s partly due to the U.S. government shutdown that began on Dec. 22 and ended — for at least three weeks — on Jan. 25.

Following the shutdown, “it will take the government probably six weeks to [reach] its full capability,” said Marcus Mason, a senior partner at the Madison Group, a D.C.-based public affairs firm that has lobbied on OZs for Los Angeles County.

The dysfunction in the nation’s capital has thrown cold water on the program’s progress, according to multiple sources.

As of December 2018, CoStar tracked the formation of more than 180 OZ funds targeting a combined $19.97 billion in investments. About a third of those funds were announced in the last few months of the year, when interested parties began reaching out to the IRS and Treasury Department regarding proposed regulations.

A handful of real estate trade groups have weighed in with suggestions on how to tweak the program for their members’ benefit. The industry is looking for clarity on several issues such as the IRS’ 31-month working capital safe harbor rule for funds that are set aside for projects but not technically invested.

Groups like the National Association of Homebuilders and the Shopping Center Group want the IRS to relax the 31-month timeline to allow for factors such as unexpected construction delays.

Others, including the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts, want flexibility on the fixed period that investors have to defer gains into a qualified fund.

As the rules are currently written, investors have to defer their gains within 180 days after the gain would be recognized for federal tax purposes. But NAREIT and others argue that investors often don’t know how their gains will be treated until the tax year ends. The group wants the IRS to delay the start of the 180-day period to the end of each taxable year.

Investors looking to maximize the economic benefits aren’t the only ones pushing their agenda. Others are calling for more regulations. The National Housing Conference submitted comments seeking more reporting requirements “to avoid the potential for fraud and displacement that would ultimately increase the cost of the initiative and turn [OZs] into a costly

tax shelter.”

Glickman noted that the delayed regulations have affected fundraising.

“I think that capital raising has gone slower than some people anticipated,” he said, adding that he expects more momentum once the final round of regulations comes out. “The intermediaries — the wealth managers, accountants, lawyers and others — have put heavier brakes on getting their money into the marketplace awaiting more regulatory clarities.”

RCA’s Costello said investors getting locked into lengthy deals in neighborhoods that may not be as stable as they’re used to means pouring money into OZs could be a risky endeavor.

“There’s a potential capital gain,” he said. “You have to change your behavior to be able to access that gain in terms of not being able to trade out for a certain period of time. There’s extra uncertainty that goes with that, but that’s part of the deal.”

—Additional reporting by David Jeans