If anyone knows what it’s like to be Blake Hutcheson, the CEO of Oxford Properties Group, it’s probably his counterpart at Ivanhoe Cambridge.

Hutcheson and Ivanhoe’s Daniel Fournier are responsible for investing in real estate for two of Canada’s biggest pension funds, which between them manage assets worth more than $300 billion.

With such massive balance sheets, Fournier said, investment banks and brokers always assume they’re looking for low-risk, core assets.

But that’s not a luxury either of them has.

“If Blake and I had done that with our responsibilities in Canada, believe me, we wouldn’t be sitting here today,” Fournier said during a panel last year at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in the Time Warner Center. “We would have been fired a long time ago.”

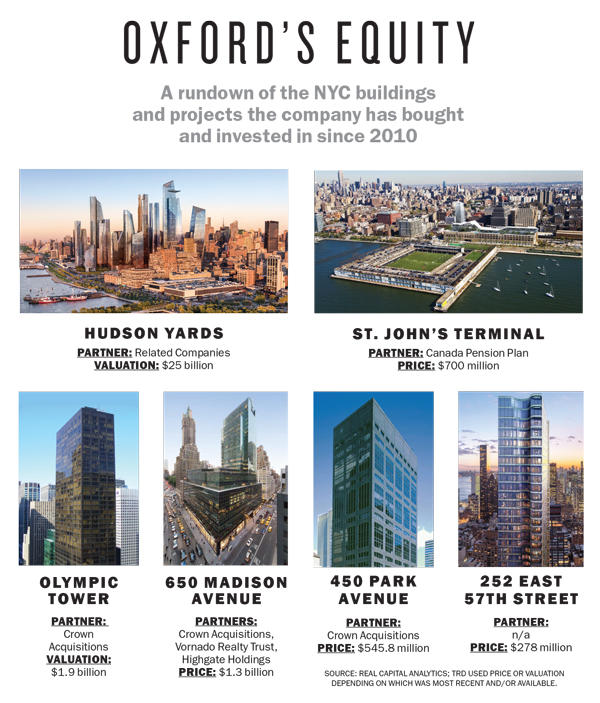

Instead they’ve both had to get their hands dirty with development. In New York, Oxford is best known for partnering with Related Companies on Hudson Yards, the $25 billion megadevelopment that’s transforming Manhattan’s Far West Side. But while the company provided some serious financial muscle on that deal, Related has led the development charge and been the face of the project.

Oxford is, however, done taking a backseat role. While Hutcheson was sitting onstage at the Mandarin Oriental, his company was finalizing a deal to helm its first development project in Manhattan.

Just days before, it had signed a contract to buy the southern portion of the massive St. John’s Terminal building straddling the border of Greenwich Village and Hudson Square for $700 million.

But that project coincides with a leadership shakeup at Oxford, both at its headquarters in Toronto and in New York.

Hutcheson, who took the reins in 2010, is leaving to head up Oxford’s sole shareholder: the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, or OMERS. And another top executive — one of two who launched Oxford’s New York operation — is decamping for another company altogether.

Hutcheson, who took the reins in 2010, is leaving to head up Oxford’s sole shareholder: the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, or OMERS. And another top executive — one of two who launched Oxford’s New York operation — is decamping for another company altogether.

In addition, OMERS is still trying to close a nine-year-old funding deficit thanks to the financial crisis. And it’s doing that by shifting more of its investments into real estate — which, while a vote of confidence in the market, ratchets up the pressure on Oxford. In other words, the pensions of some 470,000 municipal employees in Canada are counting on Oxford to land them strong returns.

Unlike most other real estate players, pension funds have very specific breakdowns of how much money they need to pay out years into the future.

And those demands are on the rise as the population grays. So OMERS knows it needs more cash to keep up with its growing payouts. As a result, Oxford will need to deploy more capital into the real estate market and get bigger, explained Byron Carlock, a partner in the national real estate practice at PricewaterhouseCoopers.

“The old-style pension plans that create a demographic of aging pensioners, but also younger workers contributing to those plans, is much more robust in places like Canada,” Carlock said.

And that, he added, has a significant impact on real estate.

“When big plans like that change their allocations, it really does move the needle in the international investment community for real estate,” he said.

From $0 to $12.8B

As Michael Turner — the Oxford exec tapped to succeed Hutcheson — tells it, the firm could not have done the St. John’s deal five years ago.

“We wouldn’t have had the ability to either do this or have the confidence [back then],” he said during a sit-down on the ninth floor of company’s Park Avenue offices last month. “But we can today.”

But since teaming up with Related, it’s been building out its shop in New York.

For example, Oxford’s headquarters at 450 Park Avenue are located in one of three Manhattan office buildings the company has snapped up with Crown Acquisitions since 2012.

When Oxford teamed up with Related to bid for Hudson Yards in 2010, the company’s New York real estate portfolio was valued at $0. Today it clocks in $12.8 billion, according to Real Capital Analytics.

Turner, who is based in Toronto and will oversee Oxford’s global platform, said Hudson Yards was something of a master’s course in New York development.

“If you rewind the clock to when we opened this office in 2008, we had two guys and a backpack and an idea and a dream,” he said. “[We] got to build out that execution capability at a time when you could make more mistakes, but it didn’t really cost you as much.”

Those two guys were Neil Jacob, the Boston-based head of Oxford’s U.S. operations, and Andrew Trickett, a former vice president for investments at Deutsche Bank.

But the St. John’s acquisition will be Trickett’s swan song with Oxford. He’s leaving to oversee the U.S. investment platform for the Dubai investment firm Safanad.

He’ll be replaced by Kevin Egan, who runs Oxford’s debt business, which has grown substantially in Manhattan in the last eight years. It holds mezzanine positions in properties like the Crown Building, where an unidentified buyer is in contract to buy a penthouse for a record-shattering $180 million.

The others on Oxford’s bench include Dean Shapiro, a CBRE veteran, who will oversee operations in New York, and former Boston Properties exec Adam Frazier, who heads leasing.

Shapiro said Oxford is still looking to fill several key positions as it prepares to break ground on St. John’s.

“We have a lot of resources here now,” he said. “But as we continue to grow, I think we’ll continue to hire and build out sort of a proper development platform.”

Redeveloping Fort Knox

Covering three city blocks, St. John’s is a hulky building that once served as a train terminal for the High Line — back when the High Line was still a functioning railroad, not the high-end park it is today.

Longtime investors Eugene Grant and Lionel Bauman had resisted selling for years.

Finally, in 2006, Grant bought out Bauman and brought in Westbrook Partners, Fortress Investment Group and Atlas Capital Group. Six years later, the investors bought out Grant’s remaining 50.1 percent stake.

10 Hudson Yards, part of the megaproject Oxford

is backing

Real estate attorney Joshua Stein, who represented Grant when he sold his remaining stake in 2012, said that for a long time, much of the property was used as office space for companies like Bloomberg and Verizon.

Grant, who died last month at age 89, “bought it for nothing in the ’60s,” Stein said. “It’s this magnificent potential development site. The thing is built like Fort Knox because of the need to support all of those freight cars.”

After buying out Grant, the investment trio got to work on an ambitious redevelopment plan, which included a rezoning and transfer of air rights from across the street at Pier 40 on the Hudson River. The transaction almost fell apart when news broke that Atlas had struck a secret deal with state lawmakers to buy the air rights — a move that would have circumvented local officials.

“It was very contentious and controversial,” said Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, referring to the community opposition. Local groups were pushing for more affordable apartments and restrictions on certain types of retail, but knew that even without a rezoning the developers could build a massive project as-of-right.

In 2015, Westbrook paid $200 million to buy out Fortress in a deal that valued the property at $650 million. And the following year, lawmakers agreed to green-light the development and grant a rezoning.

In the meantime, Westbrook and Atlas were hunting for an investment partner to pump another $100 million of equity into the project.

Potential suitors — including Brookfield Property Partners, Vornado Realty Trust and RXR Realty — came calling. But Westbrook and Atlas sold the southern portion of the site to Oxford.

Sources close to the deal said Westbrook selected Oxford because it thought the developer would make the project a higher priority than the other bidders.

Westbrook founder and CEO Paul Kazilionis said he was impressed by Oxford’s “excellent track record at Hudson Yards” as well as its “collaborative ethos.”

And Westbrook and Atlas have a lot riding on Oxford’s success, given that they are developing the northern portion of the site — bringing in 593 residential units and 40,000 square feet of retail.

Instead of going with the mixed-use residential and hotel plan approved by the city, Oxford is developing 1.3 million square feet of office (with some ground-floor retail) that was available as-of-right.

Oxford will take off the top floor of the four-story building and construct eight or nine new floors above it. The project’s key selling point will be floor plates as large as 100,000 square feet.

“We think there’s a big appetite for large floor plates and a dearth of them in New York,” Shapiro said.

A leasing team at CBRE is currently talking to potential tenants, but the project faces some headwinds, namely a large supply of new office product coming online over the next two years and a cooling leasing market.

Joe Harbert, president of the eastern region for Colliers International, said finding tenants that want such large spaces could be tricky.

“Large floor plates can be an advantage, but sometimes they can be a hard sell,” he said. “Not everybody’s looking to be on a 100,000-square-foot floor.”

Still, he said there’s demand for a project like St. John’s on the trendy West Side — it’s just a matter of how much tenants will be willing to pay.

“You don’t need all the tenants in the world to like your building, you only need a few,” he said.

Running in the red

While Oxford is owned by OMERS today, it didn’t start out that way.

The firm, which was founded as a real estate company in 1960, went through several iterations as a public and private company before OMERS bought it and took it private again in 2003.

But the last decade has been a tough one for OMERS.

Deficits started mounting during the financial crisis in 2008. In 2012, it hit a low and was only able to meet 88 percent of its payout obligations, a shortfall it’s filled by raising members’ contribution rates.

The pension plan had a $5.4 billion deficit at the end of last year. It’s now pushing to be fully funded by 2025.

And that’s where its real estate strategy comes into play.

When Hutcheson became CEO in 2010, he set a goal of doubling assets from about $16 billion to roughly $30 billion. The company now has a global portfolio valued at $40 billion, but to get there it’s had to look beyond Canada’s borders.

And as it wraps up the first phase of Hudson Yards, Oxford seems to be doubling down on New York.

In February, the company paid nearly $280 million to buy the rental portion of World Wide Group and Rose Associates’ 252 East 57th Street — its first multifamily acquisition in New York City outside of Hudson Yards.

Turner said that move into residential is indicative of Oxford’s intention to diversify.

“Our acquisition of a [residential] tower here tells you that the evolution of the company in New York — or in London, where we’re in the same position — is not going to be [as] just an office company,” he said. “We’ll build out other sectors. That will be something that’s noticeable.”

And he noted that Oxford’s capital base from OMERS will double by 2030 as the plan’s membership grows, which means Oxford will have plenty of cash to invest.

“OMERS’ liabilities will grow, which means OMERS’ assets have to grow,” Turner said. “There’s a lot of dry powder.”

That growth could mean more ambitious developments in New York.

PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Carlock noted that Canadian companies are used to partnering with the government and are not likely to shy away from projects that require rezonings or public-private partnerships.

“I think the Canadian funds will be players for other municipal game changer-type things, not unlike the St. John’s terminal deal,” he said. “It is a very comfortable arena for the Canadians.”

Malcolm Hamilton, an expert on Canadian pension plans and a fellow at the Toronto-based think tank C.D. Howe Institute, said that if investments by Oxford and others in OMERS’ portfolio don’t pan out, the plan won’t be able to get on solid ground by 2025.

“Many of the Canadian pension funds now don’t have any gap at all, so in a sense they’re lagging their peers in not being fully funded,” he said, explaining that competing plans have started winding down the contributions members make.

“OMERS,” he added, “has not yet got to the point where they can start winding it down.”