Years before anyone called 57th Street “Billionaire’s Row,” developer Gary Barnett was gunning for a sales record at his Christian de Portzamparc-designed One57 in Midtown. In December, he got his wish, when his top penthouse sold for $100.5 million, setting a record for the most expensive apartment ever sold in Manhattan.

Today, that penthouse — which Barnett originally listed for $98.5 million and then hiked to $110 million — looks like it may hold the record spot for only a short while.

While developers have been attempting to hit new and higher markers for as long as they’ve been building, the latest crop of penthouses is moving New York City luxury real estate into another stratosphere.

“It’s not that prices rose to this level, but that a new housing category has been created,” said Jonathan Miller, president of real estate appraisal firm Miller Samuel.

The Zeckendorf brothers are asking $130 million at 520 Park Avenue, while the Chetrit Group is planning a $150 million unit at 550 Madison Avenue and Vornado Realty Trust could go as high as $175 million at its planned 220 Central Park South. In all, there are nearly a dozen existing or forthcoming units that will ask $100 million or more.

But even with construction budgets north of $1 billion, developers are poised to reel in huge profits.

“The numbers that are being discussed today are on top of any projected profits that were initially priced into the pro formas,” said attorney Ed Mermelstein, who has represented foreign buyers in buildings including One57. “When the projects were purchased, there was nothing in the market even close to selling at $100 million, so the numbers that are now being thrown around are just gravy.”

But the astronomical price tags do beg the question: At what point are developers breaking even with these projects? Also, how much wiggle room is there for discounts if the market starts falling?

“Developers today are facing extremely high land costs and so they are, a lot of the time, trying to put [high] prices on penthouses to make up the value they need to achieve,” said Robert Vecsler, executive vice president of Silverstein Properties, which is asking $60 million for a combined duplex penthouse at its under-construction 30 Park Place.

Sources said ultra-luxury projects cost about 10 percent more to build than your standard, multi-million-dollar condominium. Developers typically recoup their expenses and start to see a profit by selling condos at prices between $2,000 and $3,000 per square foot, which reflects the high cost of land and construction, as well as the price of top-shelf finishes, from imported marble to exotic wood to silk wall coverings.

Hard costs like land and construction alone, which averaged $750 per square foot a year ago, now average $1,000 per square foot.

And super-tall buildings — such as Macklowe Properties’ 432 Park, which has a $95 million penthouse — come with additional engineering expenses like sound attenuation, high-speed elevators and wind turbines.

Yet the pricing in the ultra luxury market seems to have little relation to costs.

“The amount of work you’re doing for new construction will be a lot, regardless of [whether you price units] at $10,000 or $2,000 a foot. That’s why developers are all going for the big whale,” said Roy Kim, Extell’s former top design executive, who is now head of development at Compass. “When Gary [Barnett] was building One57, if he followed the comp data sets for that area, there’s no way he’d come up with $10,000 per square foot for the project.”

And One57’s pricing has had a profound ripple effect.

“Trophy properties used to have to be an assemblage of a couple of apartments, created by the purchaser,” said Shaun Osher, founder and CEO of the brokerage Core. “Now, you have developers who are creating trophy properties.”

“Trophy properties used to have to be an assemblage of a couple of apartments, created by the purchaser,” said Shaun Osher, founder and CEO of the brokerage Core. “Now, you have developers who are creating trophy properties.”

Osher said the quality of those developments is also getting better, which is driving up prices.

That’s the case at Jared Kushner’s Puck Penthouses in Soho, where six penthouses feature luxe finishes like poured Terrazzo floors and $100,000 handmade La Cornue stoves.

Agent Nikki Field of Sotheby’s International Realty said Kushner spared no expense, even shelling out an astounding $10 million on change orders, such as increasing the thickness of the floor to 3.25 inches from 2.25 inches. Kushner Companies paid $19 million for the Puck Building in 1986 and is looking to sell out the condos there for a total of $204 million, according to a summary of the plan on the Attorney General’s website.

“It’s not because they’re foolish,” Field said. “They are appealing to the ultra high-net-worth purchaser.”

She said Kushner recently turned down a $60 million offer for the top penthouse and is holding out for the $66 million asking price, which is north of $9,000 per square foot. She said the closest comparable sale downtown was Walker Tower’s penthouse, which sold last year for nearly $51 million, or upwards of $8,400 per square foot.

Read on for a closer look at how three towers with stratospherically priced penthouses pencil out.

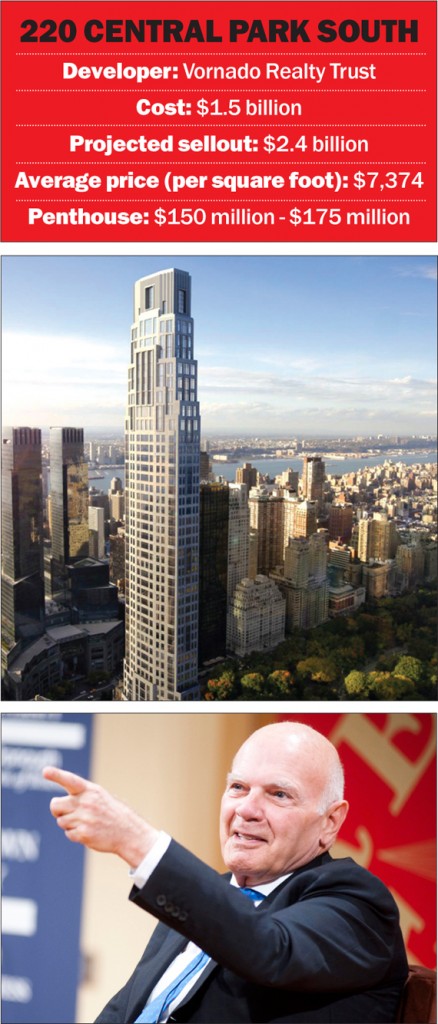

Fans of the Robert A.M. Stern-designed blockbuster 15 Central Park West see another legend-in-the-making at Vornado’s upcoming 220 Central Park South.

With 118 units, the limestone tower is projected to have a total sellout of $2.4 billion, including a penthouse that will ask between $150 million to $175 million, according to the recently approved condo offering plan filed with the AG.

“Similar to what we saw at 15 Central Park West a few years ago, where the prices there totally did not correlate to the market, 220 is that type of property,” Mermelstein said.

Vornado began assembling the site a decade ago, so it got in at a relatively low cost basis compared to what it would cost the firm to buy the land today.

In 2005, the REIT paid $132 million for a 20-story rental building, and then spent $40 million to buy out its rent-regulated tenants. In 2012, Vornado applied for permits to demolish the old building and build a new tower, but ran into a stubborn obstacle when Extell refused to vacate a lease for the parking garage under the site. But in 2013, after sparring for more than a year, Extell agreed to sell the land and air rights at 225 West 58th Street to Vornado for $194 million.

While enduring the multi-year delay, Vornado’s project became more and more expensive. What started out as a $400 million project, according to the REIT’s 2010 annual report, is now pegged at $1 billion.

As of September, the REIT had invested more than $560 million into 220 Central Park South, including $456 million for the land and development rights and another $106 million in soft costs, according to regulatory filings.

Shortly after completing the assemblage, Vornado secured $1.1 billion in debt, including a $600 million loan from Bank of China and a $500 million mezzanine loan to cover development costs.

But the wait has had a major upside.

Vornado executives bided their time by watching the market, and increased prices at 220 Central Park South accordingly. (“We hear that the 1,000-foot tall, direct park-view apartment tower under construction on 57th Street is pricing at $6,500 per square foot. Our 220 Central Park South site, just down the block, is better,” read Vornado’s 2011 annual report.)

Meanwhile, Vornado estimates that the project’s pièce de résistance, its Central Park-facing site, has tripled in value since the REIT acquired the property.

“The market has risen to the point where the delay was enormously to our benefit,” CFO Stephen Theriot said during a 2013 earnings conference call, in which he estimated the “raw site” is worth north of $1 billion. A more recent estimate, from 2015, pegs the value of the land for which Vornado paid $456 million at $1.2 billion.

“The market has risen to the point where the delay was enormously to our benefit,” CFO Stephen Theriot said during a 2013 earnings conference call, in which he estimated the “raw site” is worth north of $1 billion. A more recent estimate, from 2015, pegs the value of the land for which Vornado paid $456 million at $1.2 billion.

“Our basis in our site is $1,000 a foot,” Theriot said. “So we think we have a remarkable profit in just the land.”

With a projected sellout of $2.4 billion, the building’s prices will average $7,374 per square foot. (Six of the building’s 118 units were not in the offering plan and are not part of that calculation.)

In an August report, analyst Alexander Goldfarb of investment banking firm Sandler O’Neill estimated the cost of 220 Central Park South at $3,000 per buildable square foot, and projected sale prices of roughly $8,000 per square foot. Adjusting for the taxes a REIT must pay, he estimated an after-tax profit of $1.2 billion.

“Even though you’re talking about big numbers, by the time they net it all out, they won’t make that much,” he maintained. “There’s a huge amount that goes to taxes.”

At the same time, the market has become “quite frothy,” Goldfarb noted, which is why Vornado is willing to spend so much money on the development.

He added: “It will certainly be a showcase project.”

Having left their imprimatur on Manhattan’s West Side with 15 Central Park West, brothers Arthur and William Lie Zeckendorf are now looking for 520 Park Avenue to leave a similar mark across town.

Like Vornado, the Zeckendorfs spent years piecing together the 178,000-square-foot site, a hodgepodge of six parcels, including two that were owned by partners Eyal Ofer’s Global Holdings and Rafael and Ezra Nasser’s Park Sixty LLC. And like 220 Central Park South, the building is also designed by Stern.

In 2013, the developers finally completed the assemblage, when they bought air rights from Christ Church for more than $30 million.

In all, the land cost was “significantly less than market value” since the majority of it was acquired before prices shot up in 2013, said Dustin Stolly of commercial brokerage JLL, which arranged the Zeckendorfs’ $450 million construction loan from the U.K.-based Children’s Investment Fund in October. Stolly said the loan will cover close to 75 percent of the total cost. Based on that ratio, the project cost is roughly $600 million. But that doesn’t include the cost of land, which would add millions to the bottom line.

According to 520 Park’s offering plan, the 31-unit limestone tower will rise 51 stories, with 31 full-floor units starting at $27 million. The total sellout is expected to be $1.2 billion, with prices averaging $6,742 per square foot. If that’s achieved, the Zeckendorfs will be left with $600 million in gross profit.

The $130 million penthouse is a triplex that will measure 12,400 square feet and ask $10,483 per square foot.

Stolly said the building has a break-even price of $2,500 per square foot, meaning that the Zeckendorfs must charge buyers at least that in order to recoup their expenses. “They have a terrific land basis,” he said. “They’re going to make a tremendous amount of money.”

Like other luxury towers that are rising along Billionaire’s Row, 520 Park’s pricing is modeled after resales at 15 Central Park West, which on average go for $10,000 per square foot.

“I can’t tell you when the $13,000-a square-foot [record] set on the 19th floor of 15 Central Park West gets broken,” William Lie Zeckendorf Jr. told Bloomberg View in 2013. But, he added, “A lot of stuff underneath it is being dragged up by it. Everyone is using it as a benchmark.”

Apparently, even him.

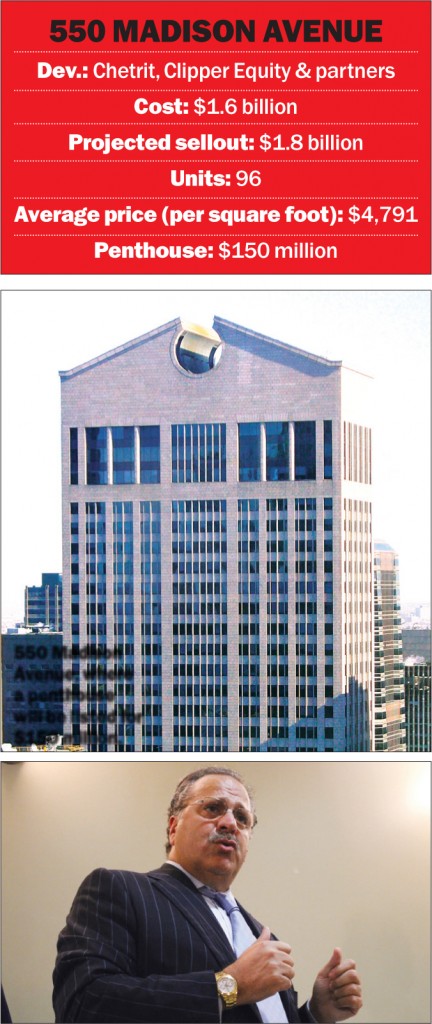

When electronic giant Sony put its headquarters at 550 Madison Avenue on the market in 2012, executives touted the building to potential buyers by playing up its tremendous “unlocked value.” With the luxury condo market on fire, new owner Joe Chetrit may have the key: Plans call for residences asking $4,791 per square foot on average, a premium over office prices in the area.

The Chetrit-led investor group, including Clipper Equity’s David Bistricer, beat out 20 other bidders in 2013, paying $1.1 billion for the building. The developers put down a $100 million deposit. They subsequently landed $925 million in financing for the deal from SL Green Realty, plus a $600 million mortgage from Bank of China.

At the time of the sale, Sony negotiated a three-year lease for an undisclosed sum. But the rent will cover Chetrit’s real estate taxes, the building’s operating expenses and mortgage debt service, according to Robert Ivanhoe, chair of the global real estate practice at the law firm Greenberg Traurig, which represented Sony in the deal.

At the time of the sale, Sony negotiated a three-year lease for an undisclosed sum. But the rent will cover Chetrit’s real estate taxes, the building’s operating expenses and mortgage debt service, according to Robert Ivanhoe, chair of the global real estate practice at the law firm Greenberg Traurig, which represented Sony in the deal.

Plans call for the building to be converted into luxury condos, a hotel and high-end retail. The residential portion will include 96 apartments, for a total projected sellout of $1.8 billion. The sprawling 21,504 square-foot triplex penthouse will ask $150 million, as TRD exclusively reported. While that price tag has astounded many in the industry, at $6,975 per square foot, it’s actually less on a per-square-foot basis then the penthouse at 520 Park Avenue.

Sources said the project’s break-even price for selling units is close to $3,000 per square foot, making its profit margins “somewhat tighter” than comparable, ground-up developments. Another risk is Sony’s three-year lease, which ends next year. By the time Chetrit empties and renovates the building, source noted, the luxury residential market could turn.

But brokers still say they believe the project will be a runaway success.

The building’s commercial space — some 300,000 square feet — gives the developer an extra financial buffer, should the residential market turn. Taking a page from One57, Chetrit is likely to convert the bottom floors into a hotel. At One57, Extell sold the 210-room Park Hyatt hotel to Hyatt Hotels Corporation for $390 million.

At 550 Madison, sources said the retail and hotel components could be worth a combined $400 million to $600 million.

There is precedent for that price range, too. Last year, Vornado and Crown Acquisitions paid $700 million for the retail condo at the St. Regis Hotel. And Harry Macklowe is in contract to buy the nearly 75,000-square-foot retail space at 432 Park Avenue for $450 million.

“The retail is extremely valuable,” said Faith Hope Consolo, chairman of Douglas Elliman’s retail leasing and sales division. She said monthly rents on Madison Avenue above 57th Street top $1,800 per square foot, while rents below 57th Street, where the Sony building is located, are roughly $1,000 per square foot. In two years, she said the ground-floor retail at 550 Madison “could easily be $1,500 per square foot.”

“This is a trophy property in one of the best locations in the city,” she said.