For a roughly eight-week stretch, New York real estate players were facing a doomsday scenario in the form of a looming pied-à-terre tax that had garnered broad support in Albany.

But over the course of 12 hours on March 25, lawmakers abruptly pivoted away from an annual pied-à-terre assessment in favor of restructuring the city’s transfer tax system. By the evening of the 25th, the pied-à-terre tax wasn’t quite dead, but it was “headed there,” according to published reports.

How did one of the most popular political proposals this legislative session get scrapped at the 11th hour?

For weeks, the industry lobbied furiously against it, arguing that it would lead to a real estate Armageddon — one developers and brokers warned would tank the market and alienate wealthy buyers who are crucial to the city’s economy.

REBNY President John Banks called the tax a “knee-jerk” response to public housing and mass transit problems that was being rammed into the budget before a comprehensive study was even conducted on the long-term impact.

“The public is growing tired of government just throwing money at problems without doing the research and analysis to propose real solutions,” Banks said.

But it was partly the logistics around taxing pieds-à-terre, rather than the furious lobbying, that did in the proposal.

As lawmakers huddled in Albany hammering out details of the budget, which was due to be adopted at press time, the city’s arcane property tax system posed hurdles. A version of the bill that would have taxed LLC purchases was deemed impractical, given that some of those properties are, in fact, owned by primary residents.

Figuring out how to tax pieds-à-terre in co-ops was also proving to be a headache, as were concerns about the city’s ability to administer the tax, considering its already convoluted system for assessing residential real estate. Enforcement was another question mark, with some predicting that certain second-home buyers would try to game the system.

Unwilling to give up on much-needed new revenue for the crumbling transit system — which has a $40 billion budget gap — lawmakers quickly formed a consensus around transfer taxes. While light on details, at least one proposal called for a transfer tax on sales of $3 million-plus properties, with a higher tax rate for sales above $5 million.

“It’s an easier program to administer,” Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie told reporters in Albany, citing “technical difficulties” with a pied-à-terre tax.

“If there’s a better way to do it, fine,” Gov. Andrew Cuomo said on WNYC with Brian Lehrer once the transfer tax proposal was floated. “We need the tax. I think it’s justifiable.”

While they were not thrilled about luxury real estate getting hit with another tax, there was a collective feeling among developers and brokers that the industry had dodged a bullet. And real estate sources conceded that a one-time tax is far preferable to an annual assessment.

“I understand — and I think so many people do — the MTA issue. It’s awful, and it needs to be better,” said Steven James, CEO of Douglas Elliman’s New York brokerage.

James opposed the pied-à-terre tax but predicted buyers would tolerate a slightly higher transfer tax, much like they got used to the mansion tax.

“It became another fee; I think this could be the same way,” he said.

But if real estate interests got a reprieve this time, the industry is still very much in the crosshairs of progressive lawmakers.

“The real estate industry shouldn’t mistake any hesitation by the legislature or governor as lack of political consensus on a pied-à-terre tax,” said Evan Thies, co-founder of Pythia Public Affairs, a communications and political strategy firm.

“It’s really only likely that law and logistics would stop this train from rolling,” he said. “It is more likely politicians will somehow prevail and lead to the passage of the pied-à-terre tax before the end of the session in June.”

A transit system in crisis

The case for an MTA cash injection should be obvious to anyone who’s ridden the subway lately.

Proponents of the pied-à-terre tax argued it could generate up to $650 million by imposing a levy on second homes valued at $5 million or more. (The proposal calls for a sliding scale starting at 0.5 percent for properties valued at $5 million to $6 million and jumps to 4 percent on properties of $25 million or more).

Cuomo threw his support behind the proposal in March after a bill to legalize (and tax) marijuana was dropped from the state budget; he said the state could leverage the revenue from the pied-à-terre tax to raise $9 billion in bonds for the MTA.

Critics weren’t convinced the tax would be so fruitful, however.

In late March, an industry-backed analysis found it would only generate $372 million a year. “It’s not going to bring in as much money as they hoped,” said Martha Stark, a former city Department of Finance commissioner, who conducted the analysis with Greg Heym, chief economist of Terra Holdings.

Regardless of what the tax could rake in for state coffers, proponents of the measure (and others like it) have been emboldened since November’s elections, when Democrats seized control of the state Senate for the first time in years, giving them control of both legislative chambers and the governor’s office.

During a March 27 interview on public radio, Sen. Brad Hoylman, who introduced the proposal in 2014, rejected the notion that a pied-à-terre tax was too complicated.

“Those are obviously concerns that could have been worked out if there was the political will,” he said.

He blamed special interest groups for descending on Albany in their SUVs to lobby against the measure. “I’m hopeful that we can resuscitate it,” he said, “given the revenue that’s needed on a consistent basis for the MTA.”

The transfer tax proposal could generate $300 million to $400 million in state revenue, according to estimates by city Comptroller Scott Stringer’s office, which proposed restructuring the city’s transfer taxes in November. It’s unclear if that proposal is currently the one being considered in Albany, but it called for eliminating the mortgage-recording tax and applying a sliding transfer tax to all properties that would increase with the sale price.

Assembly member Linda Rosenthal characterized the pied-à-terre tax as a no-brainer.

“We desperately need money for the MTA, and people who can afford a pied-à-terre that costs millions and millions of dollars certainly can afford to pay a tax on it,” said Rosenthal, a co-sponsor of the bill.

“Oligarchs and wealthy people from other countries are parking their money in New York City,” she said. “We’re not harming anyone except those wealthy purchasers. My question is, why are we protecting them?”

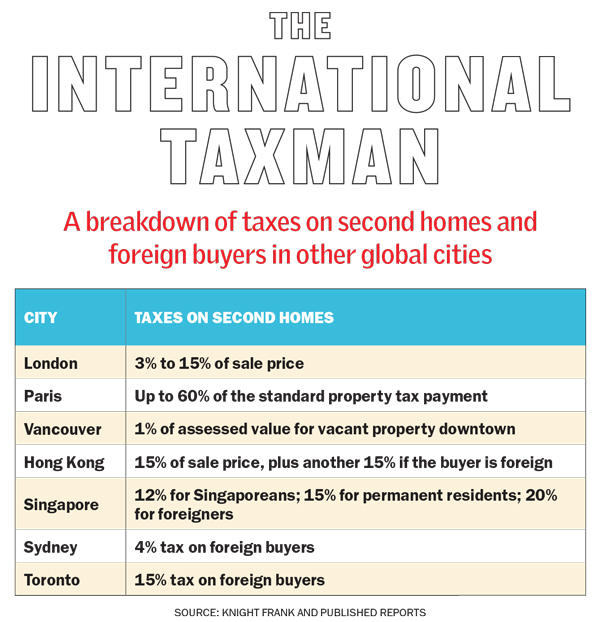

Despite the debate surrounding the idea, New York is one of the last international gateway cities to consider a tax on second homes.

In Hong Kong, second-home buyers (including those from China) pay 15 percent of the home’s value, while foreigners owe an additional 15 percent. Meanwhile, in London, vacation homes are taxed between 3 and 15 percent of a property’s value, depending on the cost, while in Vancouver, owners are taxed 1 percent of the assessed value on empty residential properties located downtown.

Developer William Zeckendorf — whose 15 Central Park West and 520 Park Avenue are among the city’s priciest condo buildings — endorsed a transfer tax over a pied-à-terre tax, saying it would raise more money “without negative consequences.”

In an op-ed in Crain’s late last month, Zeckendorf argued that the “growth dynamic” that made New York so vibrant had recently met “ideologically driven resistance” that threatened to hurt the city’s economy.

“Ideological walls can be damaging,” he argued, and “unless cooler heads prevail, New York will soon find out just how much.”

‘Self-inflicted chaos’

As Zeckendorf suggested, the proposed pied-à-terre tax was the scourge of dinner parties and industry events in the weeks leading up to April 1.

“The minute the news of the Ken Griffin sale came out, I was like, ‘Oh shit,’” said the head of one residential brokerage firm.

Developer Sharif El-Gamal, whose Soho Properties is developing luxury condos at 45 Park Place in Lower Manhattan, had a similar assessment: “This would be the most lethal form of self-inflicted market chaos that would have a ripple effect across the whole economic engine of New York City.”

David Schwartz, a principal at Slate Property Group, said paying to fix the subway system is “good for business.”

But he said if property values dropped as a result of a pied-à-terre tax, the city’s total property tax revenue could also take a hit.

According to Stringer’s office, there are 5,400 pieds-à-terre in New York City valued above $5 million that would presumably be impacted out of the gate.

Appraiser Jonathan Miller said if a pied-à-terre tax was instated he’d expect it to most severely impact the very top of the luxury market. Properties valued at $25 million or more could lose 30 percent of their value “overnight,” he argued.

Others cited the far-reaching tentacles of the real estate business — from architects to construction workers to designers to building managers and staff — in their quest to render the tax permanently dead.

“There’s a whole infrastructure around real estate,” said Elizabeth Ann Stribling-Kivlan, president of Stribling & Associates, adding that several of her firm’s buyers planned to walk if the pied-à-terre tax was passed.

Lou Coletti, president of the Building Trades Employers’ Association, said there’s no question the tax would stunt construction in the city.

“We don’t want any additional public policies or taxes that will impede the continued growth of New York City,” he said. “I don’t understand why it’s an option even being debated.”

‘Broken system’

In a stroke of irony, it was the city’s existing property tax system that helped deliver the industry a win — at least a temporary and partial one.

Current tax law requires co-ops and condos to be assessed as if they were rental properties, a scenario that’s resulted in the “severe and persistent undervaluation” of some of the priciest apartments, the Furman Center said in a 2018 policy brief. Last year, the city’s Independent Budget Office — a nonpartisan organization that provides information about the city’s budget and tax revenue — estimated co-ops and condos were undervalued by 20 percent compared to their true market value.

“Fundamentally, the property tax system itself upon which this is going to be layered is absolutely screwy,” said former DOF Commissioner Stark, who is now policy director at Tax Equity Now New York, which filed a 2017 lawsuit challenging the current tax system.

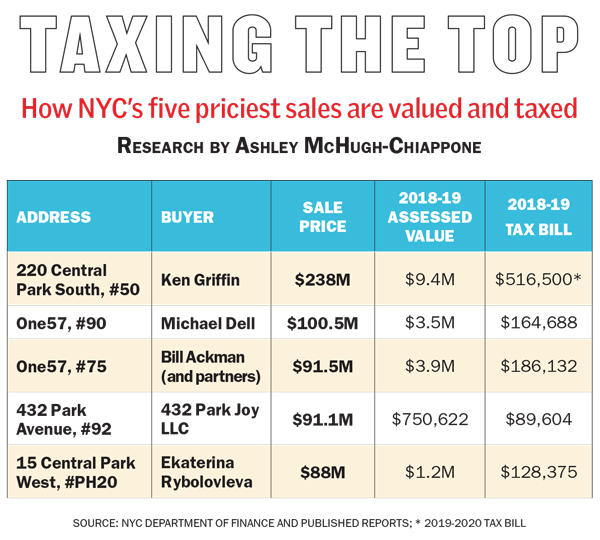

Take the Griffin apartment: Even after it sold for a record-breaking $238 million, it was assessed at just $9.4 million, with annual taxes of around $516,000.

And it’s hardly an outlier. Michael Dell’s penthouse at One57 — which he purchased for $100.5 million in 2014 — had an assessed value of only $3.5 million, according city tax records. Based on that value, his taxes would clock in at $164,688 this year. Another penthouse at One57 — purchased by Bill Ackman for $91.5 million in 2015 — had a assessed value of only $3.9 million, making his 2018-2019 tax bill $186,132.

“There’s tons of revenue being left on the table with high-value properties paying minuscule amounts of property taxes,” said Jordan Barowitz, who oversees government and media relations for the Durst Organization.

Although Durst, which develops high-end rentals, has little at stake in the pied-à-terre tax debate, the developer supports the 2017 lawsuit that seeks to overhaul the city’s property tax system. “The property tax system is too dysfunctional to layer on additional taxes,” Barowitz said.

Despite that widespread view, overhauling the existing system would be a laborious and expensive project. One city official estimated it could cost billions of dollars to do it in a revenue-neutral way.

“Is [the current property tax system] an irrational approach that causes bizarre distortion? Yes,” the official said. “Is there a good way to get to a more rational system without sticking it to a lot of people? No.”

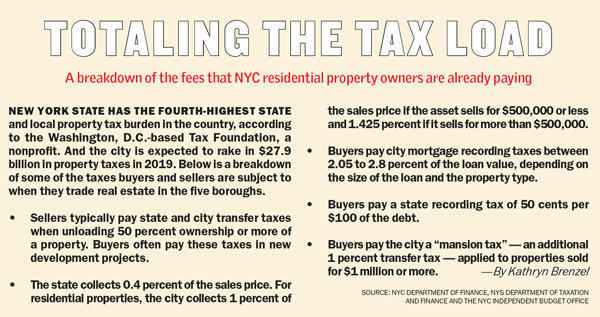

New York state also has the fourth-highest state and local property tax burden per capita at $2,697, according to the latest figures from the Washington, D.C.-based Tax Foundation, an independent nonprofit. In fiscal year 2018, the city raked in $27.7 billion in property taxes, according to an annual report released by the de Blasio administration.

Already, brokers in Florida and other low-tax states say they’ve seen an influx of buyers from New York, New Jersey and Connecticut as a result of the new $10,000 cap on state and local tax deductions signed into law by President Donald Trump.

Starwood Capital’s Barry Sternlicht is one of them. After he sold his Greenwich, Connecticut, home in 2016, the hedge fund officially relocated last year to Miami, also from Greenwich.

Echoes of Amazon

While the pied-à-terre tax may be off the table for this budget, lawmakers are likely to take up the issue again soon.

In mid-March, Richard Gottfried, another co-sponsor of the bill in the Assembly, said the state shouldn’t be choosing between a pied-à-terre tax and congestion pricing, the proposed tax to drive into the center of Manhattan — another avenue of revenue the state has been pursuing.

“The financial needs of the MTA are so enormous that it’s not a question of congestion pricing versus pied-à-terre tax; we need them both,” he said. “But the fact that the pied-à-terre tax is entirely focused on people with enormous wealth makes it especially justifiable.”

While the real estate industry disagrees, its influence has taken a hit since the November elections. And a growing number of local politicians — including City Council Speaker (and mayoral hopeful) Corey Johnson and state Sen. Michael Gianaris — have refused to accept campaign donations from developers.

John Kaehny, executive director of Reinvent Albany, a government watchdog, said that even without passing a pied-à-terre tax, tenant advocates scored a tactical win during this latest round of budget negotiations by shifting the real estate industry’s focus from the impending rent-stabilization debate.

“Tenant groups are making them play defense now and are making them expend lobbying resources and call in favors from elected officials,” Kaehny said.

Basil Smikle, former executive director of the New York Democratic Party, said the pied-à-terre tax is “one component of a larger progressive platform” that Democrats have adopted in New York and nationally.

“There is this growing movement of people on the left and right that believe wealth inequality is so great that something has to be done,” he said.

Smikle believes that movement will fuel another pied-à-terre tax push in New York. “The mayor is on his way out, so to speak. Anyone coming after him, I don’t see how they don’t pick up the baton and run with it,” he said.

A second-home tax also has a crucial selling point for elected officials: It doesn’t impact constituents with voting power, said Mitchell Moss, professor of urban policy and planning and director of the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy & Management at New York University.

“I actually believe that legalization of cannabis and taxing it would be a wiser path,” he said. “The tax on pieds-à-terre is based on the widely practiced policy of taxation without representation. You tax people who are not eligible to vote in the jurisdiction, imposing the tax, and that’s one reason why this tax has the support of the legislators.”

In recent weeks, Banks has denounced a slew of proposed policy changes in addition to the pied-à-terre tax — including those involving rent regulation and prevailing wages for construction workers — that he argued would “throw a huge wet blanket” on the industry.

In addition, the pied-à-terre tax fight comes on the heels of Amazon backing out of its plans for a campus in Long Island City.

The collapse of that deal stemmed from political opposition from elected officials who claimed the e-commerce giant was getting sweetheart tax breaks. And many of those players are the same officials who now want to up taxes on luxury properties.

Nathan Berman, the managing principal of Metro Loft Management, said that if Amazon was “an historic opportunity irresponsibly wasted,” imposing a pied-à-terre tax on the “very group that feeds much of the growth and prosperity of this city would be suicidal.”

— Additional reporting by Kathryn Brenzel and Erin Hudson