Before Harry Helmsley began syndicating buildings in the late 1940s, real estate investors had few choices beyond deciding which properties to buy.

Things are clearly different today.

By offering shares of skyscrapers like the Empire State Building to small-time buyers, the legendary developer set off a wave of innovation that transformed real estate investment. Those decades of innovation mean that today, investors looking to spend on buildings have more choice than ever — from buying assets directly, to investing through a bevy of vehicles such as real estate investment trusts, wealth managers, private funds and so-called funds of funds, which invest in private funds or REITs. And the rapid growth of real estate crowdfunding in the past few years has added yet another, though still largely untested, option.

Tracking returns for the entire landscape of investment vehicles is easier said than done. Wealth managers, for example, are notoriously opaque, while crowdfunding is too new to offer reliable data.

But the two most popular investment vehicles among investors without the resources or inclination to buy their own buildings or partner in new developments — namely, private real estate funds and REITs — are tracked by a bevy of analysts and researchers.

This month, The Real Deal combed through data and research papers to compare how returns from those two vehicles stack up against each other.

While initially it might seem that REITs are far better moneymakers, a closer look suggests a mixed picture.

Who’s on top?

“Only death, taxes, and REITs are inevitable,” claimed a recent issue of the NYU Schack Institute’s Premises Magazine. The same could be said of private equity real estate.

Investment in both public REITs and private real estate funds boomed in recent years. In 2014, U.S. public REITs raised $63.6 billion in capital, while the total share value of all publicly traded REITs grew to $900 billion as of March 31, according to the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts, which represents the REIT industry.

During the same period, private real estate funds raised even more: $97.7 billion, the highest figure since 2008, according to research firm Preqin.

Some data indicates REITs have drummed up far higher returns than their private real estate fund counterparts.

A recent study by several economists in the Netherlands analyzed pension fund investment in global real estate between 1990 and 2011. It found that pension funds that invested with REITs scooped up gross profits of 10.9 percent, while those that went through private funds or asset managers got only 7.23 percent a year, on average.

Since many private funds charge higher management fees than REITs, the real difference is even higher.

There is no indication this has changed since 2011.

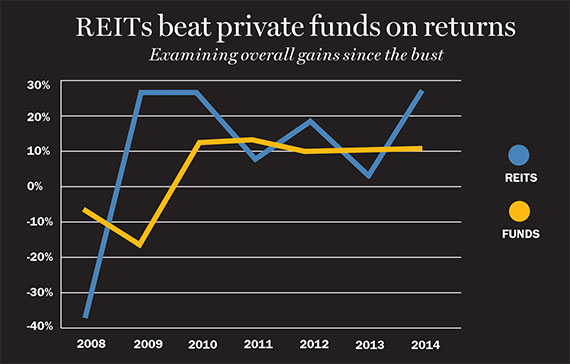

In 2014, U.S. equity REITs generated gross returns of about 28 percent, according NAREIT (see chart).

Meanwhile, recorded returns from institutional investment in private real estate were nearly 12 percent, according to the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries’ Property Index, which some in the industry use as a rough indicator of private-fund performance.

But one source, Joseph Pagliari, a professor of real estate at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, said those numbers aren’t as cut and dried as they may appear. He said REITs tend to be more leveraged than private institutional real estate. After factoring in that additional risk, he saw the difference in average returns evaporate. “In the long run, the performance of REITs and private institutional real estate funds is nearly identical,” he said.

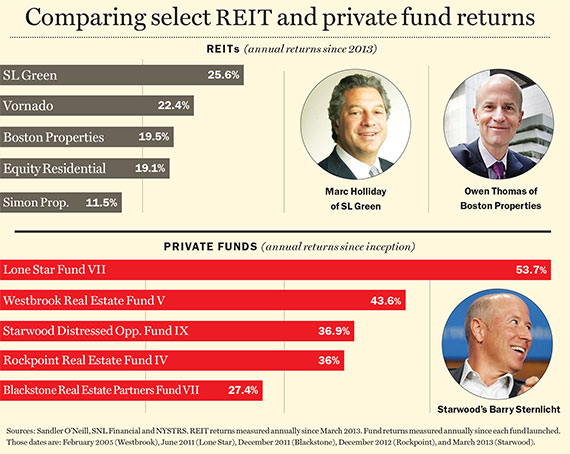

Moreover, some top private real estate funds have performed far better than leading REITs, as our chart shows.

Stephen Schwarzman’s behemoth private equity firm the Blackstone Group is a case in point. Blackstone’s flagship fund, Real Estate Partners Fund VII, has thrown off massive annual returns of 27.4 percent since it launched in 2011, according to data from the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System, which has invested in the fund.

Meanwhile, Barry Sternlicht’s Starwood Capital’s Distressed Opportunity Fund IX has generated even higher annualized returns, 36.9 percent, since March 2013.

Both of those numbers trounce leading REITs and help explain why both fund managers have been so successful at raising capital.

“Private real estate funds have generally done very, very well,” said Stephen Ellis, director of financial services equity research at investment research firm Morningstar.

With no clear evidence that REITs perform better than private funds, an investor’s choice often boils down to individual preferences.

Stock shock

There are, of course, some key differences between the two that investors need to consider before throwing down cash.

While both REITs and private real estate funds allow investors to buy a share of a real estate portfolio, the way they pay out returns is different.

Many of those differences stem from the fact that most major REITs — like SL Green Realty, Vornado Realty Trust and Boston Properties — are publicly traded and legally required to pay out 90 percent of their income to investors in return for tax relief. Their investors make money through dividends and stock appreciation.

Private funds, on the other hand, are not listed on stock markets, although their managers (like the Blackstone Group), sometimes are. Most private equity funds require a significant minimum investment and many have a fixed life span, meaning investors will only get paid out in full after a number of years.

“Public real estate benefits from liquidity. People know it’s easier to get in and out,” said Alex Goldfarb, managing director of equity research at investment banking firm Sandler O’Neill and Partners.

But publicly traded REITs are also subject to fluctuations in the stock market. In the long run, sources say, that doesn’t matter much, because REIT performance is ultimately tied to real estate values. But in the short term, it can add volatility and give investors the jitters.

Another point of distinction is transparency. As public companies, REITs face greater scrutiny than some private funds.

“There is a whole industry around publicly listed REITs, with analysts and press following them,” said Piet Eichholtz, an economist at Maastricht University in the Netherlands and one of the authors of the above-mentioned report.

And while stock price fluctuations may add volatility, they also give a more immediate sense of asset values, explained NAREIT’s senior vice president of research Brad Case. “What’s happened in stock markets is that the true value of assets is revealed,” he said.