Early last month, Gov. Andrew Cuomo climbed into Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1932 Packard convertible and made the inaugural trip across the new Tappan Zee Bridge. The celebratory drive ended with a staged press event where he touted the nearly $4 billion project, now officially renamed the Governor Mario M. Cuomo Bridge in honor of his father.

But the celebration was premature.

The next day, when the soaring silver structure was scheduled to open to traffic, the New York State Thruway Authority announced a “potentially dangerous” situation: A portion of the adjacent old bridge was at risk of collapsing and hitting the new one.

Forty-eight hours later, the second span opened after getting the all-clear from engineers. The next day, however, the New York Times reported that Cuomo’s administration had rushed the contractor to meet a late-August deadline, despite potential extra costs. And, all the while, the governor’s Democratic primary challenger, Cynthia Nixon, was accusing him of putting drivers in danger for a self-serving public spectacle. (The Cuomo administration has denied this.)

The bridge scandal, however, didn’t prevent Cuomo from easily defeating Nixon in the following week’s primary election.

“It’ll be a relatively minor kerfuffle,” said David Birdsell, dean of Baruch College’s Marxe School of Public and International Affairs, noting that “if the old Tappan Zee fell into the new span, that’d be a different story.”

Related: Albany’s power structure resets

“But it will lend force to a long-standing critique of the governor that he is controlling — that he pursues his agendas to the point of recklessness,” Birdsell added.

In his two terms as governor, Cuomo’s positioned himself as a modern-day Robert Moses — someone who will steer large, complicated projects to completion and move New York’s aging infrastructure into the 21st century.

And Cuomo, like Moses, has something of a track record of making announcements only to add conditions to them later or leave out details about how the money will be spent.

“I’ve been puzzled by it for years,” said Victor Bach, senior policy analyst for the nonprofit Community Service Society, “because [some of] these are grand announcements that are usually made in the State of the State and it’s very hard to follow that money as it’s allocated.”

Related: What would Tish James do?

As Cuomo moves toward next month’s general election — where he will face his Republican challenger, Dutchess County Executive Marc Molinaro, along with Nixon, who may still run on the Working Families Party line, and several other third-party candidates — the clock is ticking on his next economic development push.

For now, Cuomo is preparing for a nearly guaranteed third term — a win for New York City’s $1 trillion-plus real estate industry, which has pumped millions of dollars into his campaign war chest over the years.

In addition to big infrastructure projects, real estate is closely watching (and lobbying him on) the rest of his agenda, which includes everything from affordable housing to suburban development projects — all high-stakes areas that amount to billions of dollars in tax breaks and potential profits. And with the Republican Party in jeopardy of losing control of the state Senate, Cuomo could become even more crucial to protecting the interests of the Real Estate Board of New York, the industry’s powerful lobbying group.

“REBNY is in for a rude awakening,” former New York City Comptroller John Liu, who won the primary for a state Senate seat, told The Real Deal in an email last month (see related story on page 38).

And whether the industry continues to get returns on its investment in Cuomo remains to be seen.

Cuomo’s cozy relationship with the industry could be subject to change if he is planning to run for president in 2020, which he is widely expected to do — and with the more liberal wing of the Democratic Party making gains in Albany. While Nixon wasn’t able to pull off an upset in the primary, she moved Cuomo to the left on a slew of real estate and other issues.

“He’s got higher political aspirations, and I think everyone knows that,” said one New York City-based developer, who asked not to be named. “Naturally, he needs to focus on things that will translate into votes. It’s hard to blame someone for looking at things like that.”

Promo projects

Cuomo has spent a lot of time attacking President Donald Trump and boasting about stepping in to right the president’s wrongs.

Last month, for example, he criticized the president for failing to push through a $1.5 trillion federal infrastructure program, while touting New York as having “the most aggressive building program in the United States of America.”

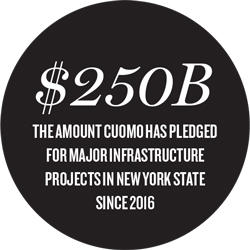

In June, the governor announced his $150 billion infrastructure plan, which will kick off in 2020. That program builds on the $100 billion initiative he announced two years ago, which includes a makeover of LaGuardia Airport, the expansion of the Javits Center and the creation of Penn Station’s Moynihan Train Hall in the James A. Farley Post Office. While state Budget Director Robert Mujica said the administration doesn’t announce specific projects until the financing is secured, the infrastructure plan will depend on future federal, local and private funding. That plan includes $66 billion for a handful of transit-related projects, including the Port Authority Bus Terminal and the South Brooklyn Marine and Red Hook terminals.

In many cases private developers and construction firms will be tapped to do the work, while commercial and residential landlords with buildings in close proximity will benefit from the badly needed upgrades.

So getting their financial buy-in was pretty much a given. Cuomo administration officials told TRD that 23 percent of the funding for both infrastructure plans is coming from the private sector.

The Moynihan Station project is expected to wrap in 2020.

A source familiar with the Moynihan project said Cuomo is attracted to striking public-private partnerships because it allows him to shift the risk of time and cost overruns.

“I think [Cuomo] has realized that whatever you do, government is going to suck at delivering projects on time and on budget,” the source said.

Some have also pointed out that the governor has mostly chosen to pin his name to large, visible projects, like work at LaGuardia and JFK, that have an impact beyond New York and will get more political play.

Philip Plotch, director of St. Peter’s University’s public administration program and author of the book “Politics Across the Hudson,” said Cuomo has shied away from projects that would be impossible for him to complete, including the MTA’s long-delayed East Side Access, which would connect the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central Terminal.

“From his perspective, there’s not a lot of upside to taking over a problem that he can’t solve,” Plotch said. “He doesn’t set himself up for failure.”

Tyrone Stevens, a spokesperson for the governor, called that critique “bogus.”

“After years in which our infrastructure was allowed to crumble and decay, Gov. Cuomo has invested in achievable projects that strengthen communities and the corridors that connect this state,” he said. “This administration will continue to focus on delivering real and lasting improvements, not empty promises and overhyped rhetoric.”

The Penn promise

One exception to his surefire approach may be the governor’s plans for Penn Station, where the funding is still very much in flux.

In January 2016, Cuomo announced a grand vision for redeveloping the aging station, dubbed the Empire Station Complex, a name that has since been dropped from public announcements.

And last year Cuomo followed that up by creating a task force of politicians and real estate execs to come up with a sweeping plan to present to the federal government. Ironically, that infrastructure council included one of Trump’s closest friends and donors, Vornado Realty Trust’s Steve Roth.

So far, Cuomo’s more realistic proposals have been mostly cosmetic.

In September, he announced plans for a new entrance to Penn at 33rd Street and Seventh Avenue and said a full overhaul of the station should wait until the $30 billion Gateway Tunnel project — which includes creating an entirely new train tunnel between New York and New Jersey — gets going. But in doing that, he has tied Penn’s fate to another project that has faced major delays.

Though some of the Gateway funding has been allocated, the bulk of it has been held hostage by the Trump administration. Much of the real estate industry supports a solution.

“Moving people to and from New Jersey is part of the lifeblood of NYC,” said REBNY President John Banks. “If one or both of the cross-Hudson tunnels were to become unavailable, it would be calamitous for our economy.”

Several major developers — most notably Vornado, Related Companies and Brookfield Property Partners — have a lot riding on the area and on those upgrades.

Vornado, Related and Skanska are developing Moynihan Train Hall, which sits across the street from Penn Station and will include 730,000 square feet of office, 120,000 square feet of retail and a 255,000-square-foot train hall for both Amtrak and the LIRR.

Vornado also owns more than 9 million square feet of property around Penn Station. Related is, of course, building its 26-acre Hudson Yards development, and Brookfield has its giant Manhattan West project — both blocks from Penn.

Vornado and Related will also profit from Moynihan’s retail leases — as well as about $400 million in tax breaks earmarked for construction of the train hall.

And Vornado has additional business in front of the state.

It’s negotiating with the Cuomo administration over the retail it owns under 33rd Street. In order to create the new Penn Station entrance, the state will need to buy out the REIT’s long-term lease. While the state has not disclosed how much the new entrance will cost, Mujica said the money will come from the MTA’s $33.2 billion capital plan and that the state will foot the rest of the bill.

Additionally, a full redevelopment of Penn Station would put about 2 million square feet of Madison Square Garden’s highly coveted air rights in play.

Vornado is currently best positioned to take advantage of those rights — which can only be tapped if they coincide with a significant transit improvement project.

But others are clearly hungry for the development work.

Vornado, Related and Skanska weren’t alone in vying for the Moynihan project — a telling sign of just how much skin the real estate industry has in the game.

A team comprised of Brookfield and Turner Construction and another including Silverstein Properties, Star America Infrastructure Partners and Taubman were also in the running, according to RFPs obtained by TRD through a Freedom of Information Law request. Representatives for those teams declined to comment.

Developers undoubtedly believe there is a lot to gain from an upgraded Penn.

“Transportation where the quality isn’t there erodes confidence in the city — and all developers are driven by that marketplace,” said Time Equities founder Francis Greenburger, who sold out an office condo conversion two blocks from Penn Station on 33rd Street back in 2013 and unloaded the building’s two retail condos in 2016.

Greenburger noted, however, that even in its current state, “Penn was a plus” for that project.

Cuomo has something of a track record of making announcements only to add conditions to them later.

Chris Ward, a former executive in AECOM’s New York office, put it more bluntly: “Penn Station is a hellhole, matched only, probably, by the Port Authority Bus Terminal,” he said. “So we’ve got to start now. Is [the plan] perfect? No. But it’s the politics of engineering necessity.”

Ward characterized Cuomo’s approach of forging ahead with the project — even without all of the funding lined up — as strategic. “I think what the governor is trying to do is make it agnostic enough that when Gateway does get approved, you can bolt it on regardless of where you are within the time frame of the projects that he announced,” he added.

Industry allies

As far back as 2012, less than two years into his first term, the governor’s air travel was provided by real estate donors.

To be more precise, he used private jets provided by SL Green Realty and developer John Catsimatidis (another Trump pal) to ping-pong to various fundraisers, the New York Daily News reported at the time.

Around the same time, real estate players were also flying high with a major policy victory courtesy of Cuomo and the state: the renewal of 421a, the billion-dollar annual tax break. The governor had signed the tax exemption into law the previous year. (He did so again in 2017 under its new name, Affordable New York.)

But while Cuomo’s mutually beneficial relationship with the industry is not new, keeping that relationship strong is as important as ever. That fact is not lost on the industry, which has given more money to Cuomo than to any other candidate for governor in state history.

In the first six months of 2018 alone, Cuomo’s re-election campaign took in more than $730,000 from New York-based real estate executives and their LLCs. That includes the LeFrak family, the Durst Organization, Extell’s Gary Barnett and Brookfield.

And it’s not surprising that many of Cuomo’s top donors are often those with significant business before the state.

Brookfield — which has given Cuomo more than $1.2 million since his first term — relied on state tax-exempt bonds for the construction of the Eugene, an 844-unit luxury rental tower in Midtown West, where it also negotiated with the state-run MTA. It also took a slice of a $175 million state subsidy that funded its hydroelectric facility in Oswego County in 2015 and a $360 million incentive last year that included two of its other facilities. The company did not respond to requests for comment.

Other developers are also taking advantage of Cuomo-backed incentives outside the city.

Seth Pinsky, of RXR Realty — another Cuomo donor, which has big mixed-use development projects in Westchester and on Long Island in addition to Manhattan — praised the Cuomo administration for incentivizing more density in suburban downtowns with $10 million investments for plans in qualifying locations.

“If we’re going to make the region more affordable, it’s also about just increasing the supply and density of housing,” said Pinsky, former president of the New York City Economic Development Corporation.

Cuomo could also play a key role in other areas that are important to New York City real estate. And the governor’s positions on those points are less clear.

For example, the governor is stuck between two feuding political allies — New York City’s biggest developers and the powerful construction trades — on the contentious topic of union labor. And both sides will likely be courting Cuomo for support.

Gary LaBarbera, president of Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, said that “the governor is extremely supportive of using union trades on state projects, and his track record reflects this.”

The governor may also find himself caught between a host of other issues involving unions and developers, ranging from the Scaffold Law to the Wicks Law, where millions of dollars are on the line for both sides. “I think the question of unions and work rules, and how unions are working on large projects, is going to be a focus,” said Ward, who stepped down from AECOM last month. “I think there’s a day of reckoning coming about how that gets resolved.”

Cuomo has, however, punted on similar issues in the past.

In 2015, when the state was negotiating the renewal of 421a, Cuomo pitted labor groups against the real estate industry, forcing the two to hash out the final terms of a deal. That process ended up dragging on for close to two years.

But given Cuomo’s political ambitions and his tack to the left during his primary campaign, there’s no telling which issues he’ll tackle, who he’ll side with — or if he’ll remain out of the fray.

“Cuomo has been preparing for this for a long time,” said Ken Fisher, a government affairs attorney with Cozen O’Connor who represents developer clients. “I believe he was headed in that [leftward] direction because he’s been planning on running against Donald Trump since 2017.”

Conditional cash

After signing an emergency declaration for the New York City Housing Authority in April, Cuomo told reporters that “government does not build well. It’s not what we do.”

“Get a private sector contractor to do it, give them the money and get out of the way,” he said.

While that sounds like it could be a boon for developers specializing in affordable housing, there’s no clear public indication of how — or when — that money will be spent.

In the case of NYCHA — which oversees more than 175,000 apartments in the five boroughs — the administration has flaunted generous funding promises, while also reminding everyone that it’s not required to provide state money in the first place.

In the case of NYCHA — which oversees more than 175,000 apartments in the five boroughs — the administration has flaunted generous funding promises, while also reminding everyone that it’s not required to provide state money in the first place.

Cuomo’s housing commissioner, RuthAnne Visnauskas, and other administration officials have been quick to note that funding the embattled housing authority is primarily the federal government’s responsibility.

Prior to this year, the administration had earmarked $300 million over the course of several budgets. But that money is still sitting largely unspent. The governor added another $250 million in April and has said he would only release the money on one condition: that a state-appointed monitor be put in place to oversee the spending.

Then, when federal prosecutors ordered their own monitor to oversee a $1 billion settlement with NYCHA in May, Cuomo pulled his plan for a state monitor and said he would instead release the funds once the federal monitor was appointed. That has yet to happen.

The budget director, Mujica, noted that NYCHA has a history of misspending. “It’s not something that any private sector builder would tolerate in any one of their buildings, so it should not be tolerated in public housing, either,” he said. “That’s why you put a condition on it. We want to make sure that whatever money we give them is managed and used properly.”

Cuomo also added a condition to $2 billion in funding for a big supportive housing plan he announced as part of his annual budget in 2016. Once his budget passed, the governor said the funds could only be disbursed after a “memorandum of understanding” was struck between him and state legislative leaders — the full terms of which were never made public.

“That was contrived for political leverage,” said Shelly Nortz, deputy executive director for policy at the nonprofit Coalition for the Homeless, which relentlessly lobbied the state on this issue. “It was really maddening, because it made people think there was some kind of mechanical obstacle that wasn’t real.”

Others say Cuomo has done virtually everything in his power to publicly finance the creation and preservation of more affordable housing.

Rachel Fee, executive director of the affordable housing group New York Housing Conference, said she wants the governor to pledge more capital to NYCHA but commended him for his $20 billion affordable housing plan. The initiative — the first of its kind in New York state — has already set aside $2.5 billion to build or preserve 110,000 units statewide.

“New York state had housing finance programs, but they didn’t have a housing plan,” Fee said. “When the governor’s plan was funded, it doubled the capital commitment that we had seen in the past.”

Fee said the administration has also been innovative with allocating tax-deductible bonds to help finance the first so-called Rental Assistance Demonstration conversion, which turns badly deteriorating public housing into privately managed rentals that accept Section 8 vouchers.

The money for that project — RDC Development’s 1,395-unit Ocean Bay Apartments in Far Rockaway — included $213 million in state housing bonds.

And for the developers who’ve carved out a niche in affordable housing — RDC, L+M and Camber Property Group, to name a few — any third-term investment by Cuomo in this space could mean another round of projects to capitalize on.

Rick Gropper, a Camber principal and former development director at L+M, noted that on Cuomo’s watch there’s been a greater emphasis on ensuring that affordable housing doesn’t get lost to the market-rate world.

“The state actually very recently hired its first chief preservation officer,” he said.

James Rubin, who served as Cuomo’s housing commissioner from 2015 to 2017, said the administration “didn’t start at the back and work our way down” on affordable housing.

“We basically said, ‘What do we think our reasonable level, or aggressive level, of resources could be over next 10 years, and how can we stretch that as far as we possibly can?’” he said.

Robert Moses 2.0?

Whether Cuomo lives up to the real estate industry’s expectations, how he navigates the changes afoot in Albany in his third term remains to be seen.

Infrastructure is an easy target in many ways. Baruch’s Birdsell called it a “consensus” policy — one both political parties (at least in theory) agree on pursuing.

“Andrew Cuomo can come in, very credibly, and say that ‘I have a reputation of getting things done,’ he said. “And that’s more or less true.”

But whether the governor goes down as a master builder in the five boroughs may largely depend on how much capital he can squeeze out of Washington to get those projects out of the ground.

His record on all of it will not only go down in the state’s history books but will also play into how Cuomo can cast his record if he does, in fact, make a bid for the White House.

RXR’s Pinsky, for one, commended the governor for cleaning house and notching some big accomplishments.

“When Gov. Cuomo came into office, New York state government was characterized by complete and total dysfunction,” Pinsky said. “I think the governor deserves credit for the significant additional investment that he’s making.”

Meridian Capital Group’s David Schechtman also praised Cuomo’s efforts.

“The governor is a real New Yorker keen on accomplishing Robert Moses 2.0,” he said. “The Tappan Zee and continuation of massive projects like Hudson Yards and Essex Crossing are a testament to his focus on transportation issues.”

That is no doubt a sales pitch Cuomo would like to take to the American people. But first he’ll have to “strike a balance” with the demands of the new left-leaning Democrats in Albany and his real estate base, said Cozen O’Connor’s Fisher.

Ultimately, Fisher said, Cuomo is not going to turn his back on the industry — which not only generously fills his campaign coffers with cash, but also acts as an economic engine for the city and state.

“He’s not gonna kill the goose that lays the golden egg,” he said.