Nicholas Mastroianni II is a man in perpetual motion.

Nicholas Mastroianni II is a man in perpetual motion.

The 52-year-old CEO of the U.S. Immigration Fund, which raises money from foreign investors for real estate developments through the EB-5 program, spends a considerable chunk of his time on the road.

Last month, that meant a 10-day trip to China, Korea and Vietnam — which partly explains why, in the middle of that trip, after several attempts to connect, he emailed to suggest a phone call at 11 p.m. Korea time.

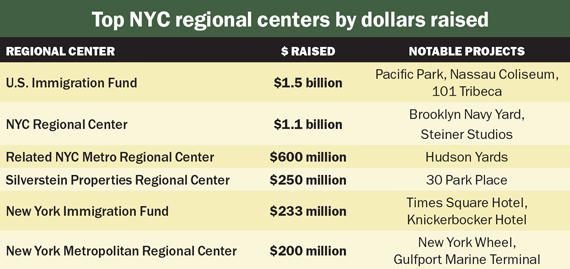

“I’m all over the world, that’s the problem,” he chuckled. “I’m in South Korea now.” Since 2010, when Mastroianni got into the EB-5 business, he’s lined up more than $1.5 billion from EB-5 investors, who chip in $500,000 each in exchange for a U.S. green card. Ninety percent of USIF’s clients are major New York real estate players, including Forest City Ratner, the Durst Organization, the Witkoff Group, HFZ Capital and Kushner Companies. Having arranged financing for mega-projects like Pacific Park (formerly known as Atlantic Yards), along with more than 20 other office and condo projects, USIF is the largest regional center in New York — if not the country.

Regional centers, otherwise known as “sponsors” of EB-5 projects, are the intermediaries between developers and investors — acting as de facto clearinghouses for immigration documents and investor capital.

But the central role regional centers have taken on has emerged as a major flash point for criticism of EB-5, which has garnered a reputation for being opaque, not to mention rife with fraud. In addition, the program has incited anger among some who say it spurs economic investment in urban areas while turning a blind eye to the rural parts of the country that truly need it.

Michael Gibson — managing director of USAdvisors, a registered investment advisory firm that does EB-5 due diligence work — called the industry “broken” and pointed the finger at U.S. Citizen and Immigration Service, the division within the Department of Homeland Security that oversees the program and regulates regional centers.

“This is a great program if it’s done right, but the biggest problem is transparency,” said Gibson, who also consults for developers and sometimes regional centers.

While Congressional efforts to reform the industry fell flat this fall, stakeholders are bracing for changes before EB-5 comes up for renewal again on Sept. 30. And many of those reforms are expected to target regional centers.

But the development and real estate finance communities have made no bones about the fact that they are staunchly behind these regional centers.

Case in point: When Howard Michaels of the financial intermediary the Carlton Group introduced Michael Shvo to USIF back in 2014, he urged the developer, who was trying to line up financing for 125 Greenwich, a 275-unit condo, to “sign them up” quickly.

Source: Research by NYC professors Jeanne Calderon and Gary Friedland, TRD and EB-5Projects.com

In an email to Shvo, Michaels cited USIF’s successful fundraising on behalf of New York clients like the Witkoff Group. “According to the Witkoff Group,” Michaels wrote, “they put on an unbelievable show.”

Profit powerhouses

When Mastroianni launched USIF in 2011, EB-5 was still in its infancy, with only 28 regional centers nationwide.

Today, there are more than 800, and at least 65 of them call New York home.

And while developers and investors are not required to use these regional centers, the vast majority of EB-5 capital — some 95 percent — flows through them.

In fiscal year 2015, EB-5 accounted for $4.38 billion in direct foreign investment in the U.S. — up from $3.56 billion a year earlier and from only $320 million back in 2008, according to the Regional Center Business Journal, a quarterly trade publication.

Although some developers like the Related Companies and Silverstein Properties have in-house regional centers, most developers use a third party to avoid the expense and logistics of complying with federal requirements.

“The regional center is a point of communication between us and the investors,” said Asaf Schuster, vice president of business development for Victor Group, which, along with Lend Lease, is raising $90 million for a 55-story condo at 281 Fifth Avenue. Victor Group has tapped the Manhattan-based American Immigration Group as its regional center.

Not surprisingly, regional centers get paid generously for acting as the conduit between developers and investors.

Developers typically pay regional centers between 5 percent and 8 percent of the total capital raised. (A back-of-the-envelope calculation based on those percentages shows that Related, which raised $600 million in EB-5 cash for its giant Hudson Yards project, may have saved around $50 million by setting up its own regional center.)

In addition to that percentage haul, regional centers also charge each investor an administrative fee of $25,000 to $60,000 on top of the $500,000 minimum commitment they are making to the project. A $100 million raise, therefore, would generate fees up to $8 million from the developer and up to $12 million from investors.

Those aren’t pure profits, of course. But at $200,000, the cost of setting up a regional center is paltry, especially because developers also pay for things like marketing materials, business plans and economic studies that must be completed to ensure that every project complies with USCIS requirements. Each $500,000 investment must also create 10 jobs, and it’s up to regional centers to document that a project meets those criteria.

Nick Mastroianni

Lately, regional centers have also been shelling out big money to hire foreign “migration agents” who line up investors. (See related story on page 56.)

Min Chan, a co-founder of the regional center launched by the Manhattan-based brokerage City Connections, said she recently interviewed a migration agent who wanted $25,000 up front — plus up to 4 percent of the capital raise.

“The whole point of EB-5 is more affordable capital,” she said. “If you’re taking 3 to 4 percent of what we raise, and the investor gets [a standard] 1 percent, what’s the regional center going to keep?”

The snowball effect

Mastroianni has a beefy build, black-and-silver hair and the perpetual suntan of someone who spends a lot of time on golf courses.

A Long Island native, he moved to Palm Beach in the ‘90s and now splits his time between homes in Florida and Manhattan when he’s not racking up international frequent flier miles.

Rewinding a few decades, Mastroianni got into the construction business at age 19. In 1989, he started a Rhode Island-based company, Interstate Design & Construction, which soundproofed buildings near airports. Then in 2004, he launched the Florida-based Allied Capital & Development.

However, it has not all been smooth sailing. In 2014, a published report documented a series of debts and lawsuits that the young entrepreneur left in his wake over construction issues.

According to the story, Interstate went into receivership in 2000. Mastroianni filed for personal bankruptcy in 2003.

“Listen, when you’re on top, people want to knock you down,” Mastroianni said recently, when asked about the article. “It stems from people who are jealous and envious of what we do.”

Reflecting a bit more, he said life takes winding roads. “If I didn’t do all the things I’ve done in life, I wouldn’t be here today,” he said. “I might be banging nails on roof shingles, like when I was 19.”

Instead, in the mid-2000s, years before EB-5’s skyrocketing popularity — the program has actually been on the books since 1990 — Mastroianni used the little-known program to finance a mixed-used development of his own in Jupiter, Fla., a wealthy enclave near Palm Beach.

Mastroianni was trying to line up financing for a $144 million project called Harbourside Place. “There was no way to finance the project,” he recalled.

In 2010, after learning about EB-5, he formed the Florida Regional Center to raise nearly $100 million from Chinese investors.

“I said to myself, ‘If I can pull this together, I have 10 friends in New York who would love to borrow this inexpensive mezzanine capital, too,’” he said.

The following year, Mastroianni landed his first New York City project when he was hired to raise $23 million for the Charles, a 27-unit luxury condo developed by Bluerock Real Estate and Victor Homes. From there, the newly formed U.S. Immigration Fund was hired by Forest City, Durst and others. “It snowballed,” Mastroianni said of USIF’s growth. “We were successful in putting together projects. It’s not like a back office, fly-by-night operation.”

In 2014, he was doing well enough to shell out $3.8 million for a penthouse condo at 230 East 63rd Street, according to public records. Today he is currently raising $800 million for various projects, Mastroianni said.

Asked how he connected with those early, marquee clients, Mastroianni cited Wallace Stevens’ poem starting with the phrase “After the final no there comes a yes.”

Nassau Collseum rendering

He added: “It’s really about persistence and determination. I wanted to be successful. I made it my mission to find out who was in the industry and how to get to that point.”

Six years on, Mastroianni said USIF has thrived because it “institutionalized” the EB-5 business — previously thought of as second-rate financing — by employing securities and immigration attorneys, performing due diligence and maintaining strict compliance with regulatory statutes. USIF has 40 employees in the U.S., 18 in China and 10 in Mexico, India, Korea and Vietnam.

In New York circles, Mastroianni is often accompanied by Vivian Ding of GDOS — one of China’s largest migration agencies.

While Ding lines up investors, Mastroianni’s handles business development — in other words, forming and reinforcing partnerships and spreading the gospel of USIF.

A 2014 term sheet between USIF and Shvo offers a glimpse into just how much USIF’s services cost. For $300,000, USIF conducted economic studies, drew up immigration documents and produced a slick promotional video. Shvo also footed the bill for two 10-day trips to China for four members of USIF’s team along with a developer’s representative.

Regional center rivals

While USIF is the largest regional center in New York, it’s certainly not alone.

New York Regional Center, co-founded by real estate attorney George Olsen and Paul Levinsohn — who served as chief counsel to former New Jersey Gov. Jim McGreevey — is also big.

NYRC, which opened its doors in the throes of the financial crisis in 2008, has since raised more than $1.1 billion in EB-5 capital. Projects include the Brooklyn Navy Yard ($60 million), Steiner Studios ($145 million) and 215 Chrystie Street ($80 million), the 11-unit condo developed being developed by Witkoff and hotelier Ian Schrager.

Other regional centers have popped up in a remarkably short period of time.

The Manhattan-based American Regional Center for Entrepreneurs, for example, launched in 2013 and has since raised $50 million for Xin Development’s Oosten, a 216-unit condo in Williamsburg. It is currently raising another $50 million for China Vanke and RFR’s condo tower at 100 East 53rd Street.

EB-5’s popularity has created competition among regional centers, who fiercely guard the identities of their foreign contacts. Migration agents and investors, too, want to see a strong financial commitment from the developer, said Jacqueline Finkelstein, principal and COO of the American Immigration Group.

The center is raising $75 million for a condo project at 45 Broad Street and $100 million for the redevelopment of the Kingsbridge Armory in the Bronx, which is being turned into a nine-rink ice-skating complex.

“If you show less than 20 percent [developer equity], most of the good [migration agents] will run for the hills,” she said.

Where are the watchdogs?

Over the last six years, Mastroianni has demonstrated an unrivaled ability to woo developers and investors. But not everyone appreciates his sharp-elbowed style.

He was sued in 2011 and 2013 by former partners. In 2015, USIF’s former CFO, David Finkelstein, accused Mastroianni of financial improprieties. Finkelstein’s accusation came in the form of counterclaims to a 2014 lawsuit filed by Mastroianni, in which he disputed Finkelstein’s ownership stake in their Florida-based EB-5 business. Mastroianni told TRD that the case against Finkelstein is settled.

Finkelstein — Jacqueline Finkelstein’s father — is now working for the competition as president and CEO of the American Immigration Group.

Jacqueline Finkelstein (Photo by Larry Ford)

If they are aware of Mastroianni’s past financial and legal woes, USIF’s clients have not batted an eye.

“Nick got us our money and got the job done,” said an executive at one of the city’s major development firms.

Hudson Companies’ David Kramer said he considered several regional centers before going with USIF to raise up to $110 million for the redevelopment of the Brooklyn Public Library at 280 Cadman Plaza, which will include a new library at the base of a 139-unit condo tower as well as 114 affordable units at two nearby sites

“We did our due diligence and went in with eyes wide open,” Kramer said. “You have to make judgment calls and I have absolute confidence in his ability to perform. … It was a big deal for us that he had a track record.”

Attorney Eric Orenstein of Rosenberg & Estis, who works exclusively with Mastroianni’s USIF on EB-5 deals, said the regional center is one of the few closing deals.

“There are a lot of people running around claiming, ‘I’m a regional center and I’m going to raise this money for you,’ and they’ve never raised a dollar,” he said.

But therein lies one of the most frequent critiques of EB-5 overall — that it’s an industry lacking oversight and accountability.

As far back as 2013, the Office of the Inspector General, which is charged with weeding out waste and abuse in the federal government, reported that USCIS lacked the authority to crack down on fraud.

“The only watchdog in this is the SEC,” USAdvisors’ Gibson said, “and they’re cleaning up the mess long after the house was put on fire.”

Coming into compliance

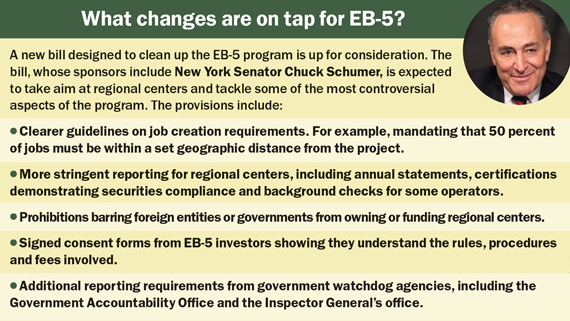

With criticism of EB-5 mounting, Congress grappled with potential changes to the industry this past fall.

U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein went as far as calling for an end to EB-5 altogether.

“The EB-5 regional center program sends a message that American citizenship is for sale, and [it] is characterized by frequent fraud and abuse,” the California Democrat wrote in an Op-Ed published in the Capitol Hill newspaper Roll Call.

Industry sources said there’s now widespread recognition that any reform will target regional centers.

“Regional centers will look more like compliance offices,” said Manhattan-based attorney Clem Turner of Homeier & Law, speaking at an EB-5 conference organized by financial firm NES Financial last month.

Attorney Jennifer Moseley, a partner at North Carolina-based Morris, Manning & Martin LLP who represents regional centers, told TRD she regularly gets calls from centers that want to clean up their act.

While Moseley said she’s helped bring centers into compliance, she noted that “there are things from a securities perspective that are unfixable.” For example, some may have marketed projects in a way that inadvertently constituted a public offering, such as advertising in the U.S. to potential investors.

While Moseley said she’s helped bring centers into compliance, she noted that “there are things from a securities perspective that are unfixable.” For example, some may have marketed projects in a way that inadvertently constituted a public offering, such as advertising in the U.S. to potential investors.

In 2015, the Government Accountability Office, a congressional watchdog, exposed vulnerabilities in how the EB-5 program is run, specifically the inability to vet where investors’ money is coming from. Its report found that USCIS does not consistently enter information it collects on participants, creating barriers to conducting electronic searches that “could be analyzed for potential fraud.”

But a more complete data-collection system is four years behind schedule — and $1 billion over budget.

Despite renewed calls for reform, Congress reauthorized the EB-5 program in December with no changes. But it’s likely to revisit those reforms before the next reauthorization in September.

The last round of proposed changes would have raised the minimum investment threshold (the program is among the cheapest of its kind worldwide) and instituted more stringent due diligence, among other reforms.

For his part, Mastroianni chalked up USCIS’ shortcomings to a lack of resources.

“The program has grown so much that it’s overburdened,” he said.

But he said he was “all for” improving EB-5, including additional oversight and transparency for regional centers like his. In particular, he said he supports increasing the minimum financial contribution from investors, charging additional fees for large families and setting aside a certain number of visas each year to be used in impoverished areas.

Recalling how his grandparents immigrated to New York from Italy, Mastroianni

said the bottom line is that EB-5 is both an immigration program and an economic

stimulator.

“We’re creating American jobs through foreign investment, without taxing you and I,” he said. “It’s a fantastic thing.”