Between April and June, when the pandemic went from a shocking jolt to a daily reality, a record number of people fell behind on their home loans.

Between April and June, when the pandemic went from a shocking jolt to a daily reality, a record number of people fell behind on their home loans.

“The Covid-19 pandemic’s effect on homeowners’ ability to make their mortgage payments could not be more apparent,” said Marina Walsh of the Mortgage Bankers Association, noting that the second quarter had the highest overall delinquency rates in nine years.

It was a worrying trend, particularly given that the country had about $16 trillion in outstanding residential and commercial mortgage debt with more than 60 percent of that bundled into securitized home loans. But it was hardly surprising: Millions of people were out of work, virus cases were surging, and political infighting was hampering efforts to lock in another stimulus bill.

For most people, hearing the words “mortgage” and “crisis” in the same sentence evokes memories of the last economic collapse, brought on when the housing bubble burst after years of risky lending, causing a credit crunch that hobbled the global economy for years.

Now, with interest rates low and employees working remotely, many Americans are rushing to buy homes. But a repeat of 2007 is unlikely.

This time around, the government has injected more stimulus money into the U.S. economy, struggling homeowners have been given mortgage forbearance and a tight supply of housing has driven up home prices across the country.

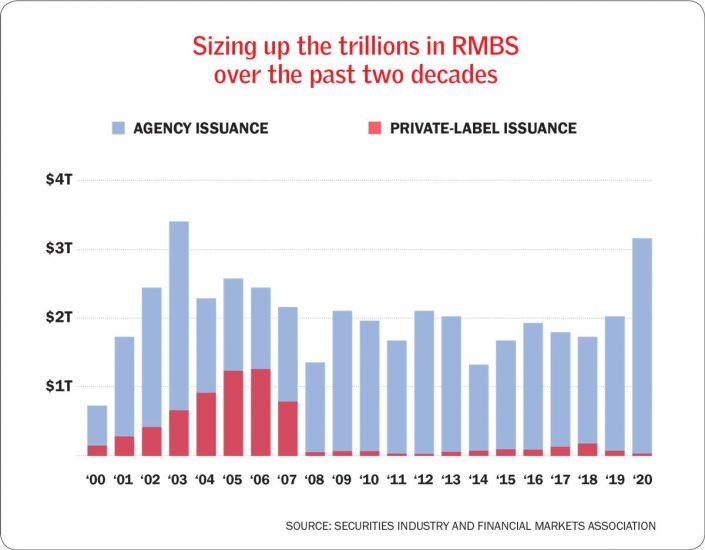

Mortgage-backed securities — central to the last crisis — are also under much tighter controls, and the once-booming private RMBS market has been eclipsed by government-backed offerings.

Though there was a small bump in private issuance between 2015 and 2018, that momentum was slowed by the pandemic, and moves to reduce government dominance in the wider market have grown more uncertain with the election of Joe Biden as president.

“Unless the government steps away in a big way from the mortgage market, I don’t see that there will be any room for the private RMBS market,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics.

Then to now

Then to now

The securities, in simple terms, are pools of residential mortgages bundled into bondlike instruments, which are backed by interest payments from homeowners and sold off to investors — making RMBS deals susceptible to foreclosures and personal bankruptcies.

For many years, the country’s housing market has been backed by both agency RMBS, issued by government-sponsored entities such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and the “private-label” offerings securitized by banks and other private lenders.

In the years leading up to the last crisis, the markets for both private and agency RMBS had started to fill up with loans issued to people with poor credit scores, no documentation and other red flags. That included homeowners and speculators who were looking to buy up mansions which, despite relatively high incomes, some just couldn’t afford.

Banks that had been busy making money from these securities were later accused of not doing enough due diligence about the quality of the mortgages inside them and failing to see that the market was a house of cards. (Or, as famously immortalized by Ryan Gosling in “The Big Short,” a Jenga tower.)

Whatever image you prefer, the whole thing collapsed spectacularly.

The market today looks a lot different. Property values are strong in most parts of the country, and the latest crisis has been fueled by a virus rather than reckless mortgage lending.

Perhaps most importantly, the amount of private RMBS issued in recent years is a fraction of what it was in 2006 and 2007, when it topped more than $1 trillion.

Private issuance now makes up only 1 percent of the market compared to the other 99 percent of agency RMBS, according to recent figures from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA). Before 2008, the two were almost tied.

To Zandi, comparing the private market then to now is “night and day,” in part because of all the regulations that were put in place after the economy collapsed.

“The mortgages that are being securitized these days are much better underwritten,” he said. “There’s no such thing as ‘no-doc loans’; the underlying credit characteristics of the borrowers are very different; and the rating agencies now have to do their own due diligence on the loans that go into the securities.”

Zandi said the size and structure of the private RMBS market means the risks in that area are low — even if we see deeper distress set in.

“If things went off the rails for housing and house prices started to decline, I’m sure you’d see some credit issues,” he said. But, he added, they would be “modest.”

Homebound in 2020

With private RMBS reduced to a bit player, agency RMBS is surging ahead as its more popular sibling: Last year, $1.99 trillion was issued, according to SIFMA. So far this year, that number is up to $3.19 trillion.

Thanks in part to low interest rates and robust federal support for the economy, demand for single-family homes also increased in 2020 as inventory fell, pushing prices higher. According to JPMorgan, home ownership is up 4 percent from last year.

Still, glaring inequalities have also been exacerbated by the pandemic.

“For all the excitement around the housing market, you’ve got a significant share of the ownership population — and it’s skewed toward disadvantaged or underserved communities — where they are simply not able to make their mortgage payments,” said Sam Chandan, dean of New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate.

After the pandemic hit, the government extended forbearance to homeowners with federally backed mortgages who were struggling to meet their repayments.

The move mostly stopped foreclosures, though some markets saw an uptick this fall and many anticipate a larger wave in the upcoming year.

In the second quarter, almost 16 percent of home loans backed by the Federal Housing Administration were delinquent, the highest rate in four decades. (The Federal Housing Administration, part of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, is not to be confused with the Federal Housing Finance Agency, which regulates Fannie and Freddie.)

By November, some 2.74 million home loans were in active forbearance — a drop from the week prior, according to data firm Black Knight. The total represented 9.1 percent of Federal Housing Administration/Veterans Affairs loans; 3.5 percent of Fannie and Freddie loans; and 5 percent of “other” loans, including those held in private-label securities.

“I don’t think [the delinquencies] are going to present a major financial challenge to the GSEs,” said Edward Pinto, director of the Washington, D.C.-based think tank AEI Housing Center, noting that the most serious delinquencies are concentrated in FHA loans.

“That said,” Pinto added, “it is going to cost them some numbers of billions of dollars,” which is one of the reasons the Federal Housing Finance Agency raised its fee for homeowners looking to refinance, a measure due to come into effect in December.

In 2008, widespread foreclosures and a severe pullback on mortgage lending sent housing values tumbling, putting a dent in the national homeownership rate.

“This recession is different,” said Mike Fratantoni of the Mortgage Bankers Association. “As a result of the pandemic and the lockdowns that were meant to control it, we saw an extraordinarily sharp drop in the level of economic activity in spring, and then a very rapid rebound, particularly in the housing sector, as states began to reopen beginning in May.”

Forecasts for 2021

Forecasts for 2021

When Biden assumes the presidency in January — a likely outcome to the election despite a slew of legal challenges from Donald Trump — he will be tasked with sorting out an issue that has befuddled several administrations past: what to do about Fannie and Freddie.

When the Federal Housing Finance Agency took control of the mortgage giants after the last crash, few imagined the conservatorship arrangement would last 12 years.

But the path out is complicated, and the announcement in November that Freddie Mac CEO David Brickman would be stepping down has only clouded matters more.

“The Biden administration will not be in a rush,” said Mark Willis, senior policy fellow at the New York University’s Furman Center. “And the best reason is, [the mortgage market] is not broken.”

Though a lot has changed since 2008, one thing that hasn’t, even with more government involvement in the RMBS market, is the hefty profits made by lenders.

In the first half of 2018, global banks made just under $200 million in revenues from agency RMBS, according to research house Coalition. By 2019, that number reached $1 billion.

In the event that the government steps back and private RMBS does make a comeback, the market will have a different cast of players than it did in 2008.

Back then, nonbank lenders like Countrywide — once referred to by former CEO Angelo Mozilo as his “baby” — were called out as major culprits. After everything fell apart, Countrywide and others were swallowed up by big banks, while others fizzled out altogether.

Tom Schopflocher, a senior director at S&P Global Ratings, said the most active issuers today include Wells Fargo, J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs and Credit Suisse.

“The big banks on the list were around prior to the global financial crisis,” he said.

“But many of the originators and issuers from that time are long gone.”