There are figurative cutthroat businesses, and there are literal ones. Yitzchak Tessler knows the difference.

Chain-smoking in his Midtown office, he recalled his days flying from South Africa into civil war-torn Angola to buy gemstones. In the 1980s, “blood diamond” hadn’t yet become a rallying cry for human-rights groups, and traders could work in war zones with impunity. The country’s capital, Luanda, was a woebegone place — sewage in the streets, no running water in his hotel. Some nights, Tessler would lie awake hearing gunfire for hours.

“You know, in those places a human life is zero,” he said. “It’s like the ash in this ashtray.”

After losing his father at 14, Tessler had to help support his family and found a cleaning job at a diamond cutting factory in his native Israel. Diamonds have a tendency to pop out of tweezers; an observant cleaner can quite easily pocket a few small stones hiding in the floor. Tessler, though, said he always returned any gems he found, earning him the bosses’ trust.

“Either they liked me, or they felt sorry for me because I was an orphan,” said Tessler, a rotund, bearded man who always looks like he’s about to tell an inappropriate joke. “But either way, they started teaching me how to polish diamonds.”

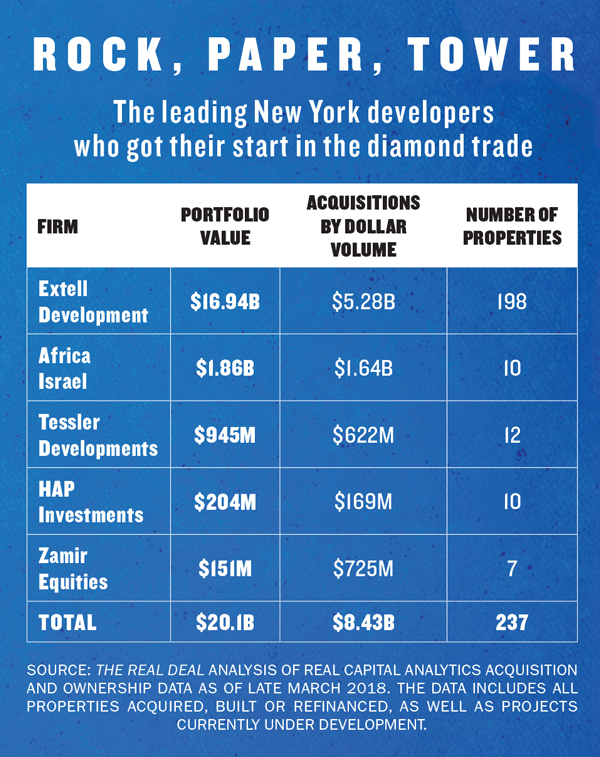

Tessler’s career took him from that factory in Tel Aviv to his own enterprise in Johannesburg, the industry’s epicenter in Antwerp, its buying hub in London and its upstart market in Moscow. And finally to Manhattan, where he decided to tackle another luxury product: condominiums. His journey epitomizes the global gem trade’s deep ties to New York’s real estate industry, which is filled with many who cut their teeth cutting diamonds. Among them are Gary Barnett of Extell Development, Lev Leviev of Africa Israel, Eran Polack of HAP Investments and Asher Zamir of Zamir Equities. The skills needed to turn a rough diamond into a coveted luxury good, experts say, come in handy when transforming a patch of dirt into a high-end residence.

Between them, developers who began in the diamond trade have built, acquired or have an interest in over 200 properties and projects now worth at least $20 billion, according to an analysis of Real Capital Analytics by The Real Deal. And then there’s the broader influence diamond money has on the market — entities tied to Manhattan’s Diamond District own at least 259 properties in New York City, an analysis of property records shows. Investors from the global diamond industry have been major backers of Ziel Feldman’s HFZ Capital Group, Kushner Companies and many other top developers. Their contributions tend to be buried behind a maze of LLCs, frontmen and limited partnerships.

In most cases, the investments are legitimate. Sometimes, they aren’t. Gemstones are a popular tool to launder money, experts said, and real estate often provides the final rinse.

As one of the world’s alpha cities, New York attracts wealth from all backgrounds and industries to its real estate market. But it’s hard to think of another business that’s as intertwined with the industry as the diamond trade. TRD set out to trace how this opaque, underreported symbiosis between diamonds and real estate came about — and how it shaped the skyline.

“The diamond business is a cash business,” Tessler said. “So diamond people — the successful ones, at least — always have cash. And developers don’t have cash. So they all came in one way or another.”

The American

In 1980, while holidaying in Florida, Gary Barnett met Evelyn Muller, the daughter of a prominent Antwerp-based diamond dealer. The two wed, and Barnett was invited by her father, Shulim Muller, into the family business, S. Muller & Sons. He spent a decade in Belgium learning the craft and led the Mullers expansion into the U.S., which is today the world’s largest diamond market.

“He developed the American market for us,” Jean Claude Muller, one of Shulim’s sons and current CEO of the firm, told New York magazine.

Yitzchak Tessler

Barnett helped the Mullers and other Belgian diamond families diversify, moving back stateside to invest their money in U.S. real estate. For a time, he partnered on projects with Feldman and Kevin Maloney. “We had a little tiny office with no heat and Home Depot card tables for desks,” Maloney has said of that period. “We were just guys cobbling deals together, begging and borrowing to try to get deals closed.”

After starting with Midwest shopping malls, Barnett made his first splash in New York with the 1994 purchase of the Belnord, a luxury rental on the Upper West Side.

“[The Belnord] was like a 100-carat diamond in the rough,” Barnett reportedly recalled telling his Belgian investors.

While Barnett was putting together the foundations of his real estate empire, Serge Muller, another son of Shulim’s who had worked alongside Barnett in the family business in Antwerp, took a different path.

Serge had gotten involved in diamond mining in Sierra Leone and played a cameo in the West African country’s brutal civil war: In 1998, the ruling party’s sole combat helicopter broke down just as it was facing a surprise offensive from the Revolutionary United Front, a rebel group infamous for chopping off its enemies’ limbs. Serge reportedly agreed to provide the government a new engine and ammunition for $3.8 million. Ben Holemans, CFO of Serge’s company, Rex Mining Corporation, would tell shareholders that Serge “has close friends in all political factions of both government and RUF.” Serge went on to build a career in arms trading, and in 2015 was arrested in Montenegro on charges of laundering money for drug traffickers and extradited to Belgium.

There don’t appear to be any ties between Serge and Barnett’s real estate business. Evelyn died in 1998, and a source close to the developer said the Muller family has not invested in his projects in decades. Barnett declined several requests to comment for this story.

But Isaac Mostovicz, who married into the Muller family and served as S. Muller & Sons’ CEO from 1992 to 2006, said the family continued to invest with Barnett after he moved to New York. He described himself as a “small investor” in Barnett’s projects.

“He [Barnett] is part of the family,” Mostovicz said, adding that he occasionally continues to discuss investment opportunities with Barnett. In mid-March, Barnett participated in a Muller family reunion in Israel, according to Mostovicz, who said Serge Muller was also present.

Shortly after the interview, Mostovicz walked back his comments. “No member of the Muller family was or is an investor with Mr. Gary Barnett since he left the family business and left to NY more than twenty years ago,” he wrote in an email.

Barnett gave his firm, Diamond Heritage Properties, a new name: Extell Development. The company’s One57 tower is seen as the building that kicked off this cycle’s ultraluxury condo boom and holds the record for New York’s priciest closed sale, at $100.5 million. Extell also developed the International Gem Tower in the Diamond District, a 35-story building designed to cater to the city’s diamond and jewelry traders. Its latest audacious venture is Central Park Tower, which is projecting a record $4 billion condo sellout.

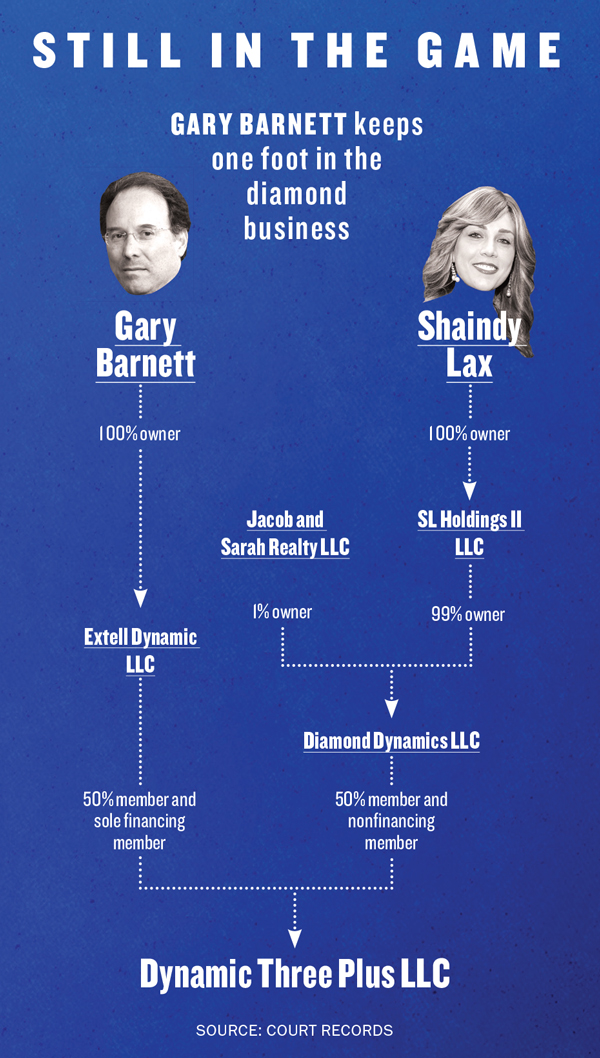

But Barnett never entirely left his old profession behind. In 2015, he co-founded the diamond trading company Three Plus with Moshe Lax, a diamond and real estate entrepreneur best known as Ivanka Trump’s partner in the jewelry business. An entity controlled by Barnett and an entity tied to Lax own the company, whose existence hasn’t been previously reported, in a 50/50 partnership, court records show. Lax declined to comment on the venture.

According to those who’ve done both, diamond trading and real estate share remarkable similarities.

A diamond development cycle starts with the acquisition, often arranged by a broker for a commission. A single rough stone can cost millions, and dealers often fund a purchase by syndicating it with other investors. Some use leverage, borrowing against the stone’s value.

Once you own the rough, you have to figure out what to do with it. Should you polish it into one big gem, or split it up?

“It’s like drawing up architecture plans,” said Lax. Decisions carry risks. Splitting the stone could cause it to shatter, and polishing it can unearth flaws that cause the stone’s value to plummet (a “shlok,” in tradespeak). Giving it a certain shape may put off buyers. And there’s always a chance that the market can turn against you.

In the final stage, polishers put windows into the diamond: small angles that break light and give a gemstone its characteristic sparkle. Then it’s off to a Fifth Avenue storefront. If all goes well, you turned dirt into a luxury asset and made a fortune. If it doesn’t, you may need to answer to your lenders.

“In the mind,” Tessler said of condo development, “it’s not such a big jump.”

The Panther

By 16, Tessler had scraped together $15,000 and struck out on his own. He established connections in Antwerp, the industry’s de facto capital, and by the 1970s was buying millions of dollars’ worth of rough stones a year, either flipping them to other dealers or polishing them for the retail market. In 1978, he moved to Johannesburg and bought a local diamond-cutting factory. That deal led to the industry’s most coveted prize: a seat at De Beers’ table.

At its peak, De Beers controlled 90 percent of the global trade through what it euphemistically called “single-channel marketing.” A cartel of mines would deliver its rough stones exclusively to the company, which sold them to clients at fixed prices.

“If the diamond price weakened, De Beers cut back the flow of goods into the cutting centers,” journalist Matthew Hart wrote in “Diamond.” “When the price recovered, it opened the tap again.” It was De Beers that popularized the expression “diamonds are forever” and made gemstones an essential luxury item.

Ten times a year, diamond traders from Tel Aviv, New York, Antwerp, Mumbai and Hong Kong gathered at the company’s fortress-like London headquarters at Number 17 Charterhouse Street for auctions, dubbed “sights.” The number of sightholders — diamond traders deemed worthy of an invite — was fixed at around 100, meaning those on the inside like Tessler enjoyed the spoils of an immensely profitable private club.

But by the late 1980s, the cartel began to weaken. Prospectors found huge diamond deposits in the Canadian wilderness. Lev Leviev, an Israeli diamond trader born in the Soviet Uzbek Republic to a Bukharan Jewish family, started buying stones directly from Russian mines. Through the Chabad network, Leviev made connections high up in the Soviet government. He needed a partner with diamond-cutting expertise, so he brought on Tessler. In the early 1990s, the two men opened a cutting factory in Moscow. Every Sunday evening for several years, a private plane would fly them there from Antwerp. Every Friday, it would fly them back.

Though Tessler eventually caved to De Beers’ demands and gave up his stake in the Moscow factory, Leviev stood firm. Others followed his lead.

Though Tessler eventually caved to De Beers’ demands and gave up his stake in the Moscow factory, Leviev stood firm. Others followed his lead.

“That’s how Leviev cracked the De Beers cartel,” one merchant told the New York Times. “With the instincts of a tiger and the balls of a panther.”

When in Rome

The cartel’s decline coincided with the rise of low-cost cutting centers in India in the 1990s. Established traders saw their profits dwindle. Looking for alternatives, some turned to New York real estate.

Tessler became a prominent developer by the mid-2000s with a string of successful condo conversion projects such as 241 Church Street and 240 Park Avenue South. But he was hit hard by the financial crisis and was forced to sell 1107 Broadway, which he had bought for $235 million with plans for a condo conversion. He recently developed a 33-story condo project at 172 Madison Avenue.

Others from the trade followed Tessler into the market, and brought with them their customs.

David Schechtman remembers brokering the 2007 sale of a site at 156-160 Leroy Street in the West Village for $34 million. The seller, diamond trader Nissan Perla, hired him but never produced the customary commission agreement.

“Throughout the months that we were working on the deal, not one piece of paper regarding our relationship was exchanged,” Schechtman recalled. “We shook hands. He paid a commission based on a handshake, and I never had any concern.”

The diamond industry’s culture traces its roots to the tight-knit Orthodox Jewish communities of old Europe, sources said. For centuries, Jews were shunned by most trades. Jewelry was an exception, so Jewish traders and cutters came to dominate it simply because they had nowhere else to go. Even as the global trade diversified, Orthodox Judaism continued to be the “unofficial law of the land” in New York’s Diamond District, Alicia Oltuski writes in “Precious Objects,” a book about the city’s diamond trade.

Eran Polack

Traders often share a rabbi and send their children to the same schools. Relationships and reputation are everything.

“The genesis of this is — no pun intended with all these religious guys — the diamond industry started as a very insular, small community,” Schechtman said. “The idea of drafting a piece of paper between these people was insulting.” He went on to represent Aaron Chitrik, another investor from the diamond industry. Again, sans commission agreement.

But that business-by-handshake culture doesn’t preclude disputes. In 2014, Moshe Lax was thrust into a battle with two of Brooklyn’s biggest and most press-shy investors, Abe Mandel and Joseph Brunner. They alleged that Lax had used a series of shell companies to hide the fortune of his late father, Chaim, the founder of diamond trading and real estate investing company Dynamic Diamonds. They also accused Lax of attempting to extort them in order to avoid paying back a loan.

Mandel and Brunner said that before his death, Chaim had taken a $3 million loan that they arranged for him. They guaranteed that loan based on documentation from Chaim that pegged his net worth at $174 million, they claim. The documentation showed that just over $100 million of that money was tied up in real estate. Nearly $50 million was in diamonds.

Lax declined to comment on the dispute.

Another player from the diamond world caught up in legal trouble is HAP’s Polack. In September, an Israeli court ruled that he had lied about being a victim of a $9.5 million diamond heist.

A spokesperson for HAP said Polack is appealing the verdict. The developer has ramped up his activity in recent months, landing a $235 million construction loan for a Chelsea rental project and paying $46 million for a Tribeca condo development site. In an Israeli news broadcast, Dovid Levi, identified as a victim of the diamond theft, said Polack promised to return the money once the insurance paid up.

“Then suddenly,” Levi said, “I hear he’s running around New York, investing in real estate.”

Mazal and Bracha

Along the High Line in a neighborhood once strewn with warehouses and tumbleweeds, Ziel Feldman is building two glassy hotel, condominium and retail towers. Designed by Danish starchitect Bjarke Ingels, the condos at 76 11th Avenue will likely be priced close to $4,000 per square foot.

Feldman’s HFZ paid $870 million for the site in 2015 — one of the most expensive land deals in the city’s history. The project is expected to cost $1.9 billion, and much of the money to bankroll it is foreign: Its $1.25 billion construction loan comes from the Children’s Investment Fund, a British hedge fund, and Chinese investors have put in close to $300 million through the EB-5 cash-for-visas program.

But according to two sources familiar with the arrangement, Feldman had another, previously unreported, backer at the project: Beny Steinmetz, the Israeli diamond magnate.

Renderings of HFZ Capital Group’s “dancing towers” at 76 11th Avenue

HFZ “vigorously denies” any connection to Steinmetz, and so did a representative for Steinmetz. Others involved in the project’s financing declined to comment or said they didn’t know of Steinmetz’s investment. But the two accounts of his involvement were corroborated by two other top executives at big development firms.

The U.S. Justice Department and authorities in three other countries have investigated Steinmetz, head of the mining conglomerate BSG Resources, over allegations that he bribed Guinean officials in 2008 to land mining concessions. In December 2016, he was briefly detained in Israel. Last August, Israeli authorities detained him again, this time on charges including money laundering. Prosecutors said the arrest was part of a probe into “fictitious contracts and deals, among other things in the field of real estate in a foreign country, for the purpose of transferring funds and money laundering.”

The newspaper Haaretz later reported that Romanian authorities indicted Steinmetz on charges of backing an illegal real estate deal in that country.

“We categorically deny any and all allegations of wrongdoing — and note that neither BSGR nor Mr. Steinmetz has ever been indicted by any federal or state authority,” an attorney for Steinmetz said in a statement. “Neither has been tried for any wrongdoing or crime. Neither has been convicted or found guilty or liable for any wrongdoing or crime.”

Tessler remembers first meeting Steinmetz as a youth in Antwerp, where the fourth child of diamond trader Rubin Steinmetz was working with Abraham Laub. Bram, as he was known, was one of the biggest rough-stone traders in Belgium at the time and helped his protégé build a multibillion-dollar fortune.

Steinmetz, Tessler said, “always stuck to the big people.”

Steinmetz reportedly tends to conceal his investments behind a maze of offshore LLCs to which he officially serves as simply an “advisor.”

“He didn’t say, ‘I’m going to build a building or buy some land and develop’,” said one source familiar with Steinmetz, speaking on condition of anonymity. “He backed some very serious developers. He’s been backing them for years.”

People like him, the source added, are “under the radar. They’re allocators.”

Another Steinmetz, Beny’s nephew Raz, seems to share his penchant for secrecy. His company Gaia Investment Corporation (not to be confused with Danny Fishman’s Gaia Real Estate) helped fund Kushner Companies’ $190 million buying spree of a Village-centric multifamily portfolio in 2012 and 2013. Raz’s involvement didn’t become public until last year, following investigations by Bloomberg and the Times. In February 2017, Gaia paid $56 million for a Williamsburg loft building at 475 Kent Avenue. The company’s name did not appear in property records, but a source involved in the deal confirmed its involvement. The property once housed an illegal matzo factory.

Another Steinmetz, Beny’s nephew Raz, seems to share his penchant for secrecy. His company Gaia Investment Corporation (not to be confused with Danny Fishman’s Gaia Real Estate) helped fund Kushner Companies’ $190 million buying spree of a Village-centric multifamily portfolio in 2012 and 2013. Raz’s involvement didn’t become public until last year, following investigations by Bloomberg and the Times. In February 2017, Gaia paid $56 million for a Williamsburg loft building at 475 Kent Avenue. The company’s name did not appear in property records, but a source involved in the deal confirmed its involvement. The property once housed an illegal matzo factory.

In order to understand the influence of those from the diamond trade, TRD attempted to catalog properties owned across New York by Diamond District entities. First, we identified buildings in the area with a high concentration of jewelry businesses. Then, data company Reonomy ran the addresses through its database to find all New York commercial properties owned by LLCs registered to those addresses. We then identified these buildings’ ownership entities and cross-referenced them with public records.

We ended up with 259 properties in the five boroughs whose ownership is directly linked to the Diamond District (see map below). Given how tortuous property investments can be, the real number is likely much higher.

“You have a significant amount of money concentrated basically in a two-to-three-block radius,” said Ed Mermelstein, an attorney who specializes in working with real estate investors from the former Soviet Union. “Like any business in the world, people look to diversify.”

Among the findings: several properties said to be owned by Harlan Berger’s development firm Centaur Properties were registered to the Fifth Avenue office of Rough Diamond Traders, the company now run by Bram Laub’s son, Philippe. Berger and Philippe did not respond to requests for comment.

The Laub-Centaur partnership is developing the Jardim, a $215 million condo project near the High Line. And yet several well-connected industry sources said they had never heard of the Laubs or their property firm, Greyscale Development. Those who knew the family from the diamond business said they weren’t aware of its real estate holdings. One source who has worked with the Laubs on a property deal confirmed that they are active investors but wouldn’t comment further.

New York real estate has always been opaque: Developers frequently syndicate deals with dozens of investors, whose names are kept off the books. This culture makes it easy for people like the Steinmetzs and Laubs to invest a lot of money with little scrutiny. It also attracts money launderers, with diamonds often serving as a conduit.

Say a drug trafficker wants to get his hands on some clean U.S. dollars. He could partner with a gem trader and lend him money to buy rough stones in Antwerp or Tel Aviv. The trader puts millions of dollars worth of stones into a little bag and flies to New York, where he sells them in the Diamond District. The cash he gets in return belongs to the drug trafficker.

“In many cases the jeweler will turn around and say, ‘Hey, I’ve got a good real estate investment for you’,” said one source familiar with money laundering. “So not only is he going to launder the money for him — which means he’ll have good, clean funds in the United States coming from a jeweler — but he’ll put it into real estate.”

“In many cases the jeweler will turn around and say, ‘Hey, I’ve got a good real estate investment for you’,” said one source familiar with money laundering. “So not only is he going to launder the money for him — which means he’ll have good, clean funds in the United States coming from a jeweler — but he’ll put it into real estate.”

I am Sam

Facing the New York Stock Exchange at the corner of Wall and Broad streets is a hulking bunker of a building. Completed in 1913, 23 Wall Street was once the headquarters of J.P. Morgan & Company. In “The Dark Knight Rises,” it represented the exterior of the Gotham City Stock Exchange.

“It’s one of the famous addresses in American capitalism and finance,” Richard Sylla, a financial historian at New York University, told Quartz.

For many years, Leviev’s Africa Israel owned the property. But in November 2008, at the height of the financial crisis, a company controlled by Chinese mogul Sam Pa bought it for $150 million.

Pa, who goes by at least six other names, was born in China in 1958. What he did during his first few decades is unclear. One source told the Financial Times that he worked for the Chinese intelligence service’s external branch in the 1980s.

In the early 2000s, he emerged as a key driver of Chinese investment into Africa. He began with Angola, where after decades of civil war the army had finally defeated Jonas Savimbi’s UNITA rebels. To rebuild the country, the government looked abroad, and Pa, who had connections in Luanda, answered the call with an offer that later became typical of Chinese involvement in the continent: bartering infrastructure investment for oil concessions.

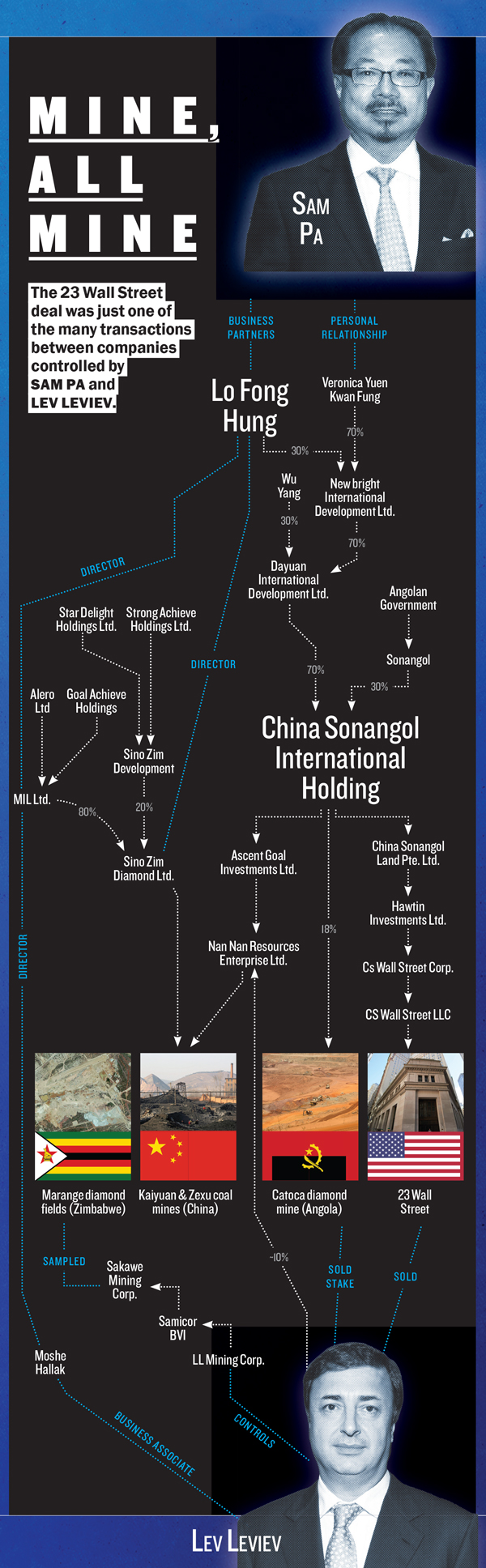

In 2004, Pa and the Angolan government formed a joint venture called China Sonangol International Holding, according to a report by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. A company tied to Pa owned 70 percent of the venture; Angola’s national oil company, Sonangol, owned the rest. At its peak, China Sonangol held stakes in nine different Angolan oil blocks. Meanwhile, an investment fund owned by Pa’s Hong Kong-based group raised $2.9 billion to invest in Angolan infrastructure projects.

Pa had now become a key player in Angola’s oil sector. That meant he was bound to cross paths with Leviev, the alpha dog in the country’s other big export: diamonds.

Leviev first bought a stake in Angola’s largest diamond mine, the Catoca, in 1997 and was on good terms with the country’s president, José Eduardo dos Santos, according to the Times. He urged dos Santos to create a single entity that would control the state’s diamond exports. The president took the advice and rewarded Leviev with a stake in the new venture, Ascorp. In 2006, Pa formed another company, Worldpro Development, that would operate in Angola’s diamond sector, according to the Africa Center report. One of the firm’s directors was an employee of Leviev’s.

The Diamond District in New York City

“When the two biggest natural resources in the country are flowing towards those two counterparties, the two counterparties usually have a vested interest in getting to know one another,” Richard Marin, former CEO of Africa Israel USA, said of Leviev and Pa. “And so they did. There was a good relationship.”

But when the financial crisis hit, Leviev’s global conglomerate was brought to its knees. Desperate for funds, Leviev put his New York real estate holdings on the market. Pa stepped forth as an eager buyer.

In August 2008, China Sonangol signed a memorandum of understanding to pay $150 million for 23 Wall, another $150 million for a 49.9 percent stake in the Clock Tower at 5 Madison Avenue and $50 million for a 49 percent stake in the former New York Times building at 229 West 43rd Street, according to a report by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. The deals for Clock Tower and the Times building never closed, but the 23 Wall deal went through in November 2008, property records show.

“A New York developer probably wouldn’t have paid $150 million for it,” Marin, who joined Africa Israel after the deal, said, chuckling. (Marin was fired by Africa Israel in December 2010 and later sued the firm). “For a foreigner that has a lot of cash flooding its coffers every day, it probably didn’t sound like the stupidest thing in the world,” he noted. “It wasn’t like buying swampland in New Jersey, you know.”

Why would Pa overpay for a Wall Street property two months after Lehman Brothers went under? According to one theory put forward by several sources, China Sonangol was raking in so much money from its Angolan oil fields that any half-decent investment to put those profits to use would do.

“They were just stashing money,” a source said.

But maybe China Sonangol didn’t understand what it was buying. According to Marin, the firm’s executives visited the property for the first time about a year after the purchase. Ted Bulow, a middleman between Chinese and American investors who later talked to China Sonangol about a potential sale of the building, made an even more remarkable claim: An employee of the firm told him the bosses thought they were buying the 50-story Clock Tower, not the four-story 23 Wall. Jona Rechnitz, who served as Africa Israel USA’s head of acquisitions and dispositions at the time of the sale, told the New York Post the same thing. Rechnitz did not respond to several requests for comment.

When viewed in isolation, the 23 Wall deal seems bizarre. But it was just one of many transactions between Leviev and Pa.

A week before China Sonangol signed a memorandum of understanding to buy the Wall Street property, Leviev and two of his companies bought a minority stake in a natural resources company controlled by Pa’s group, according to the commission’s report. And Pa’s group bought Leviev’s stake in the Catoca mine in Angola for $400 million in 2011.

By that time, Pa had gotten to know the brutal regime of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe. Mugabe had ruled the Southern African country since its independence from white minority rule in 1980, but in the late 2000s his grip on power had started to weaken. In February 2009, his party was forced to invite the opposition into a coalition government and lost control of the finance ministry. So Mugabe turned to diamonds to fund his secret police, creating a de facto parallel government, according to a report by advocacy group Global Witness.

Pa paid Mugabe’s Central Intelligence Organization a large sum of cash and delivered 200 Nissan pickup trucks, according to the report. Around the same time, a Pa-controlled company landed a stake in the Marange diamond fields in the country’s Manicaland province.

He tapped Leviev for his mining expertise. In early 2011, a mining company controlled by Leviev sampled the Marange fields on behalf of Pa’s group, according to Global Witness. The advocacy group notes it found no evidence Leviev knew about Pa’s support for Mugabe’s secret police.

Selling diamonds from the Marange fields was illegal at the time, following an international ruling aimed at preventing the trade of blood diamonds. According to news reports cited by the Africa Center, Pa solved that dilemma by smuggling tens of thousands of carats out of Zimbabwe in his private jet.

Charles Michael, an attorney representing Leviev, said his client cut ties with Pa once he heard of his “disreputable activities” and “has never had any connection whatsoever with Robert Mugabe’s government in Zimbabwe.” He said Leviev has “no knowledge” of Worldpro Development, disputed that the 23 Wall sale was part of a series of deals and said the claim that China Sonangol didn’t know which building it was buying was “untrue” and “preposterous.”

“The 2008 transaction was between two large companies that had boards, regulators, attorneys, and the like,” Michael wrote in an email, “and it stood on its own.”

An attorney representing China Sonangol did not respond to a request for comment.

For sale by owner

In April 2014, the U.S. Treasury Department put Pa under sanctions for his role in “undermining Zimbabwean democracy.” In October 2015, the Chinese government arrested him amid its anti-corruption drive. Soon after, China Sonangol started looking for a buyer for 23 Wall.

Officially, Pa held no stake in the building or any of the companies under his control and merely served as an “advisor,” allowing them to operate despite the sanctions against him. But he looks to have been directly involved.

“There always had to be surreptitious meetings because he was under house arrest and he wasn’t supposed to be talking to anybody,” said Bulow, who added that Pa’s group approached him about arranging a sale of 23 Wall but never reached a commission agreement.

“That was one of the reasons he couldn’t officially say that he’s selling it,” Bulow said, “because he couldn’t admit that he owned it and that this was hidden in 96 different places.”

The other person seemingly in charge at China Sonangol is a woman named Lo Fong Hung, who — unlike Pa — owns a direct stake in the company. “Everything indicated that [Pa] was the boss,” the former Guinean mining minister Mahmoud Thiam told the FT. “But you got the sense that if he wanted to get rid of Lo, he could not.” In August, Thiam was sentenced to seven years in prison for laundering bribes paid to him by China Sonangol executives.

One New York real estate source, speaking on condition of anonymity, recalled a dinner with China Sonangol’s leadership in a private room behind the restaurant of an upscale hotel. A Chinese woman, whom he perceived to be in charge, kept loudly spitting on the ground throughout the dinner.

“The staff thought nothing of it,” the source said, “because they ran around and cleaned up every time she spit on the floor.”

Year after year, China Sonangol paid over $1.2 million in annual property taxes while 23 Wall sat vacant. In August 2016, it finally seemed to have found a buyer. Jack Terzi, principal of retail-centric real estate investment firm JTRE Holdings, signed a contract to buy the property, which also includes neighboring retail space, for $140 million.

But when Terzi tried to wire over the $17 million down payment, the bank in charge of the escrow account refused to greenlight the transaction, according to a $250 million lawsuit he filed against China Sonangol in December. The reason, the suit alleges, is that the bank needed proof that none of the money would go to Pa, and China Sonangol refused to cooperate.

The deal has yet to close. On a recent Monday, the property’s enormous brass front door was held shut with a flimsy cable lock. U.S. flags hanging off the stock exchange across the street reflected in its pale, cracked windows. Inside, faint neon lighting fell on empty floors.

One source close to the property, speaking on condition of anonymity, said China Sonangol came close to finding a tenant for the retail space several times in recent years, but no deal ever happened.

“I don’t know of a single owner who would do something like this,” the source said. “It’s the kookiest situation ever.”