There is no area of the city immune to the transformative power of retail. Any up-and-coming neighborhood with a new hip coffee shop speaks to that.

There is no area of the city immune to the transformative power of retail. Any up-and-coming neighborhood with a new hip coffee shop speaks to that.

But those retail locations are obviously not selected at random, whether by Starbucks, Duane Reade, SoulCycle or a hot new restaurant. They are painstakingly chosen as part of well thought out real estate growth strategies.

As retail rents keep rising and developers and landlords battle for retailers in both established shopping districts and high-profile future sites like Hudson Yards, The Real Deal looked at the unique strategies of a handful of top retailers from different corners of the market, to see exactly what’s in play when they are deciding where to plant their flags in New York.

What we discovered was a wide variety of approaches, from rapid expansion to selective downsizings. Read on for a look at a cross section of strategies from some of the most interesting players in the market today.

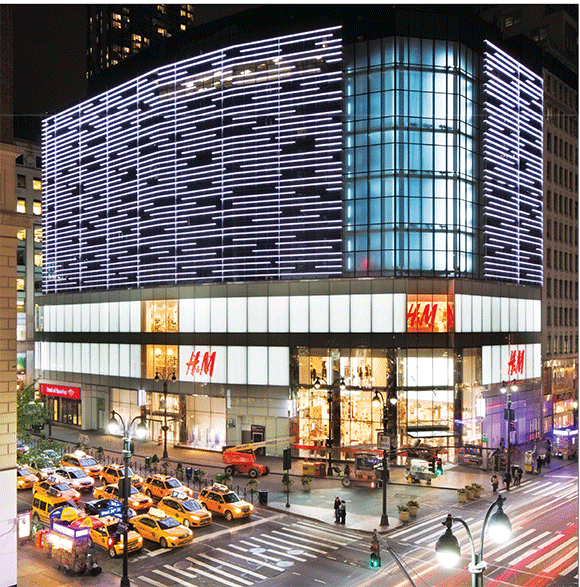

H&M

Fast-fashion juggernaut H&M opened its largest store in the world last month: a 63,000 square-foot flagship at Herald Center.

While the Swedish retailer generally keeps its U.S. stores looking identical, its new flagship includes some unique features, most notably a 35-foot glass façade backed by an LCD display and a 30-foot-high atrium on the second level.

“The simple fact is that we do everything the same,” H&M general counsel Hank Rouda said during a recent forum on retail, explaining that the key to the brand’s success is each location’s “commonality.”

“You will notice the same kind of design, but what we’ve done here in New York — because it’s important to the landlords here in New York — is we said, ‘You know what? We need to make each individual location a little bit unique,’” he said. “We do these little things because we want to create that identity for that location. But the vast majority of our stores, the malls, the middle-America kind of stores, there’s a commonality there, because you can’t be scalable if you don’t have that commonality.”

In addition to helping boost a tenant’s bottom line, a flashy store can also be a boon to landlords, because it can draw attention to their properties and, in turn, raise their profile.

The newest location, owned by downtown-based JEMB Realty, brings H&M’s store count in Manhattan to 12, although the company’s space across the street at 2 Herald Square is now on the market.

Retail expert Robert Gibson, who left Cushman & Wakefield last year to join JLL, has brokered most of H&M’s big deals.

But while casual-clothing competitors like American Apparel, with16 stores, and Gap, with 14 (including GapKids and BabyGap) have more locations in Manhattan, few, if any, have the buzz H&M generates these days when it makes a real estate move.

The retailer usually looks for footprints of 25,000 square feet in prime Manhattan shopping districts such as Soho, Times Square, Fifth Avenue and 34th Street. H&M is also working on rolling out a pair of spin-offs: “&Other Stories,” which focuses on women’s shoes and accessories and which opened a location last year in Soho, and “Collection of Style,” a higher-end brand that is reportedly replacing the first store H&M opened in the city, at the corner of 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue.

Rouda said the company likes to ink its leases a year in advance, though there are exceptions, such as when the retailer locked in a spot at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street about a week after it hit the market.

“We’ve got a couple of deals already approved for 2018,” he said. “So we could definitely do it if it’s a great deal.”

Zara/Inditex

Zara, a subsidiary of the global fashion behemoth Inditex, may not have the most stores among its fast-fashion counterparts. But through its parent company, it does have access to some prime locations.

Zara, which opened its first U.S. store in Manhattan at Lexington Avenue and 59th Street in 1989, has a unique relationship with Inditex, which sometimes buys high-priced real estate for the retailer to open stores in.

The retailer is hailed worldwide as a model of efficient operation through its use of vertical integration: controlling the manufacturing, warehousing, distribution and logistics aspects of its business.

Through its real estate investment arm Ponte Gadea, the Spain-based Inditex owns more than $800 million worth of Manhattan retail property.

Among Ponte Gadea’s prime spots is a retail condo, now leased to Banana Republic, it purchased in 2006 for $107.5 million across the street from Zara’s 59th street location. (Zara remains in the space today, but Inditex does not own it.) It followed the 2006 purchase with the high-profile 2011 acquisition of a $324 million retail condo at 666 Fifth Avenue, and a $94 million retail property in the Meatpacking District in 2013.

And in 2012, Inditex launched another one of its longtime clothing brands in New York, opening a Massimo Dutti on Fifth Avenue in a storefront owned by Vornado Realty Trust.

Inditex — founded by Forbes’ fourth-richest person in the world, billionaire-dozens-of-times-over Amancio Ortega — has not let up on making the real estate the cornerstone of its business strategy.

In January, its real estate arm paid $280 million in an aggressive move to create and buy a 47,000-square-foot retail condo at 503-511 Broadway in Soho, where it will open Zara’s eighth Manhattan location.

Inditex chairman and CEO Pablo Isla called the opening “a significant milestone” for the store’s expansion strategy in the U.S.

“The growth model for the US market consists of a combination of flagship store openings and online sales growth underpinned by strong support from American shoppers,” Isla said in a statement earlier this year, “and this acquisition dovetails perfectly with this strategy.”

Ripco Real Estate’s Jeff Paisner, who represents Zara, explained that the acquisitions also make sense as a pure real-estate play for Inditex. “They’re cash rich, and they just want to have some cash in America,” he said.

Industry pros suspect that the propensity to buy real estate and the coordination with the clothing brands come from Ortega himself.

“That’s the mothership making the decision,” one commercial real estate executive said.

Apple

Ubiquitous” is an understatement when it comes to the way Apple’s products have infiltrated everyday life, so it may come as a surprise that the company still has not conquered a number of major retail frontiers in the city.

More than a decade after opening its first New York store at the corner of Prince and Greene streets in Soho in 2002, the company is just now planning new stores in Queens and Brooklyn.

“I think the boroughs have always been chasing them,” said Faith Hope Consolo, chair of Douglas Elliman’s retail group. “I think Brooklyn was a natural move; it was just a matter of the right space and the right time.”

Apple opened its first outer-borough store at the Staten Island Mall in 2005. Now, as the company looks to expand its footprint (especially in China) it has plans to open stores on Bedford Avenue in Williamsburg and the Queens Center Mall in Elmhurst.

Those two, along with another planned location at the World Trade Center, would bring the tech company’s store count in the city to 10, up from four in 2009.

“This is actually a typical luxury-expansion strategy,” into secondary markets, said Consolo, who added that the company’s 2011 redesign of its flagship Fifth Avenue store was modeled after a flagship store in Shanghai.

In her 2014 book, “The Liar’s Ball,” author Vicky Ward detailed some of the surprised reactions to how well the store at the base of the GM Building did in such an unconventional space.

Fried Frank attorney Rob Sorin, upon visiting the store for the first time, lamented he hadn’t negotiated a larger percentage rent from Apple for his client, then-building owner Harry Macklowe.

“‘Apple really had no idea what this store was going to do in business per year, and we negotiated the ‘stop’ at a level that turned out to be horrendously low,’” he told Ward. “‘The first year, they made $1 million a day.’”

Boston Properties CEO Mort Zuckerman, who bought the building from Macklowe, is quoted in the book saying that the store gives him a special sense of pride.

“‘Whenever I want to cheer myself up, I just take a walk around the Apple Store,’ he said. ‘They make $665 million a year for 10,000 square feet — in a windowless basement.’ He smiled. “Think about that.’”

Apple uses a single broker across the country, Texas’ Open Realty, which works exclusively in Manhattan with Robert Futterman’s brokerage RKF and in Brooklyn with Chris DeCrosta and Hank O’Donnell of Crown Retail Services. DeCrosta did not respond to requests for comment.

MetroPCS/T-Mobile

The wireless providers MetroPCS and its parent company, T-Mobile, are not only among the city’s largest chain retailers, but they are also the fastest growing.

Separately, the two brands ranked in the city’s top 10 retailers last year with a combined 471 locations, according to the Center for an Urban Future’s 2014 edition of its annual report ranking chain retailers by number of locations. A little more than 60 percent of those locations belonged to the prepaid provider MetroPCS.

The two companies each grew their store counts by more than 13 percent from the prior year, adding a net of 56 combined New York City locations from 2013 to 2014.

Its real estate expansion strategy has been in the making for a while.

Back in 2007 when it was trying to catch up with competitors, T-Mobile launched a retail-growth initiative that allowed outside companies to run its branded stores. (It’s not quite a franchise, as T-Mobile doesn’t collect franchising fees.)

And while T-Mobile is still far behind industry leaders Verizon Wireless and AT&T Mobile in terms of customers, it is adding customers at the fastest pace in the industry, closing in over the past few years on Sprint, the No. 3 provider.

The stores are scattered across the city in almost every kind of retail space imaginable, with T-Mobile preferring footprints in the range of 1,000 to 2,400 square feet and MetroPCS usually taking 1,000 square feet or smaller.

“Our competitors had a stronger foothold in branded distribution,” Michael Sentowski, vice president of T-Mobile’s national dealer programs, told the blog WirelessWeek in 2012. “We felt the best way to get there was with third-party partners.”

T-Mobile declined to discuss its strategy for this story, but the company is also inking big deals that raise its profile.

In April, TRD reported that T-Mobile signed a lease for $8 million a year, or about $2,000 per square foot, to lease roughly 4,000 square feet at Vornado’s 1535 Broadway in Times Square. In addition, the retailer is on the hook for another $5 million to lease LED signage above the store.

JLL’s Paul Berkman represented the cell-phone provider in the deal.

Coach

Not all retailers have a voracious appetite for space. Since the handbags and accessories company hired designer Stuart Vevers as creative director last year to revitalize its brand, Coach has embarked on a plan to reduce its footprint in North America by about 20 percent, and to focus instead on reinvesting in and upgrading its prime locations.

The recently revamped interior of the Coach flagship at Time Warner Center

Between 2000, when the company went public, and 2008, Coach grew to more than 350 stores plus nearly 200 outlets, including 10 in Manhattan. But as sales slumped, company executives determined the expansion diluted the designer’s luxury brand.

Coach started closing stores last year, including its uptown stores at 85th Street and Madison Avenue and 84th Street and Broadway. The remaining locations, including its Flatiron store at 79 Fifth Avenue and 595 Madison Avenue in the East 50s, will get remodels, with features like industrial-chic finishes, LED screens and iPad-wielding sales associates — all intended to reflect the new strategy, which aims to heighten the brand’s cache.

The jewel in the Coach crown is its flagship store at the Time Warner Center, where it debuted its new look just in time for the 2014 holiday season. And the company is planning to open another high-profile location at Hudson Yards.

Left to right: JLL’s Robert Gibson; Ripco’s Jeffrey Paisner; CBRE’s Richard Hodos; Newmark’s Jeffrey Roseman

CBRE vice president Richard Hodos, who represents Coach, said the company is not unique in its strategy to contract and upgrade. He said retailers are increasingly using their stores as “showrooms,” that allow consumers to peruse items they later purchase online.

“Retailers aren’t talking about adding stores,” he said. “In most cases, they’re talking about closing stores, getting rid of the lower stores in ‘B’ and ‘C’ malls and investing in ‘A’ street stores.”

“That’s good for New York, because where do people want to put their bigger flagships? They want to put them in New York, Chicago, L.A.,” he said. “For the most part retailers want to focus there.”

Starbucks

After opening its first New York City store on the Upper West Side more than 20 years ago, Starbucks now boasts the largest footprint of any chain in Manhattan. But last year, the retailer that has marked the gentrification of many New York neighborhoods was closing and relocating a number of its older stores.

Now, like many retailers, it is using New York City to test out some new concepts.

With the help of broker David Firestein of the Shopping Centers Group, Starbucks expanded from its first store at 87th Street and Broadway to nearly 300 locations across the five boroughs last year.

While the Seattle-based company has just a little more than half the number of stores across the five boroughs of its New England-based competitor Dunkin’ Donuts, Starbucks does have the edge in Manhattan with 205 stores, according to the Center for an Urban Future’s survey.

But that number was down by seven from the previous year, and sources said that as Starbucks leases inked during its expansion years expire, the company is reassessing its locations.

That includes the high-profile store at the corner of 17th Street and Union Square West, where the asking rent has more than doubled to $650 per square foot since the coffee house signed its lease 15 years ago.

The buzz term now at corporate headquarters is “disciplined expansion” — the discipline, that is, to be more selective in choosing locations to open in, instead of being hell-bent on saturating a market.

Part of the strategy is testing out concepts such as 500-square-foot express stores with limited menus and, on the other end of the spectrum, a high-end-style café that will mimic the feel of an independent coffee shop.

Because the Starbucks brand is so established, observers said, customers are willing to go the few extra steps for their cup of Joe, so Starbucks doesn’t necessarily need to be on every prime corner.

“I think that they took these great corners years ago as they were expanding and now that their customers are addicted feel they can go off the corner,” said Jeffrey Roseman of Newmark Grubb Knight Frank, who is marketing Starbucks’ space on Union Square West. “They feel they don’t have to be on Main and Main anymore.”