One Manhattan West will eventually become a glitzy office tower, but for now it’s a mammoth fort looming over Ninth Avenue — a thick concrete core, surrounded by a cage of metal. The large banners draped over the top of the building declare its conquerors or, rather, its construction team: Tishman Construction and Navillus Contracting.

One of those names not only adorns the uppermost reaches of the unfinished spire, it also tops The Real Deal’s first-ever ranking of the city’s top 20 general contractors for new construction — the muscle behind New York City development.

Over the last five years, the company now officially known as AECOM Tishman logged 13.8 million square feet of work approved by the city’s Department of Buildings. That’s not only more than six Empire State Buildings’ worth of space, it is also 77 percent above the total for runner-up Turner Construction.

“We like diversification,” said Jay Badame, AECOM Tishman’s eastern regional president.

The company also fared well in TRD’s ranking of the top 20 firms doing alteration and renovation work, based on the value of their projects in the city. There, AECOM stood fifth, with $799 million worth of projects in the period, though far behind Manhattan-based Structure Tone’s list-leading total of $2.6 billion.

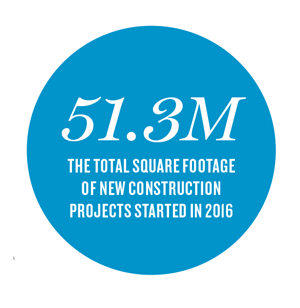

Taken together, the two new rankings of contractors show the remarkable scale of their success over the last five years. While the volume of new construction tumbled 38 percent last year from the lofty levels of 2005 — to 51.3 million square feet, according to the New York Building Congress — that sum still stands nearly 16 percent above the average for the previous five years. And while the luxury condo market has waned in recent months, major projects such as the redevelopment of LaGuardia Airport and East Side Access, which will bring the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central, have proceeded apace.

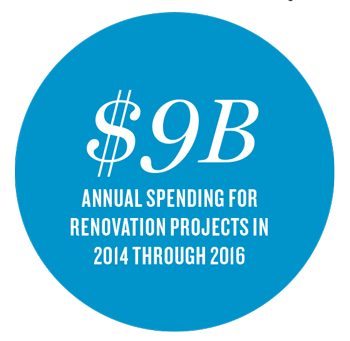

Meanwhile, demand for alterations and renovations has taken off. A recent Building Congress report praised such work as the “unsung hero of the current building boom,” and pointed to data showing that total annual spending for such projects in 2014 through 2016 soared to an average of $9 billion. That represented a major leap from the average annual spending of $5.5 billion between 2011 and 2013.

“While all eyes are understandably focused on the brand-new office and residential towers that are piercing the New York City skyline, an extraordinary amount of important construction work is occurring, largely under the radar, throughout the five boroughs,” the trade group’s president, Carlo Scissura, stated in the report.

But despite those figures, the industry faces profound challenges this year as it enters an unaccustomed period of rising interest rates, an unusually cloudy economic outlook and uncertainty over the fate of President Donald Trump’s proposed $1 trillion in infrastructure projects. To better position themselves, several construction companies have acquired subcontractors and even edged into development work themselves.

Meanwhile, not to be outflanked, several developers have moved in the other direction by taking over their own construction work. In both cases, the desire to control costs looms large, as it does in the increasing use of nonunion labor — a practice that has spread to even some of the largest and most complex building projects. What’s more, to hedge their traditional work with private developers, many contractors are ramping up efforts to land big public-sector projects as well as in affordable housing.

“Right now, the market is hot, but there are a lot of condos coming online,” said Donal O’Sullivan, president of Navillus, which works as both a general contractor and a subcontractor that specializes in concrete and tile. While Navillus has worked on major NYC projects, including the renovation of Grand Central Station, the company did not rack up enough work in the five-year time frame to make either ranking.

“We’re looking at infrastructure now because that’s where the money’s going to be,” O’Sullivan noted.

Building a bigger tent

When it comes to contractors bulking up through acquisitions, AECOM is the reigning champ. In the last few years, the Los Angeles-based company has added hugely to its construction business. Most notably, that included the July 2010 purchase of Tishman Construction, which has done general-contracting and construction-management work over the last five years in the city for projects that include the 2.8 million-square-foot 3 World Trade Center and the 1.6 million-square-foot One Vanderbilt. (The former project is not included in this ranking since it does not appear in DOB records.)

Four years after purchasing Tishman, AECOM scooped up Hunt Construction, which specializes in sports arenas, having worked on Citi Field in Flushing, Queens, and the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta. At the same time, the multinational engineering firm has expanded its tool kit. Badame noted that the company’s construction division is poised to bid on projects involving newer project delivery methods, such as design-build. Last month, AECOM broke ground on another front, announcing the creation of a division to focus on contracts with the federal government. That growth has paid dividends for both the parent firm and its subsidiaries.

AECOM CEO Michael Burke led the most ground-up construction in New York City in the past five years.

“When we joined AECOM, our geographic footprint expanded from two countries to over 25,” said Badame. “At the same time, construction has become a much more significant part of AECOM’s overall business.”

Other companies are acquiring subcontractors like electrical, mechanical and concrete companies, among others, to help expand their reach. Sydney, Australia-based construction firm Lendlease recently acquired an engineering firm.

“These acquisitions give [companies] a greater ability to control [their] destiny,” said Ralph Esposito, who oversees Lendlease’s construction projects on the East Coast. “The companies that have their own plumbing company, for instance, have the advantage because they have greater control over their costs.”

In search of even bigger gains, Lendlease, which ranks third on TRD’s new-building list with 18 projects totaling 7.7 million square feet, took an even bolder step two years ago. It leaped into the development game in New York by purchasing an unspecified stake in 281 Fifth Avenue, a 200,000-square-foot condo tower it’s co-developing with the Victor Group.

“For the first time in a long time, several of the larger general contracting companies have decided that there’s a value and ability to [develop themselves],” Esposito said.

That move comes as a handful of developers, including JDS Development Group and DDG Partners, have tacked in the opposite direction, taking on their own construction work. In doing so, they follow in the steps of Related Companies, whose own construction arm has served as general contractor on some of the company’s highest-profile projects — including the first Hudson Yards tower to be completed, 10 Hudson Yards, and the Zaha Hadid-designed condo building on the High Line, three blocks south.

That move comes as a handful of developers, including JDS Development Group and DDG Partners, have tacked in the opposite direction, taking on their own construction work. In doing so, they follow in the steps of Related Companies, whose own construction arm has served as general contractor on some of the company’s highest-profile projects — including the first Hudson Yards tower to be completed, 10 Hudson Yards, and the Zaha Hadid-designed condo building on the High Line, three blocks south.

Jeff Schotz, executive vice president of leasing and marketing at New York-based SJP Properties, said that strategy has paid off handsomely for his development firm for more than three decades. A case in point is Prudential Financial’s new headquarters in Newark, which SJP is building. Schotz noted that not every developer is equipped to take on its own construction work, but doing so allows greater control over a project’s schedule and costs. “It means we’re not beholden to any subcontractors,” he said. “We’re not beholden to any third parties.”

The relationship between developers and general contractors, by design, is an adversarial one. General contractors — which are often interchangeable with construction managers — often bid on projects as “lump sum” contracts, meaning that they can keep anything that they don’t spend on subcontractors. Among other things, that gives them an incentive to cut costs. In instances where the owner and contractor disagree on charges, the former often sides with the subcontractors, since it has no reason not to.

“It’s a better alignment of incentives to have the owner and management be the same,” JDS’s CEO Michael Stern said. “We can control the process better.”

Be that as it may, the far shorter track record of most developer-owned construction firms could raise caution flags among potential lenders down the road, especially in dicier market conditions. Badame notes lenders prefer that developers select general contractors who have worked extensively on projects similar to whatever they are currently building.

“Many of the developers doing this haven’t seen the downside of the economy yet,” he said.

Opting for the interior

As is frequently the case, contractors doing building renovations today operate on a somewhat surer footing than those putting up residential and office buildings from scratch. Many landlords are racing to revamp their properties to compete with new office space springing up in Hudson Yards, Lower Manhattan and elsewhere. What’s more, the likely rezoning of Midtown East could add over 6 million square feet of new office space in the next 20 years.

Jim Donaghy, executive chairman of Structure Tone, noted that some of the city’s biggest landlords — SL Green, Vornado Realty Trust and Tishman Speyer, to name a few — are updating their existing building stock to keep up with tenants who are increasingly demanding high ceilings, expansive lobbies, modern elevators and other amenities provided in newer properties.

“Tenants are all fighting over the newer buildings,” he said. “It’s putting a lot of pressure on these old buildings to keep up with these new designs.”

One of the overall takeaways is that it’s a good time for contractors helping landlords reposition their properties. Curiously, while many of the top 20 firms doing renovation work are units of larger construction groups such as Skanska and Turner Construction, the No. 1 player ranked by initial cost estimates filed with the DOB is a private company that largely focuses on interior work. The construction management and general contracting services firm Structure Tone averages 700 projects a year in the city. Among the largest of them was engineering MetLife’s 430,000-square-foot expansion at 200 Park Avenue in 2015.

While Structure Tone often sticks with its niche, that doesn’t mean management feels it can just stand still in the marketplace. Instead, Donaghy’s family, which has run the company since 1971, decided in January to open control up to 75 company managers and some outside investors as part of its efforts to shift to an all-employee ownership structure. In doing so, it rejected other options — including selling the company or taking it public.

“The need to produce a bottom-line return to shareholders who don’t even work at the company, that to me alone is a real disrupter to the culture of our company,” Donaghy said. “We don’t want to move to the ebbs and flows of the market.” Instead, Structure Tone now seeks to grow through mergers with companies on the West Coast and in Canada and Europe, he noted.

Legislative aid

Spurred by President Trump’s proposed $1 trillion in infrastructure spending, some construction firms are eyeing potential work in that market. But it’s not as easy for some of the smaller firms that specialize in residential and office buildings to jump in as it is for the large companies that have divisions that specialize in that kind of work.

“The condo market is still strong but certainly not strengthening,” Lendlease’s Esposito said. “It’s about being a smart, diverse business that doesn’t have its eggs in one basket.”

Turner Construction is the muscle behind the renovation of Rockefeller University on the Upper East Side.

Closer to home, the state’s newly revived 421a residential tax break, now known as Affordable New York, is expected to provide a much-needed jolt to apartment construction in the city. Residential construction starts dropped to $11.5 billion from $19.5 billion the previous year, a decrease the New York Building Congress primarily attributed to the tax exemption’s absence. Tellingly, just days after the governor signed off on the measure, the Durst Organization told the TimesLedger newspapers that it will move forward with its stalled $1.5 billion Hallets Point project in Astoria, which is expected to include 2,400 residential units, of which 484 will be affordable.

That renewed tax break comes at a cost, however. To qualify for the break, contractors will have to pay average wages of $60 an hour on certain Manhattan projects and $45 an hour in parts of Brooklyn and Queens. That condition comes after decades of efforts by contractors to rein in their labor costs by using nonunion labor. On the other hand, supporters of union construction argue that it’s inherently safer, given the training required for its members and its long history in the city.

“The union contractors have been around for 100 years, so there is stability there, which we like,” Badame said, noting that Tishman hires union subcontractors.

After years of rapid growth, however, nonunion projects account for as much as 50 percent of the overall market, spurred by cost savings that range from 15 to 30 percent. Many of the general contractors who spoke to TRD indicated that they are moving toward an open shop model to control their costs — meaning that they hire both union and nonunion companies.

After years of rapid growth, however, nonunion projects account for as much as 50 percent of the overall market, spurred by cost savings that range from 15 to 30 percent. Many of the general contractors who spoke to TRD indicated that they are moving toward an open shop model to control their costs — meaning that they hire both union and nonunion companies.

William Gilbane III, senior vice president of Gilbane Building Company, said his firm prefers to call it the “merit shop” model, emphasizing that his firm wants the best subcontractors for the job “regardless of union affiliations.” Gilbane ranked fourth on the new-building ranking with 7.6 million square feet of construction. Gilbane has lots of company in embracing the “merit shop” label.

“Open shop to me sounds like a free-for-all,” Donaghy said. “Merit says what’s best for the client is awarding to the best companies.”