For the last several months, economists, lobbyists, advocates, talking heads, editorial boards and everyone else with a pulse who runs in Washington circles has been talking about the prospect of tax reform.

For the last several months, economists, lobbyists, advocates, talking heads, editorial boards and everyone else with a pulse who runs in Washington circles has been talking about the prospect of tax reform.

But as the industry rings in 2018, that reform, the first major overhaul to the U.S. tax code in 30 years, is now reality.

With the ink barely dry on Donald Trump’s signature, the industry is now scrambling to digest the president’s first legislative victory since moving into the White House — not to mention the now-famed 11th-hour additions that were scribbled into the margins of the document. And, as The Real Deal has been reporting, the results for the industry are decidedly mixed.

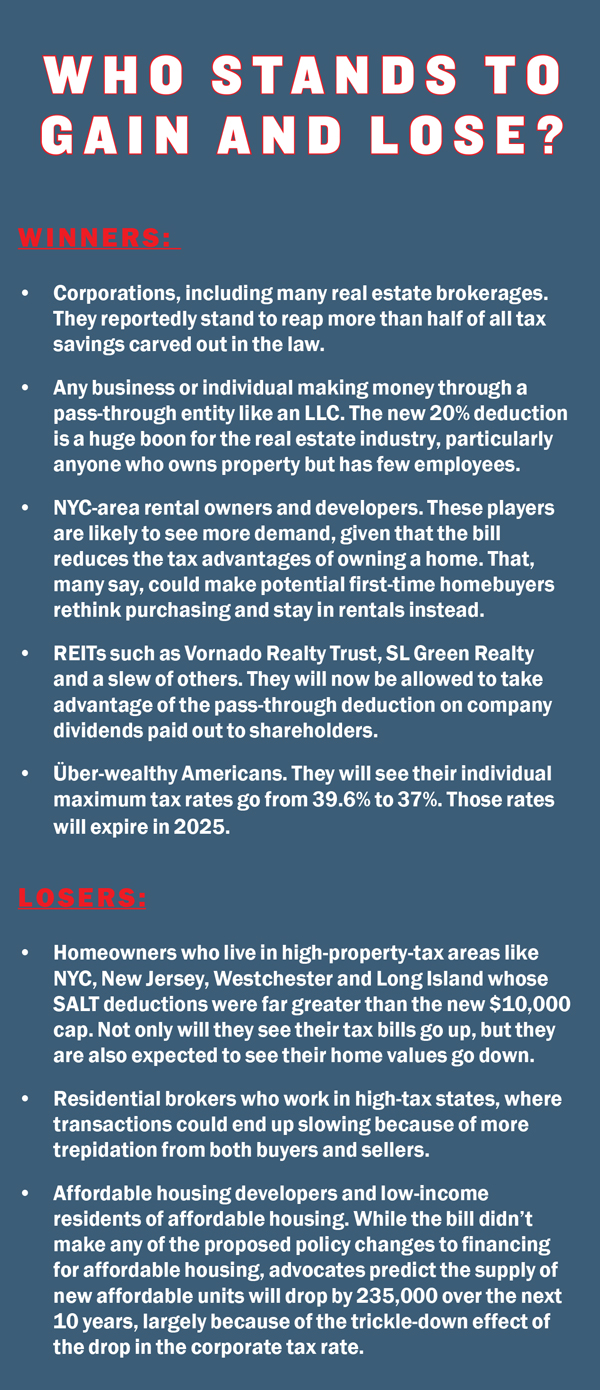

While the commercial side is rejoicing at the deep cuts that the GOP doled out for corporations and so-called pass-through entities, the residential sector, particularly in the suburban ring around the city, is bracing for hikes and for a trickle-down effect that economists say could hurt not just the residential market, but also local economies. The bill, it should be noted, also carved out new benefits for real estate investment trusts and will be a boon for the über-wealthy.

“Everything that I’m seeing is extremely positive to commercial real estate,” said Marcus and Millichap’s John Krueger, a commercial sales broker who recently sold a $73 million Brooklyn portfolio.

But Krueger, who lives in Westchester, acknowledged that he might personally see tax increases because the new bill caps the amount of state and local taxes, otherwise known as SALT, that homeowners can deduct from their federal tax bill.

“It’s definitely going to be a challenge,” he said.

Still, he opted for a positive spin on that challenge, noting that “at the same time [it will] spur on more opportunities to earn more.”

“Then you just have to pay more taxes,” Krueger said. “You would hope it would offset. I don’t know. To be determined.”

Others were less optimistic.

The National Association of Realtors — the industry’s largest lobbyist — and many other analysts have said that measures such as doubling the standard deduction to $24,000 for married filers basically kills the effectiveness of the mortgage-interest deduction. That’s largely because it prevents the use of itemized deductions for many filers.

Disqualifying homeowners from using it, along with the reductions in deductible property taxes, they argue, could lead to a drop in residential transactions. In a nutshell, it reduces the tax benefit of owning a home for many in the New York area.

In addition, affordable housing advocates are unnerved about how the new corporate tax cuts will eat into the pipeline of new supply.

Manhattan Rep. Carolyn Maloney, a Democrat, said she was “extremely upset about this tax bill.”

“It’s like a war against New York City,” she told TRD shortly before the agreement was signed last month. “The loss of deductibility hurts New York and other states that contribute the most to the economy and the U.S. Treasury.”

And, she said: “It’s a whammy to affordable housing.”

Commercial sector bonanza

The way some real estate players have been talking about it, it’s hard to imagine how the commercial industry could possibly have survived without tax reform.

“This is the only chance we have to spur the economy,” billionaire Douglas Elliman Chairman Howard Lorber, a Trump buddy, told CNBC in May when the reform was just being bandied about.

That same month, developer Don Peebles said it would benefit New York real estate companies and “stimulate far greater development.”

“He can be transformational for real estate,” Peebles said of Trump.

That transformation is now underway for the industry.

In the days before the tax reform bill actually passed, real estate lobbyists were feverishly scrambling to get last-minute changes into the final version. For many, it was a flashback to 1986 — the last time a major tax reform with serious real estate consequences passed.

In the sleep-deprived days at the end of 2017, lobbyists were trying to fix what they deemed a problem with the Senate version: Not enough real estate companies would qualify for a 20 percent deduction of qualified business income for pass-through companies — or businesses structured as LLCs, S corporations and certain kinds of limited partnerships.

As one lobbyist explained, lawmakers were looking for a way to allow real estate firms and other businesses that have small payrolls to get in on the pass-through tax cut bonanza.

And in the end, the real estate lobby got what it wanted.

The bill created a new 20 percent deduction for all pass-through companies, but caps those deductions based on payrolls. However, lobbyists succeeded in getting an extra cut for firms with small headcounts. Those entities can deduct 2.5 percent of the purchase prices of all their depreciable property — or nearly all of the property they own — on their annual tax bills. (Additionally, the rate at which owners can depreciate the value of buildings for tax purposes has been accelerated — a measure that will further lower tax bills.)

That means firms with small staffs —from the Extell Developments to the family-owned firms in the outer boroughs — stand to save millions of dollars a year.

“A lot of the bigger shops have their own internal construction department,” said Christine McGuinness, head of the real estate practice at law firm Schiff Hardin. “But there are many, many developers out there that sub it out, so I do see that as a big incentive.”

But that’s just one benefit.

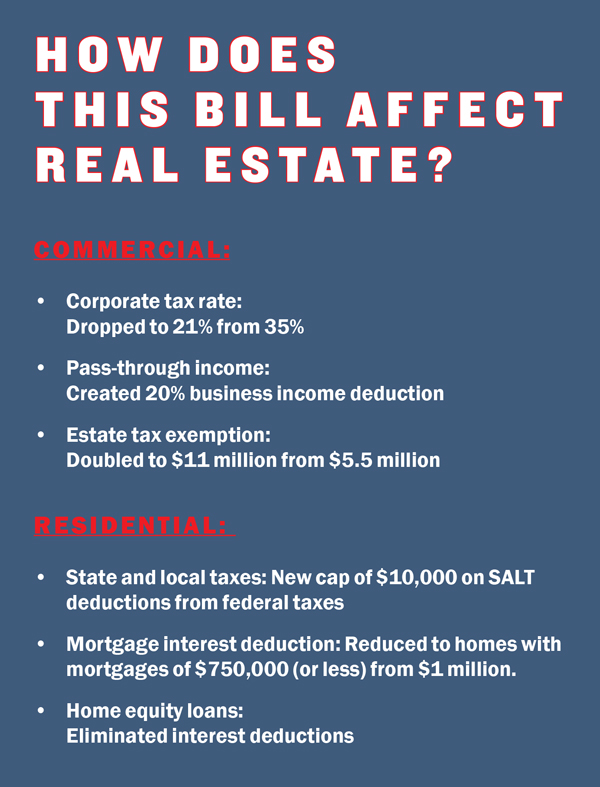

The top corporate tax rate will see a giant drop, sinking to 21 percent from 35 percent, so real estate companies structured as corporations are set for major cuts.

Meanwhile, REITs — like Vornado Realty Trust, SL Green Realty, Boston Properties and a slew of others — got their special handouts, too. The bill allows those companies to take advantage of the pass-through deduction on company dividends paid out to shareholders.

Richard Anderson, a REIT analyst at Mizuho Securities USA, said effective tax rates for REIT shareholders will go to 29.6 percent from 39.6 percent because of the new rules.

“That’s a 30 percent deduction of taxation of your REIT dividends, which is good,” he said.

Sandy Davis, a tax attorney at the law firm Akerman, said “REIT interest holders fare quite nicely.”

Before the bill was finalized, commercial real estate executives were worried that 1031 exchanges — a pet industry incentive that allows investors to defer paying taxes on capital gains from building sales when they reinvest the proceeds in a new building — would be eliminated. But in the end, 1031s were left untouched.

“There had been some thought or fear that the benefit might be cut back,” Davis said. “It was cut back for exchanges involving business equipment and assets … but the provision for real estate was kept intact.”

Trump and Congressional Republicans also didn’t touch the carried interest loophole — which allows certain investors, like private equity firms, hedge funds and some real estate players, to treat profits like capital gains and pay less tax. Trump derided that loophole during the campaign, saying hedge funders were “getting away with murder.”

In the end, Trump’s economic adviser Gary Cohn blamed the lobbyists. “The reality of this town is that constituency [hedge funds and private equity] has a very large presence in the House and the Senate,” Cohn told CNBC.

Residential ruin?

If the mood is upbeat in the NYC commercial world, it’s undoubtedly more somber among single-family homeowners and the brokers who work in that space.

The new tax code targets three key provisions that make owning a home financially attractive: It limits the mortgage-interest deduction to loans of $750,000 (down from $1 million); it creates a $10,000 cap on SALT deductions; and it eliminates interest deductions for home-equity loans, which owners tap when they do home renovations.

The changes are expected to hurt residential values in high-property-taxes states like New York, New Jersey and California — which, as many have pointed out, all voted Democratic in the presidential election.

An analysis from Moody’s Analytics predicted that housing prices could fall by 10.4 percent in Manhattan (compared to where they would have been without the tax bill), and even more in some of the surrounding areas. Of the 20 counties it predicted will see the steepest declines relative to projected growth, 17 are in New York or New Jersey.

That’s because taxes and median home prices are well above the national average, so they will be most impacted by the new SALT cap deduction.

And the bill, some experts predicted, will put indirect economic pressure on local economies. If residents have to pay higher taxes, they have less money to spend.

“If you hurt jobs, you hurt incomes; if you hurt incomes, you hurt housing prices,” said Moody’s chief economist Mark Zandi, the report’s author.

Zandi attacked the premise that the growth spurred by the bill will pay for itself, which Republicans have argued. Given that the economy is at full employment, he argued, a stimulus bill won’t work.

“It’s a very costly way to go nowhere,” he said. “It’s creative in a Machiavellian way.”

Brokers had varying takes on how much the residential market would suffer but noted that some sectors would take the brunt more than others.

“You’re going to see a lot of first-time homebuyers sitting on the sidelines,” said Mark Chin, head of Keller Williams’ Tribeca office. “For sure for the next 12 months.”

Nevertheless, given that supply is short in the under-$2 million Manhattan market, Chin said he doesn’t expect the bill to slow transactions much.

Compass President Leonard Steinberg, who publicly expressed his concerns with the bill on social media, agreed that the lower-end Manhattan market will remain strong and said he doesn’t see the high-end luxury market feeling the effects of the bill much. But he said the middle of the market could take a hit.

Ideal Properties Group founder Aleksandra Scepanovic said she recently had a couple back out of a contract on a Brooklyn property, which was priced between $2 million and $3 million, because they were unsure how the final bill would affect them. “What we have been seeing, following the initial draft of tax overhaul bill, is significantly more trepidation on the part of homebuyers in Brooklyn, especially,” she said.

In addition, as the Wall Street Journal recently reported, all of this might put a squeeze on jumbo mortgage lending, which is huge in New York.

The situation is most troubling in the area’s suburbs.

Chris Meyers, president of residential brokerage Houlihan Lawrence — which modeled out what the new measures would mean in Westchester, Fairfield and Dutchess counties — said the bill could have a big impact on those considering buying.

“We are seeing a net reduction of purchasing power to a homebuyer of 10 and 15 percent,” Meyers said. That, however, could be offset by other changes in the bill that increase after-tax income, he said.

As for transaction volume, it could hurt the higher end, he said, but was unlikely to affect starter homes, where inventory is already short. If anything, a drop in supply could put upward pressure on prices, he said.

While speculation about the sales market swirls, most agree that the rental market will benefit.

“Rental landlords are laughing all the way to the bank,” said Keller Williams’ Chin. Not only are these reforms very likely to increase demand for rentals as buyers rethink whether to pull the trigger on sales, but the bill itself has goodies for rental landlords. That, Chin said, could spur investors to put money into the rental sphere.

“When investors see how tax-advantaged being a rental landlord is, you’re going to see increased international investment in multifamily,” he said.

Dan Aviles, a multifamily investment broker in Marcus & Millichap’s New Jersey office, said luxury rentals especially stand to gain as demand jumps from those who might have otherwise bought a first home.

Seth Pinsky, an RXR Realty executive who focuses on commuter markets, agreed, noting that the bill altered the calculus between renting and buying.

Nevertheless, Pinsky said his main concern is what the bill will do to the city’s economy.

“This is a dramatically new reality that New York City is going to be operating [under],” Pinsky said. “In many ways this tax bill was deliberately and maliciously designed to hurt this region.”

Affordable hurting

While affordable housing policy was technically not targeted in the final tax reform bill, the space is bracing for a major scale back.

But things could have been even worse.

When the House of Representatives passed its initial version of the bill, it was mayday for the sector.

The effect of proposed slashes to Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC)— the federal tax incentives used to spur the development of affordable housing — combined with a proposal to eliminate the tax-free status of private activity bonds sent shock waves through the advocacy community. If implemented, the reforms were expected to lead to a $4.5 billion drop in affordable housing investment annually, which, according to the advocacy group the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), would have led to 800,000 fewer affordable units built over the next decade.

Developers in the New York area who work on affordable housing said the hit to private activity bonds would have had an instant impact.

“We would absolutely have to completely go back to the drawing table,” said Greystone’s Chris Eisenzimmer, a director in the firm’s affordable housing practice, which partners with nonprofits to preserve affordable housing.

“The assets would no longer be able to be preserved,” he said.

For example, the restoration of an 842-unit affordable building the company just financed in Newark using so-called 4 percent tax credits — only available for projects that get the majority of their funding from private activity bonds — would have had a very hard time competing for other funding sources, he said.

So the industry breathed a huge sigh of relief when private activity bonds were ultimately spared the chopping block. But while the bill didn’t make any direct changes to affordable housing policy, sources said it will still have devastating effects. That devastation, sources argued, stems largely from drops to the corporate tax rate and from the deficits the bill is expected to create.

Diane Yentel, the president of NLIHC, argued that those deficits — which are pegged at more than $1 trillion — could “trigger automatic funding cuts to the national Housing Trust Fund,” the government fund that allocated about $175 million in 2016 to projects reserved for extremely low-income Americans.

“By increasing the deficit so significantly, I certainly expect to see an aggressive attempted push to cut spending for affordable housing and community development programs, and really across the entire social safety net,” Yentel told TRD.

An analysis by the Manhattan-based accounting firm Novogradac & Company predicted that dropping the corporate tax rate to 21 percent would reduce the supply of new affordable homes nationally by 235,000 over the next 10 years. That’s mostly because the price of LIHTC will drop as fewer corporations buy the credits, because they have less tax liability to offset now.

According to estimates from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, LIHTC financed more than 100,000 units in New York State, mostly in New York City, between 2005 and 2014.

While HUD was not directly impacted by this bill, the Trump administration announced in the spring that it wants to cut the agency’s budget by billions, including cuts that would affect New York public housing and programs that help lower-income New Yorkers buy homes.

On a more macroeconomic level, affordable housing experts are concerned that if home values drop as a result of the bill, rents will rise and the need for affordable housing will actually grow, said Karen Haycox, CEO of Habitats for Humanity NYC. But, she said, the biggest concern is the unknown.

“I don’t think anyone knows the full impact of this bill, even the Republican senators who voted for it,” she said.

To incorporate or pass through?

Most large companies can’t go wrong with this tax bill and can expect to see more of their money stay in their own hands.

But the bill has set many companies and agents scrambling to determine whether they should restructure, or even can restructure, to reap the greatest financial benefits.

The two main options — pass-through entities and corporations — come with different upsides.

The final bill allows many brokers working as independent contractors or through pass-throughs to take the 20 percent deduction, but only if they make less than $157,500 as a single filer or $315,000 if filing with a spouse.

“I do think that will maybe be the next thing you see from this: How do we become a pass-through?” Schiff Hardin’s McGuinness said.

But corporations are seeing an enormous drop in the tax rate, going to 21 percent from 35 percent.

Many brokerages — Realogy and Keller Williams, to name a few — are structured as corporations and are likely to stay as such.

Figuring out how to proceed is already keeping tax attorneys and accountants very busy. If the past is any indication, there is likely to be a massive rush of business and individuals searching for new loopholes to take advantage of.

“Nobody knows what to do,” said real estate attorney Pierre Debbas of Romer Debbas while negotiations were still ongoing.

“If it’s permitted by the IRS, I would convert to the corporation the next day,” he said, referring to the Manhattan-based law firm he co-founded.

Keller Williams’ Chin agreed but noted there are hurdles that prevent many businesses from doing so.

“If you can get your income to be taxed as a corporation — that would be glorious,” he said.

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated that Greystone restored a multifamily building in Newark. The property’s restoration work has been financed, but is not yet complete.