UPDATED April 3, 11:32 a.m.: In recent years, Long Islanders have been in the process of rethinking the notion of suburbia, shifting from a vision of green lawns, white picket fences and quiet streets lined with single-family homes to a more modern image of bustling residential communities built around vital town centers. The denser living that was said to be Long Island’s future is now its present, as the youngest and oldest families increasingly look for a new way of life that may not include a mortgage.

Multifamily housing projects are by far the most popular type of endeavor on the Island, according to The Real Deal’s analysis of data compiled by CoStar. These new builds make up about 81 percent of the total square footage under construction by Long Island’s top 10 developers in the fourth quarter of 2017, the data showed.

The added availability of high-quality rentals appeals to many would-be buyers, and developers are racing to bring more units to the market to meet demand.

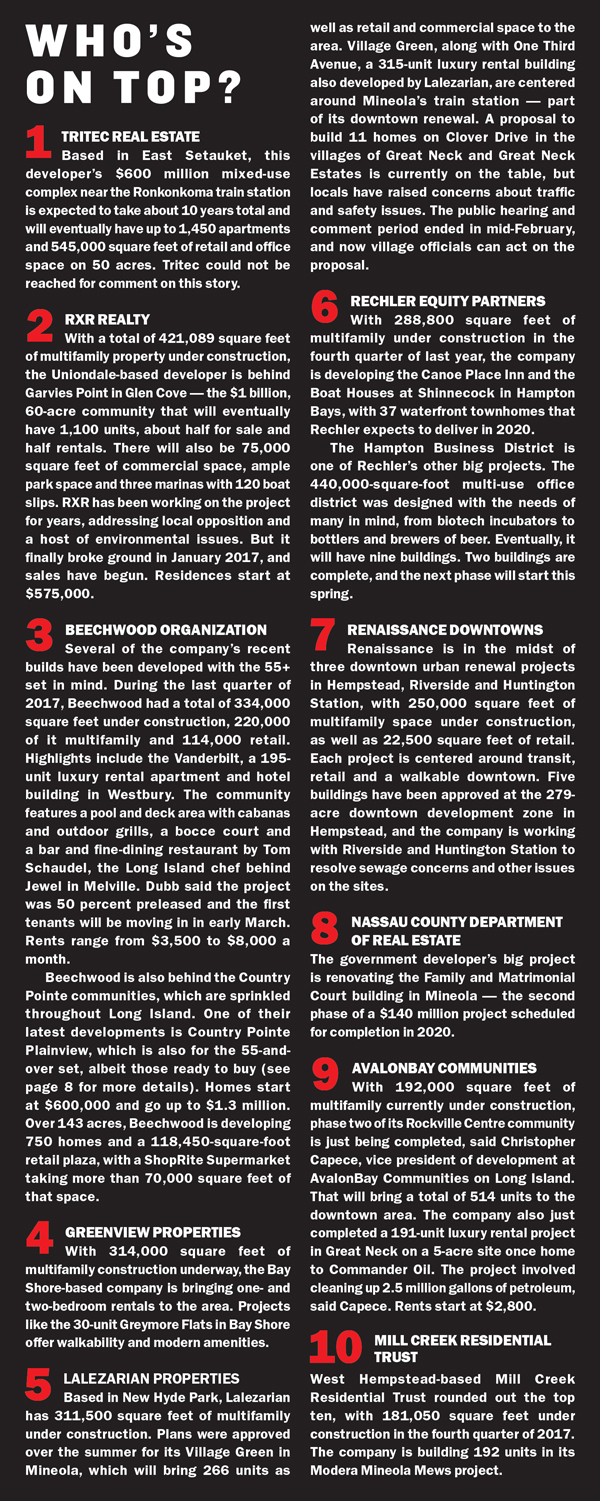

“There’s more need than we can supply of that product,” said Steven Dubb, principal at the Beechwood Organization, which came in third in TRD’s ranking of top Long Island developers. The ranking analyzed data on the square footage of under-construction projects as of the fourth quarter of 2017 with a rentable building area of at least 10,000 square feet in Nassau and Suffolk counties, as recorded by CoStar. Condo projects were excluded. Tritec Real Estate had the most square footage under construction, with the first phase of its Ronkonoma Hub project — made up of 477,300 square feet of multifamily space — breaking ground in November 2017. The firm could not be reached for comment.

Older Long Islanders are often looking to downsize and spend less time on caring for a home, Dubb said. Or they could be on the verge of retirement and possibly relocating, but still want a place out east. Demand for rental properties in age-restricted homes has increased, and companies are going after it with projects offering an active lifestyle and little upkeep.

On the other side of the age spectrum, some millennials have reservations about taking on homeownership. Having seen their parents get burned during the recession of 2008 and 2009, many young professionals are happy to just keep renting, according to some developers.

Of the housing stock on Long Island, currently only about 17 percent consists of rentals, developers said, compared to about 40 percent in other suburban markets like New Jersey and Connecticut.

And in other sectors, like retail, much of the space is being created to support these new communities. Even companies that have made their bread and butter on office and industrial developments are getting into the multifamily game.

The rise of multifamily

Anyone following Long Island’s multifamily developments understands that it has been fueled in part by millennial families moving east after years in Manhattan or one of the boroughs. They still work in the city and are looking for space and convenience, but also a slightly more chic lifestyle than what a standard single-family home in Nassau County can offer.

Many developers have been focused on properties close to downtown train stations, like in Hempstead, Great Neck and Mineola. However, Rechler Equity Partners is more interested in its housing developments being close to the highway, according to Gregg Rechler, managing partner of the Plainview-based company (and brother of RXR Realty CEO Scott Rechler). He said Rechler — which placed sixth in TRD’s ranking — is designing apartments for Long Islanders who also work out east.

“Many young people have negative feelings toward homeownership,” he said, noting that the Great Recession has made them reluctant to sign on for 30 years of mortgage payments. At the same time, they want space, full-blown amenities and park-like outdoor areas, Rechler added.

Christopher Capece, Gregg Rechler and Steven-Dubb

Enter projects like Greybarn in Amityville, which will eventually add 500 apartments to the area. Phase one was completed in October 2016, and phase two is almost complete. One- and two-bedroom units there are now renting at $2,325 and $2,800, respectively. Construction of phase three is also underway.

Rechler Equity has been developing office and industrial space on Long Island for 60 years, and Rechler claims that its buildings are 99 percent occupied. The company started exploring multifamily developments to help house the employees of companies that were tenants in their buildings.

“There’s a well-paid workforce that supports all that space,” Rechler said. “We found that 80 percent of those workers live on Long Island.”

Playing off the local architecture and appealing directly to Long Island natives has worked for Rechler. Its residents are “one-half millennials, one-half baby boomers. Everyone in the middle owns a house.”

Rentals may also prove more popular under the country’s new tax laws, which cap mortgage and state and local tax deductions. With Long Island’s expensive properties and heavy tax burden, some families may find renting less expensive in the long run, experts said.

The long path to approval

Developers have been working to create these amenity-filled, transit-oriented housing projects for years. While they have identified an untapped market, delivering pristine multifamily projects has been stymied by the vocal opposition of locals and the area’s notorious labyrinthine approval process, although some note that it has improved a bit in recent years. Projects can take decades. A four- or five-year build is considered fast — “for Long Island.”

Rechler remembers attending one meeting for a site-plan approval with a handcart in tow. “We had eight boxes of files,” he said.

And there’s good reason for all the rigmarole. Long Island has been an infill community for decades, and its infrastructure — especially its sewage system — is aging. If they are planning to move more people in, developers first need to address how the build will not only support the new residents, but also potentially help those already there. “You have to get creative in dealing with that,” Rechler said. Infrastructure issues drive “every decision on every site. Every time you evaluate anything, you evaluate sewage treatment first.”

Long Island natives have also been very vocal about not wanting these kinds of developments. Some think it was Long Island’s deteriorating apartment buildings that gave residents the wrong idea. People saw those outdated rentals and didn’t want to encourage more of that kind of housing.

“The older 1950s and 1960s product gave people a preconceived notion about rentals, and it’s taken some time to convince people,” said Christopher Capece, vice president of development at AvalonBay Communities on Long Island, which placed ninth in TRD’s ranking. “We are just starting to see high-quality product on the market.”

On the other hand, the addition of apartment-style homes, especially those more than a few stories, used to be “considered very scary” by many suburban dwellers, Beechwood’s Dubb said. But he agreed that once they saw some of the finished product, resistance softened a bit.

“The NIMBY-ism that was so strong in the late 1990s and early 2000s has abated a little bit,” he said. “Or it has been matched by people who are frustrated by the lack of housing options. …There’s definitely a population on the Island willing to be more vocal now.”

The rising costs to build

More recently, a rise in construction costs has started to give developers more pause about where to stake their claims.

“Softwood lumber is at record high [prices], which negatively impacts construction,” Capece said. New tariffs have pushed up prices since last April, when President Donald Trump approved an increase in duties on lumber from Canada, which supplies more than a quarter of what’s used in the U.S. each year. Those duties can be as much as 24 percent.

Developers have had to absorb the costs. In mid-February, prices were about $528 per 1,000 board-feet for lumber shipped from Canada. That’s up from an average of $278 in 2015 and $401 last year, according to reports.

That’s not all: Materials like metal and concrete have also become more expensive, developers said. In addition, after last summer’s season of disastrous hurricanes and wildfires, a lot of resources have been redirected to Southern and Western states. Finally, local subcontractors are in demand and are therefore able to charge more, so labor costs have increased as well. “We can’t pass all that on to homebuyers, so we’re stuck in the middle,” Dubb said.

That makes decisions about whether or not to take on a new development a bit more difficult. “We wonder more than we used to if we can make money from a project,” said Dubb. “We let things go where we may not have before.”

Despite the challenges, developers think there’s room for more development on Long Island, especially multifamily. “The dearth of quality housing on Long Island is still there,” said Capece.

And the demand is still there, too, developers said. Multifamily projects are crucial for keeping both younger workers and the Island’s aging baby boomers in the area. Keeping them out east means giving them updated housing and office space options. Rechler doesn’t think Long Island will meet that demand anytime soon, especially since each project takes so long: “It’s going to take a lot of time and energy.”

Correction: This ranking has been updated to include Mill Creek Residential, with 181,050 square feet of under construction, in the 10th spot.