Young Hollywood partying on blue Astroturf by the pool on the Sunset Strip. X-rated exhibitionism towering over the High Line. Trendsetting design, middlebrow cool, the Boom Boom Room. For the past two decades, the Standard Hotel has helped define what the good life looks like.

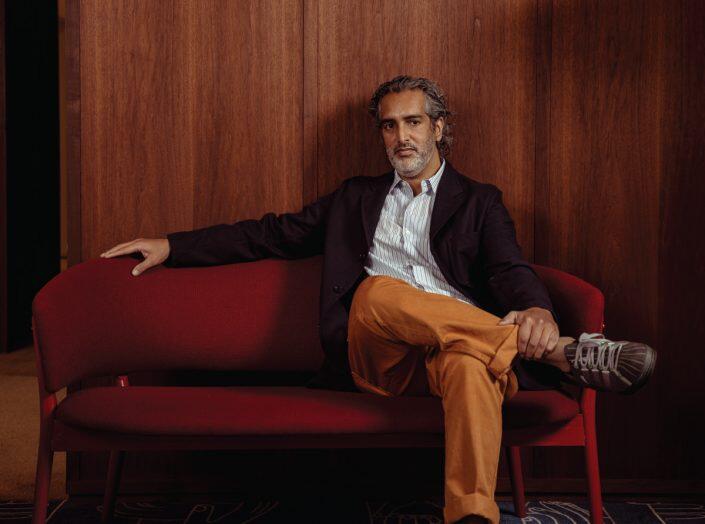

Scaling that boutique sensibility is a challenge, and it’s one Amar Lalvani has spent the past decade working on. Lalvani, who is part-owner after taking over Standard International from André Balazs in 2013, may at first glance seem to be the antithesis of the hotel’s playboy founder.

The son of immigrants who grew up outside Los Angeles in the 1970s, Lalvani runs the Standard empire with laid-back, SoCal-cool vibes.

“Look, as you’ve noticed from everything I’ve said about my career, there’s no plan. That can be disconcerting to people,” the 47-year-old told The Real Deal during an interview at the company’s Noho offices in February. “As long as we enjoy it, as long as we’re doing well, as long as there’s demand for what we do in a certain city and it gets us excited, we’ll do it.”

Lalvani started out working for Barry Sternlicht’s Starwood Property Group in 1998, when the company became the nation’s largest hotel owner with the $15 billion purchase of ITT Sheraton.

He went to work for Balazs in 2011. Two years later, with backing from investors including then-Philadelphia 76ers part-owner David Heller, he bought Balazs out. Since then, he’s taken the business from five hotels to 20 in places such as London, the Maldives, Bangkok and Ibiza. And 15 more are on the way.

If L.A. and New York were the epicenters of hip in the early aughts, Lalvani has steered the company toward today’s cultural hotspots. In 2015, Standard bought a majority stake in Bunkhouse, a chain of boutique hotels based in Austin, where Lalvani keeps a second home. And he’s launched One Night, a last-minute hotel booking app.

He’s now ready for his next role: In October, Lalvani took on the title of executive chair, appointing company President Amber Asher as CEO.

Lalvani spoke with The Real Deal about working with industry titans, bouncing back from a devastating lawsuit and scaling the Standard brand.

Born: May 15, 1974

Lives in: Tribeca

Hometown: Diamond Bar, California

Family: Engaged, Two children

Your résumé reads Wharton, Harvard, Starwood, Blackstone … that’s about as institutional as it gets. How do you go from that to leading a brand that’s all about thumbing your nose at the man?

I think that thumbing the nose was always inside me. And that’s actually somewhat my comfort zone. I grew up in a fairly typical immigrant family. For my father, it was very much about the academics. It was very much about being buttoned up. So maybe there was some frustrated creative artist inside as I went through the motions at Wharton and Harvard.

What did your parents do?

My father was born and raised in New Delhi, and he moved to the U.S. in 1961. Of course, I heard the story a million times: He came with $21 in his pocket. The only place that would give him a full scholarship including stipend was in New Brunswick, Canada, so he moved there on his own.

When he went back to India to find a wife, he moved her from Bombay — where she was having a great time in art school — to Bartlesville, Oklahoma, to work for Phillips Petroleum. It was a company town; all the men wore the same suits, and we still have this paper — I think it was the Bartlesville Post — it said, “Indian man brings wife to Bartlesville.” My mom cried herself to sleep every night.

What was it about real estate that made sense to you?

It was super intuitive to me: the supply-demand dynamics, how things get built, what moves in the market to a point where values exceed construction costs and that’s when you get built.

What did you do after you graduated?

I got two offers that I was interested in. One was at Starwood Capital and one was at the investment bank Jefferies, which was headquartered in L.A. at that time. In the mid-’90s everybody wanted to be an investment banker and I really wanted to go back to L.A., so I took the job at Jefferies.

Did you work with [Jefferies CEO] Rich Handler while you were there?

I didn’t — Rich was head of capital markets and trading, and I worked on the investment banking side. He was a legend at that time already, and I had one experience with him. We used a lot of high-yield bonds back then, and apparently it’s a rite of passage that you get a call when you price your first deal.

I picked up and he said, “This is Rich Handler. What’s the yield on it?”

I do it on my computer and I say it’s 8.73 percent.

He says, “You better be fucking right or I’m going to kill you,” and he hangs up.

Were you intimidated?

Oh my god — you can’t imagine. Jefferies was a wild place. It was kind of the last vestige coming out of that junk bond era.

The culture was intense. At that time people still prided themselves on how hard they worked and how many hours they worked. We would get into the office at 7; oftentimes, we’d go till 2 in the morning. I talk to my daughters now and I tell them those stories and they think I’m dumb. “Why on earth would you do that?” they say. I said, “Well, I guess we’re sitting here now because I did all that stuff.”

How do you feel about work-life balance today?

I’ve learned over the years how important that is, and I respect it a lot. When I left Starwood for Hilton, I got hit with a major lawsuit and it changed my whole worldview. I saw that when there’s a crisis situation, no matter how good a job you’re doing — no matter how well respected you are — everybody runs for the hills and they put themselves first. I think coming out of that experience I had a ton of respect for people who take care of themselves.

It’s got to be hard to find that balance in the hospitality business. Is the jet-setting and late-night parties stuff work for you, or is that the life part?

The way I think about it is, I’m in it but I’m not of it. I’m deep in it because I love creating stuff that people like. I love creating hotels that people like, restaurants, nightlife, I love other people enjoying it. Doesn’t mean I don’t enjoy it, but it’s not my thing. Maybe it’s like creating a piece of art that you enjoy watching people enjoy and you enjoy the art of creating it, but not necessarily yourself enjoying that piece of art.

What happened with the lawsuit?

Barry [Sternlicht] left [Starwood Hotels] and it became a little weird; Starwood wasn’t that interesting. They wanted to take W and split it up and me to be the head of all North American development for all the hotels, but I had no interest in doing Four Points and Sheratons.

At that time, Blackstone was buying Hilton and I got an offer, so I moved out to L.A. to launch this new boutique brand and within a year we got hit with this major lawsuit, front page of the Wall Street Journal. I lost everything; I lost all my equity, all my salary. I was living in L.A. with two young kids and I had to get my own lawyer. It all worked out in the end, but I moved back to New York and I had literally left with nothing at all — not even my reputation.

Was the conflict with Barry?

No, this was the new management, and I think they desperately didn’t want Hilton to compete with W, which I understand.

So I came back to New York and I got a call from André Balazs. I’d met him once on a plane. He said, “Can we have lunch?” He was really sweet. He said, “I’ve talked to a lot of people in the industry, and I think Standard has a lot of potential to be a global brand. And I’ve heard that you are the person that we would work well together to make it a global brand.” He was quite convincing.

How did you come to own the business?

I worked for him for a couple years and then realized it wasn’t going to work like that. We had a good relationship, but it was his company. If we really wanted to do it, we needed to build sales and revenue management and technology. And you can’t just build cool stuff and hope it works all around the world.

It was his company, and the investment wasn’t there to build that infrastructure. And he did business differently than I do. So I thought it was better that we leave on good terms than just continue that way. So I left at the beginning of 2013 and I did a bunch of random stuff. I opened some restaurants in New York.

Then André came back to me and he said, “Look, I’m ready to move on with my life in a certain way. Do you want to come and be the CEO of the company and take it on?” I said, “I’d like to do that, but it’s got to work a different way. It’s still your company. We need to raise outside capital. I need to be in control, and you need to be bought down to a minority position.”

You’re doing branded condos now. Do you ever worry about taking that cachet that you’ve built and handing it over to someone else?

No, because even when we go into the residences or condos that we’re doing, they’re coming from the same spirit. The three places we’ve done residences are the three places that I personally would want to live: Lisbon, Miami and Austin. It’s like, “We love this market. We could see why we’d want to live in this market.

What if you had a branded building and something out of your control happened, like shoddy construction?

Most hotel companies, including ours, don’t own the real estate, so we’ve always had to deal with the dynamic of: We have control over certain things, we don’t have control over other things. Most times in real estate you say, “location, location, location.” Quite honestly, for us, it’s “partner, partner, partner.”

In the Meatpacking District, Gaw Capital is facing foreclosure. How does that affect things?

Gaw has been a great partner. They’ve been supportive all throughout the crisis. We separate ourselves from those real estate issues. That’s between them and their lenders. And we certainly trust them to handle it as they see fit. From a purely management and contractual perspective, we have what’s called a nondisturbance agreement. So whatever happens in that matter, the Standard will still be there.

What do you do to relax?

I ride my Peloton.

What do you think about the struggles they’re going through now?

Full disclosure, [former Peloton CEO] John Foley is my best friend from business school. I was a seed investor and I was on the board early on. I’m probably biased, but I don’t think there’s a tech company that I can think of in the world that every day makes people healthier, that makes people feel better about themselves.

They couldn’t get the bikes out fast enough so they invested in manufacturing, and in retrospect you can see that they maybe overinvested. But I put it in perspective, and I have every confidence that’s going to the next level.

What do you splurge on?

I never cook, so I go out to eat dinner every night or order in something good. I like mezcal, I like a nice whiskey. When my daughters want to go to a concert or a festival, I get nice tickets. I don’t buy stuff. I think life’s short and the enjoyment is what it’s about.

What made you realize it was time to step aside as CEO?

Like everybody, coming out of Covid you think about what the next phase looks like. And to open 15 hotels around the world, maybe more, in the next five years would necessitate me being on a plane the entire time. And I’ve done that for a long time, and it’s exhausting. I have two teenage daughters at home who are not going to be at home that much longer.

Amber Asher was our general counsel for seven years and the president of the company for three years. She’s taken on the role of CEO. It’s important to give people opportunity when they’re ready. And I’m very proud that she’s 100 percent the right person for the job, but that she also happens to be female.

Do you have a sense of what you want to do with your free time now?

No. You don’t know truly what you want to do until you get a little bit of distance. So I read a ton. I listen to a ton of podcasts. I learn, I learn, I learn. And then, only then, my mind will open up to what’s next. It’ll be connected to this. I’m still deeply involved in this, but I think about how this business ultimately gets transformed for the next 20 years — how this industry gets transformed — I think I’d like to figure that out, but I’m not there yet.