A partially built condominium in Manhattan’s Financial District cuts a melancholy figure on an overcast Saturday in August. The front of the building, an exposed checkerboard of unfinished apartments, stretches 912 feet upward into a fog of gray cloud. Two security guards mill about on the deserted pavement opposite.

Construction at 125 Greenwich Street has been stalled for months, and the developers, a group that includes Davide Bizzi’s Bizzi & Partners and Howard Lorber’s New Valley, are on a mission to see it over the finish line.

That may be tricky: The project is deep in debt, and two foreclosure actions filed before the pandemic hang over it. Sales were expected to begin closing by June 30. When that didn’t happen, Michael Feldman of Romer Debbas said, four of his clients who had bought units in the building took the developers up on an offer to rescind their contracts.

The luxury development, with 273 units priced between $1 million and $6 million, is one of many in Manhattan that launched sales after the heady days of the condo boom passed, adding to a glut of high-end properties across the city.

Though Manhattan’s depleted luxury market is beginning to flicker with small bursts of activity, it may not be enough to save some projects from becoming distressed investment opportunities. That’s especially true for projects that struggled before the economic crisis.

“The pandemic really heightened awareness, because lenders started looking at things a little bit more closely,” said Stephen Kliegerman, president of Brown Harris Stevens Development Marketing. “Projects that were already thin or even underwater, pre-Covid, all of a sudden the fire alarm went off and people started to really worry. If they weren’t doing well pre-Covid, how are they going to do coming out of Covid?”

“The pandemic really heightened awareness, because lenders started looking at things a little bit more closely,” said Stephen Kliegerman, president of Brown Harris Stevens Development Marketing. “Projects that were already thin or even underwater, pre-Covid, all of a sudden the fire alarm went off and people started to really worry. If they weren’t doing well pre-Covid, how are they going to do coming out of Covid?”

Deals on ice

When the pandemic froze Manhattan’s luxury market in March, it did not discriminate. Deals for properties priced above $4 million fell across the borough to an average of just four per week, according to Donna Olshan of Olshan Realty, who tracks luxury sales.

After the state allowed brokers to start showing homes again in June, luxury deals picked up to an average of 11 per week — still far from a total recovery and well below the average of 18 in 2019. The total number of luxury contracts signed in Manhattan between January and the first week of October fell 40 percent from the same period last year.

The climate has forced embattled developers to consider their options, which include securing more financing, selling units to bulk buyers and bringing in new partners. But with so much uncertainty, lenders have further retreated from high-end condos, driving up borrowing costs.

Read more

The problems at 125 Greenwich predated the pandemic. Last summer, the developers defaulted on loan payments and construction bills, triggering a foreclosure action from United Overseas Bank, which subsequently sold the debt to investment firm BH3.

After the developers defaulted, Nicholas Mastroianni, whose EB-5 fund had $194 million in the project, enlisted brokers from Newmark Knight Frank to market the debt in a UCC foreclosure auction, but one never materialized. Mastroianni declined to comment on why.

In February, Fortress Investment Group purchased the tower’s defaulted mortgage from BH3 for about $230 million, inheriting the foreclosure action. A person familiar with the development said they anticipate Fortress will “continue on with the foreclosure and potentially work out a deal with the sponsors as well.” Fortress declined to comment.

Patrick Fitzmaurice, a partner at law firm Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman who represents lenders and creditors but is not involved at 125 Greenwich, said it’s not unusual for a development to have a UCC foreclosure and a foreclosure lawsuit levied against it at the same time; different lenders have different priorities and timelines.

Fitzmaurice said lenders in Fortress’ position can “continue negotiating with the borrower and any other interested party” until the end of the foreclosure process, and there’s “always the possibility of a deal.”

But new financing for the development remains elusive. Talks with Silverstein Capital Partners last year about a possible capital infusion or recapitalization collapsed because the parties could not reach an agreement on terms, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Ran Eliasaf, managing partner of Northwind Group, which recently launched a debt fund that offers condo inventory loans and rescue deals, said the firm received a package of materials about financing 125 Greenwich that was circulating last year, but decided against it because “it doesn’t meet our fund’s criteria.”

“We always felt that the luxury market was saturated and there’s not enough buyers out there for so much supply,” Eliasaf said.

Bizzi and New Valley declined to comment, but a recent amendment to 125 Greenwich’s offering plan says the sponsors are still “in active negotiations” for new financing.

Going once, going twice

The tower at 125 Greenwich is far from alone in its woes.

For several months, Ceruzzi Properties has been looking to refinance, sell or do bulk deals at its Hayworth condominium at 1289 Lexington Avenue, which has struggled to move units. In September, Newmark Knight Frank started shopping the junior mezzanine positions of four HFZ Capital condos. And in October, JLL began marketing a UCC foreclosure sale on Wonder Works Construction’s Vitre condo at 302 East 96th Street, where 40 of 48 units remain unsold after two years on the market.

“For the first few months of the pandemic and after things shut down, what you saw was lenders really working with borrowers and either deferring interest, deferring principal, [or] deferring principal and interest,” said Michael Lefkowitz of law firm Rosenberg & Estis, who represents real estate clients in both the equity and the debt spaces. Now, he said, “I think you’re seeing less cooperation in that regard.”

“For the first few months of the pandemic and after things shut down, what you saw was lenders really working with borrowers and either deferring interest, deferring principal, [or] deferring principal and interest,” said Michael Lefkowitz of law firm Rosenberg & Estis, who represents real estate clients in both the equity and the debt spaces. Now, he said, “I think you’re seeing less cooperation in that regard.”

“[Lenders] understand there’s a bigger problem here,” Eliasaf said. “It’s not like the developers did something wrong, necessarily, and it’s not like the banks will get the keys and do a better job selling.”

Still, there are limits. “You can’t work around a basis issue,” he said, referring to the costs developers and lenders put into projects. “If your basis is $2,600 a foot and you’ll sell units at $2,000 a foot, your equity is wiped.”

Fitzmaurice said that while he has been hearing a lot of talk from lenders about pursuing foreclosures, he hasn’t seen much action so far.

“I think there’s a few different reasons for that,” he said. “Some of it is the nature of the pandemic and the uncertainty that exists with when values are going to stabilize, and where they’re going to stabilize, and how long it’s going to take.”

There are also logistical considerations: Since the pandemic hit, New York state has put restrictions on initiating foreclosures and there have been several complaints filed by debtors facing UCC foreclosure auctions. In one such case, a New York judge delayed an auction from going forward because it would not be “commercially reasonable” to do so.

Fitzmaurice predicts the market will probably see more foreclosures in the next six months or so.

“There are defaults all over the place,” he said. “Eventually, there just has to be [foreclosure] activity when you have those circumstances. Particularly where nobody knows when it’s going to be better.”

Still, whether because of pragmatism or bravado, some in the industry insist the crisis has separated the wheat from the chaff: If investors are looking for distressed opportunities, they won’t find those in premium buildings with stable finances, but in developments with too much debt, unrealistic pricing or crummy designs.

“As a developer and as a native New Yorker, it’s tough to see the challenges in the market before coronavirus and now after coronavirus, but in some ways it’s one of those things where the cream rises to the top,” said Evan Stein, president of development firm J.D. Carlisle, which is currently building a 199-unit condo at 15 East 30th Street in NoMad.

To Kliegerman, the situation feels a lot like 2008, when the financial crisis left many developers similarly exposed. “Everyone realized that the emperor didn’t have clothes on in many of these projects,” he said.

Both Lefkowitz and Fitzmaurice anticipate there could be deeper distress this time around, in part because there are more unsold apartments on the market.

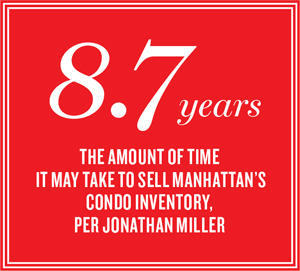

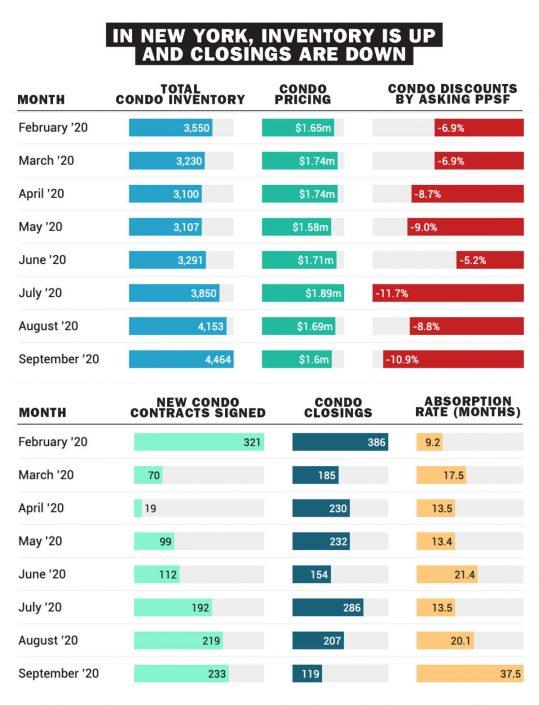

Though luxury inventory right now looks similar to what was on the market during the financial crisis — 1,600 listings in the third quarter this year versus 1,623 in the third quarter of 2008 — there is much more high-end “shadow inventory” today. Appraiser Jonathan Miller of Miller Samuel predicts the current crop of unsold new-development units across Manhattan will take 8.7 years to sell, compared to 3.5 years in 2008.

Northwind’s Eliasaf argues that the outlook this time around is more optimistic. During the pandemic, the stock market has performed well, he said, and investors have cash to spend.

“I think it’s going to be very specific,” he said. “You’ll have specific buildings, specific properties, specific owners that will have serious issues, and you’ll have others whose portfolios are more well-balanced that will be okay.”

The New York puzzle

While many of the condo market’s pain points manifested before the pandemic, what happens going forward will depend on New York City’s broader recovery.

Schools have largely reopened, and some of the wealthy residents who retreated to the suburbs have returned. But unemployment remains twice as high as in the rest of the country, and the vast majority of office workers are still working from home.

“It’s all part of the same puzzle,” said Lefkowitz. “If we were to have a second wave and we have a slower return to the office, a slower return to normal activity, this will likely result in increased activity on foreclosure.”

In the once-bustling Financial District, 125 Greenwich Street remains in limbo. The building, which topped out last March, was just 68 percent complete as of December, according to a financing prospectus obtained by The Real Deal. No listings are currently on the market.

“I think it was always an ambitious project, both construction-wise and pricing-wise, for that neighborhood,” said Eliasaf.

The condo is now expected to begin its first year of operation in January, according to the latest amendment to its offering plan. Whether that happens, however, is as uncertain as everything else.

In the meantime, there are plenty of investors, both private and institutional, looking for opportunity. The appeal of a distressed condo note is the value investors believe they’re getting, according to Lefkowitz.

But what is value in such a prolonged crisis, with normal life upended and the real estate market likely scrambled for years to come?

“That’s the big question,” he said.