Defaulting on a real estate loan can be ugly. But how a borrower defaults can determine whether they can maintain their relationships with lenders and get back in the game. Here’s an inside look at what worked and what didn’t for four high-profile developers.

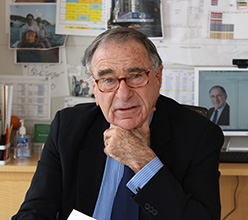

Harry Macklowe

It’s well known that Macklowe revered Zeckendorf. Given his similar appetite for risk, that’s not surprising.

In 2007, Macklowe famously bought a portfolio of Manhattan office buildings from the Blackstone Group for $7 billion. He financed a staggering 99 percent of the purchase price with one-year loans from Deutsche Bank and Fortress Investment Group. The $1.2 billion loan from Fortress reportedly carried a sky-high interest rate of 15 percent and was collateralized by his entire portfolio, including the GM Building, his crown jewel, and the Drake Hotel.

A year later, when his loans came due, the market had turned and Macklowe was unable to refinance. But instead of fighting the lenders and filing for bankruptcy, Macklowe cut deals: He handed the recently purchased office portfolio over to his senior lender, Deutsche Bank, and sold the GM Building to pay off the Fortress loan to the tune of $2.9 billion. His default made headlines, but his reputation in the industry, and among lenders, survived.

Harry Macklowe

“His mistake was not the price he paid … it was the way he financed it,” Blackstone’s real estate head Jonathan Gray was quoted as saying in Vicky Ward’s book “The Liar’s Ball.”

Even though Macklowe has twice defaulted on major loans — he lost the Hotel Macklowe near Times Square to his lenders in the 1990s — he has once again risen from the ashes.

In 2012, Macklowe and his equity partner CIM secured a $400 million construction loan from UK-based hedge fund Children’s Investment Fund for their condo tower 432 Park Avenue, which is now among the most highly coveted luxury residential towers under construction in all of New York.

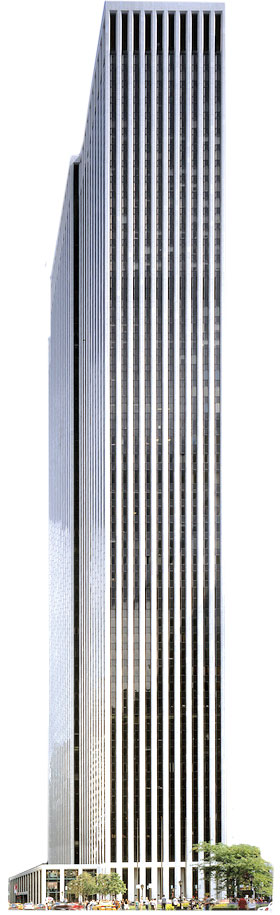

The GM Building

In an April interview with TRD, Fried Frank attorney Michael Barker, who represented the Children’s Fund on the deal, explained that the fund was attracted to the market here. “New York real estate is seen as an increasingly solid investment,” said Barker, who declined to comment on the deal specifically. “It has survived ups and downs throughout its history.”

Moreover, the loan is structured in a way that leaves the Children’s Fund with little risk and high returns. It covers a mere 40 percent of the project’s cost and yet still carries a whopping interest rate of around 10 percent, according to sources. As a comparison, Vornado Realty Trust’s construction loan from Bank of China for 220 Central Park South carried a floating interest rate of 2.92 percent, according to public filings — although the REIT likely borrowed against its sizeable balance sheet.

More recently in 2014, Macklowe, who could not be reached for comment, bought the former Bank of New York headquarters at 1 Wall Street for $585 million. And he financed it with a $460 million loan from the lender he defaulted on in 2008: Deutsche Bank.

Lost in the headlines was also the fact that Macklowe has had considerable success with some of his projects. For example, he brought the iconic Apple Store to the GM Building’s public plaza, which helped drive up its value. Five years after buying the tower for $1.4 billion, he sold it for $2.9 billion.

Bruce Eichner

Like Macklowe, Bruce Eichner has twice defaulted on major loans. But unlike Macklowe, he fought his lenders in bankruptcy court.

In 1991, in the midst of a major market downturn, Citibank moved to foreclose on a construction loan for Eichner’s 1.1 million-square-foot office tower 1540 Broadway, after the developer defaulted.

According to Jerry Adler’s 1994 book “High Rise,” Eichner responded with a barrage of countercharges, accusing the bank of acting in bad faith and refusing to restructure the $250 million loan on the building, now home to media giant Viacom, Yahoo and others.

In 1992, Eichner’s company Broadway State Partners entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy and used the financial protection to sell the building for $119 million to German publisher Bertelsmann (whose name later gave the building a temporary moniker). That sale meant that Citibank lost around $130 million on the loan, which did not sit well with the bank’s executives.

Still, Eichner continued developing in New York, building the Brooklyn Heights apartment high-rise 180 Montague Street. Eichner later shifted his focus to Miami and Las Vegas, where he developed the city’s most expensive casino ever, the Cosmopolitan, in the early 2000s. But when the market turned in 2008, Deutsche Bank foreclosed on a $768 million construction loan and took over the casino.

At the time, Eichner told the Wall Street Journal that he was a victim of the market and that lenders would soon work with him again. “It’s probably pretty safe to say that somewhere in 2009 or 2010, Bruce Eichner will surface with another one, something,” he said. “There’s zero that will stick to my shoes.”

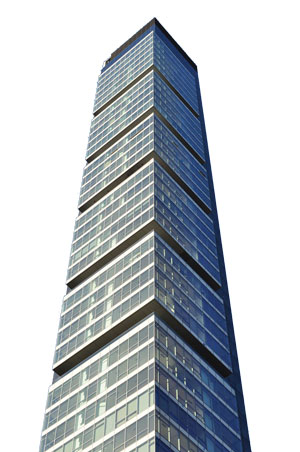

His prediction turned out to be dead on. He is currently developing the 777-foot condo at 45 East 22nd Street, backed by a $340 million construction loan from Goldman Sachs and an $80 million investment from Dune Real Estate Partners and Fortress. “None of that is dumb money,” star broker Dolly Lenz, who sold units in nearby condo tower One Madison, told TRD in February. “In fact, I’d venture to say it’s some of the smartest money on the planet. That’s comforting to me and it’s comforting to buyers.”

As of last month, more than 50 percent of the building’s units, which go as high as $38 million, were sold. “If developers with proven track records can show they can make money, banks will come back to them,”Ken Weissenberg, co-chair of the Real Estate Services Group at accounting firm EisnerAmper, said of Eichner.

Kent Swig

Kent Swig’s 2008 default has plenty of drama. At one point, developer Yair Levy, his estranged partner, allegedly struck him with an ice bucket. Meanwhile, his father-in-law, Macklowe, briefly helped him with a personal loan. But that relationship unravelled after Swig and Macklowe’s daughter Liz divorced months later.

Much like Macklowe and Eichner, Swig was the victim of bad timing.

In 2003 and 2004, he bought four Downtown office buildings — 5 Hanover Square, 44 Wall Street, 80 Broad Street and 110 William Street — for a combined $350 million. And in 2005, he teamed up with Serge Hoyda and Levy to buy the Sheffield on West 57th Street for $418 million.

As the market soured, he took out personal loans to cover his costs but was soon forced to default. In 2008, his lender Square Mile sued him for nonpayment and won a $32 million judgment.

Other lawsuits dragged on. For example, he sued JPMorgan in an ultimately failed attempt to stop the lender from foreclosing on 90 Broad. Eventually, he reached a settlement with his lenders. He’s also a principal of Terra Holdings, the parent company of brokerages Brown Harris Stevens and Halstead Property. And he still holds stakes in several New York City buildings, according to Swig Equities’ website.

Other lawsuits dragged on. For example, he sued JPMorgan in an ultimately failed attempt to stop the lender from foreclosing on 90 Broad. Eventually, he reached a settlement with his lenders. He’s also a principal of Terra Holdings, the parent company of brokerages Brown Harris Stevens and Halstead Property. And he still holds stakes in several New York City buildings, according to Swig Equities’ website.

In a 2010 interview with TRD, Swig claimed that he struck a deal with Fortress to be the “fall guy” in the press in exchange for future profits at the Sheffield. It’s unclear what those profits amounted to, if anything, and Swig did not respond to calls for comment.

But his lengthy legal battles have slowed his recovery from the crisis, and Swig has yet to launch a major new project.

Still, the developer has a lot of admirers in the industry, and many expect him to make a comeback. “Ultimately Kent is the kind of person who will rise up above it all and move forward with his life,” developer Larry Silverstein told the New York Times last year.

Ira Shapiro

The luxury condo development One Madison was meant to be Ira Shapiro’s big break, turning a developer of low-key affordable housing in the outer boroughs into a Manhattan real estate star. Instead, it turned into a disaster, derailing his career before it really started.

Today, One Madison is in the hands of the Related Companies and HFZ Capital, while Shapiro has struggled to get back on his feet.

Once again, bad timing played a role.

Shapiro and his then-partner Marc Jacobs began building the tower in 2007, backed by a $240 million loan from iStar Financial and $60 million from other investors. By the time sales launched, the real estate market was in free fall. Soon, the developers struggled to pay their bills. But rather than swiftly handing over the property to iStar, Shapiro tried to scrap together money in every way he could. Lawsuits brought by several investors claimed he did so in violation of contracts, such as offering discounted apartments in exchange for loans, a violation of his agreement with iStar, and forging Jacobs’ signature. (Jacobs later left the partnership.)

A last-ditch effort to save his stake in the project with the help of none other than Eichner fell flat. In 2010, Shapiro declared (non-personal) bankruptcy for the project and eventually lost One Madison.

Shapiro’s most recent attempt to get back into the real estate game highlights how much his bankruptcy still haunts him. In August 2014, the developer announced plans to build condos on the site of a church at 361 Central Park West. “Boom time developer is back in action,” read the headline in The Daily News. The claim proved premature. Ten days later, TRD reported that Shapiro had offloaded the site to his sister, Irene Shapiro. According to sources, the developer had struggled to get financing and was still facing claims from One Madison creditors, leading him to downplay his role in the new project. In May, the local community board rejected the redevelopment plans.

Five years after declaring bankruptcy, Shapiro’s real estate career is still in limbo.

“I think Macklowe has nine lives,” said a high-profile New York real estate attorney who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “Ira Shapiro — he’s just had one life.”