Howard Michaels, the tough-talking finance broker, shot off an email in 2014 to his client Michael Shvo.

Howard Michaels, the tough-talking finance broker, shot off an email in 2014 to his client Michael Shvo.

Michaels, who heads the Carlton Group, had just gotten off a long phone call with Nicholas Mastroianni II, the head of the U.S. Immigration Fund, New York’s biggest EB-5 regional center, and was convinced that EB-5 money from Chinese investors was the perfect financing solution for Shvo’s planned 275-unit condo at 125 Greenwich Street in Lower Manhattan. “[It] sounds like legalized crack cocaine,” he raved to Shvo, according to an email later revealed in a lawsuit between the two. “You guys would be crazy not to jump on this.”

The developer agreed, eventually securing an EB-5 loan that came in the form of $175 million in mezzanine financing.

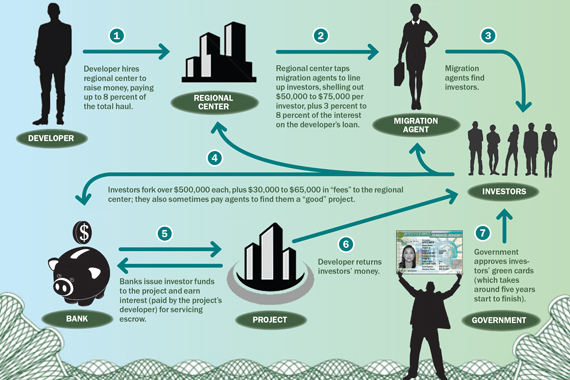

Shvo is certainly not the first high-profile developer to milk EB-5 as a source of cheap capital. The program, which grants foreigners a U.S. green card in exchange for a $500,000 or $1 million investment, has become wildly popular — and controversial — in the last few years.

It’s also birthed a multi-billion-dollar industry, making the many middlemen who help facilitate each step of these transactions very rich.

This month, The Real Deal took a deep look at how the program’s key stakeholders — from developers to regional centers to banks to the so-called migration agents — are riding this EB-5 gravy train.

Detractors claim it favors projects in wealthy parts of the country, that it can be used to bring dirty money into the U.S. and that naïve Chinese investors sometimes get lured into investing in financially flawed projects. Proponents say EB-5 capital helps spur economic development.

TRD also looked at several New York City EB-5 projects that are teetering on the edge. Some of these projects are examples of how EB-5 is being used, and abused.

In some cases, developers have taken advantage of the loose guidelines to make projects seem like they are in low-income neighborhoods (known in EB-5 speak as Targeted Employment Areas). This type of gerrymandering allows developers to seek minimum investments of $500,000 rather than $1 million, giving them access to a wider pool of investors.

Many EB-5 projects are also slated to launch at a time when experts are warning of a possible market slowdown, which could put EB-5 investors’ money at risk. “The next big industry in EB-5 is litigation,” said Michael Gibson, managing director at USAdvisors.org, an EB-5 advisory firm.

Read on for a closer look at who’s profiting in the meantime.

How much longer will the EB-5 love affair last?