After years of sparring over its highest and best use, the fate of 5 World Trade Center was left to a competition.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the Lower Manhattan Development Corp. last year announced what was effectively a truce: The agencies would consider both residential and commercial visions for the site. Among them were Silverstein Properties and Brookfield Properties’ residential project and MaryAnne Gilmartin’s office tower.

But the world has changed since the September 2019 deadline for submissions.

“I think one of the most important things was what would provide the most revenue,” said Carl Weisbrod, a former head of City Planning who also served as a director of the LMDC. “In this climate, it could well be residential, but we’ll see.”

The dueling proposals capture the long-running debate about what a redeveloped World Trade Center complex should look like but now also reflect an existential question confronting New York and other alpha cities: Post-pandemic, can their central business districts survive?

That answer will depend not only on how individual assets are developed but also on how cities approach long-term planning and how the office market shakes out after an economic crisis and the shift to distributed work. The pandemic could transform building valuations, which would alter the entire real estate investment landscape.

The last few months have wrenched the discussion about land use out of academic salons and into action: New York and other local governments have adopted new pedestrian-friendly initiatives, for example, and liberalized outdoor dining rules.

“It’s mostly illustrating a lot of trends that were underway before the pandemic, which have all been accelerated by this,” said Ed McMahon, a senior fellow at the Urban Land Institute.

He said he believes the disruption will spark a new wave of investment and ideas. “I think this is all ultimately good for cities,” McMahon said. “Once those losses are written off, these properties will be riper for conversion to some newer and better use.”

He said he believes the disruption will spark a new wave of investment and ideas. “I think this is all ultimately good for cities,” McMahon said. “Once those losses are written off, these properties will be riper for conversion to some newer and better use.”

The zero-minute city

The pandemic forced governments to rethink how their citizens flow through public and private spaces. Individuals, confined to their homes, were confronted by the limitations of their immediate surroundings, as well as the lack of goods and services within their personal orbits. Many local governments were woefully unprepared, while others were already planning an overhaul.

In Paris, Mayor Anne Hidalgo had pledged in February to create a “15-minute” city as part of her re-election campaign. Coming a month before the city and much of the world shut down, it was a prescient promise.

Developed by Panthéon-Sorbonne University professor Carlos Moreno, the concept is simple yet provocative: Residents should be a short walk or bike ride away from most of their core needs.

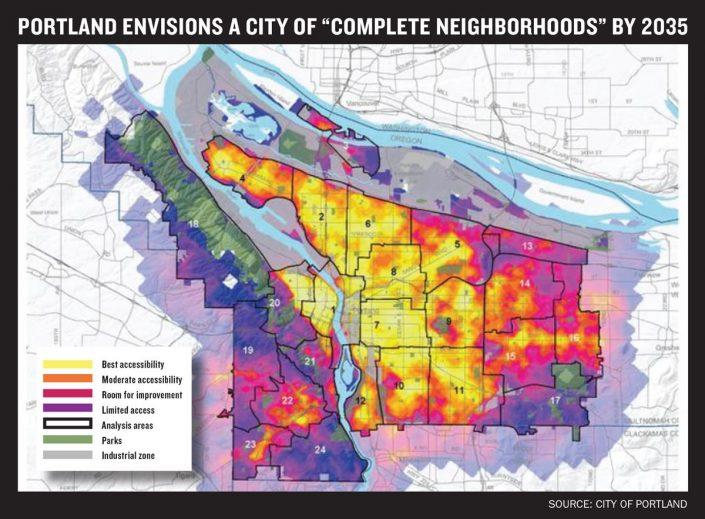

Other cities have adopted similar frameworks, including Portland, Oregon, which is moving forward with a plan to ensure that by 2035, 80 percent of its residents live in a “complete neighborhood” — meaning easy access to employment, grocery stores, municipal services and other needs.

Cindy McLaughlin, CEO of 3D mapping and zoning analysis startup Envelope City, said New York is well-positioned to embrace the concept.

“The idea is, if you had to, you would never have to leave your neighborhood,” she said.

That would require changing the makeup of New York City’s central business districts and creating more such hubs outside Manhattan.

Eldad Gothelf, director of zoning at Envelope City, said the city needs to loosen its rules around building conversions to allow for a wider range of uses in business districts such as Midtown East and Lower Manhattan.

It should also rezone areas designated for single-family homes to increase density in the outer boroughs, he said, following the lead of Portland and Minneapolis, which have effectively banned single-family zoning. Doing so could help change “the flow of the city,” which is Manhattan-centric.

“It maybe used to make sense, but it doesn’t anymore,” Gothelf said. “We need a redistribution of density throughout the city, a decentralization of central business districts.”

Weisbrod, who founded the Downtown Alliance, said that Lower Manhattan went from a commercial district that shut down after work to a thriving, mixed-use community. He expects residential neighborhoods to gradually move toward the same “live, work, play” model. Gilmartin declined to discuss 5 WTC but said the pandemic reinforced the idea that “New York needs a greater diversity of business districts outside of Manhattan.”

“People increasingly want to live near where they work, they want access to open space during the workday and they want manageable density that is convenient without feeling overcrowded,” she said.

Jesse Shapins, director of planning and delivery at Sidewalk Labs, said there will likely be pressure to develop buildings in ways that allow for a change of use down the road.

“The opportunity now exists for developers, in some ways, to be more resilient,” he said.

Significant hurdles still exist. Last month, the developers behind Brooklyn’s Industry City pulled a proposal for a rezoning that would have allowed for more retail, office and academic use, after it became clear that they were short on political buy-in. The rezoning’s demise, which New York business leaders considered a debacle, led industry insiders to question the city’s approval process.

At the height of the pandemic, people were in need of a diversity of uses built into their own homes, a concept called “zero-minute” cities, said Vicente Guallart, former chief architect for Barcelona. His firm drafted a proposal for a four-block project that incorporated wish list elements including rooftop farms, 3D printers (for making masks) and renewable energy sources.

Dubbed “Self-Sufficient City,” the project was part of a competition for a community in Xiong’an, a city just outside Beijing. Chinese President Xi Jinping reportedly called it “a new standard in the post-Covid era.” To turn it into reality would require governments to embrace taller-than-usual wooden construction — a central element of Guallart’s design.

“The history of humanity shows that there is always resistance to change,” he said. “I think the pandemic has accelerated the future.”

Temporary street closures and the reallocation of public space have sped up discussions about car-free design and helped break political logjams. Shapins pointed to Toronto, which in May approved the creation of 25 additional miles of bike lanes. That means 40 miles of bike lanes will be added this year, the most in the city’s history, according to the Toronto Star. In New York, architect Vishaan Chakrabarti’s vision for a private car-free Manhattan gained broad attention. (Chakrabarti said, however, that the reaction from the real estate industry was “crickets.”)

Public policy changes have largely been reactive to the immediate needs spawned by the coronavirus crisis, rather than big-picture thinking about the future. Architecture critic Alexandra Lange had hoped street closures for outdoor dining would inspire New York officials to carve out more public space for other community activities but said that hasn’t materialized.

“I don’t see it building,” she said. “I see this fixation on just a few uses, which is disappointing.”

We are not worthy

Long-term, cities will need to reexamine not just the use of space but also time — a phenomenon Lange calls the “choreography of waiting.”

The pandemic dramatically changed commuting patterns, and as people return to work, they won’t necessarily revert to their previous routines. Companies are considering staggering start times for employees and having workers reserve desk and conference space. The practice, known as “hoteling,” is already being implemented by some firms, including Starbucks at its Seattle headquarters. If widespread, it could shrink office footprints and have broader design implications for surrounding areas.

In the U.S., CBRE forecast 50 million square feet of negative net absorption for the second half of 2020 and the first annual decline in net absorption since 2009. A Savills survey released this month of 250 technology companies found 82 percent of them anticipate needing less office space over the next 12 to 18 months.

As lockdowns eased over the summer and the real estate industry began figuring out how to get going again, two of the country’s largest office owners put trophy assets up for sale in what was seen as the first big test of the Covid-era market.

SL Green Realty listed its Amazon-anchored office building near Hudson Yards eyeing a price tag of $1.1 billion. And Vornado Realty Trust shopped a 70 percent stake in two trophy office towers in Manhattan and San Francisco that it co-owns with the Trump Organization.

Investment-sales insiders said that SL Green’s building, at 410 Tenth Avenue, is generating strong interest thanks mostly to the strong credit rating of Amazon, whose stock has skyrocketed during the pandemic.

Vornado’s offerings, by contrast, have struggled, sources said, because of challenges exacerbated by the pandemic at the two properties: A big chunk of the leases at 1290 Sixth Avenue are rolling over in the near term, and it could be hard to fetch top-dollar rents at a building many consider dated.

Meanwhile, Vornado’s San Francisco building at 555 California Street, which insiders told Bloomberg could be worth $2 billion, is in an area where officials want to permanently mandate 60 percent work from home.

The confusion surrounding valuations isn’t limited to office space. Owners of a variety of building types, from multifamily to hotels to retail, are struggling to understand what their properties are now worth.

“In certain locations, because of the lack of transparency, it’s very difficult,” said Bob Knakal, chair of New York investment sales at JLL. “The art of investing is figuring out what [investors] can afford to pay and how they’re underwriting different scenarios.”

High-street retail in urban cores was already in the dumps before the pandemic. Hotels still have little idea when business and tourism travel will resume. Earlier this month, Pakistan International Airlines announced it was shutting down its 1,015-key Roosevelt Hotel, following in the footsteps of the W Hotel in downtown Manhattan, the Hilton in Times Square, the Courtyard by Marriott in Herald Square and the Omni Berkshire Place hotel.

Near-zero hotel sales means few comps to gauge pricing, though investors do have some data to look to: Many hotel properties that have had their securitized loans transferred to special servicing received new appraisals. On average, they are coming 29 percent lower than their pre-pandemic figures, according to Trepp.

While appraisals don’t always match up with market pricing, they serve as a benchmark for investors desperate for information.

“In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king,” said Manus Clancy, who heads Trepp’s applied data and pricing division.

Down the road, the pandemic could have a much broader impact on valuations. The biggest factor for city centers, many believe, is whether it will create or reduce demand for office space and how that space will be distributed.

On top of that, valuations could be changed by legal rulings on force majeure clauses in leases and whether pandemic-related losses are covered by business interruption insurance. The outcomes could have significant ramifications on properties’ profit and loss statements, similar to the way the 9/11 attacks created a new expense: terrorism insurance. That might have been prohibitively expensive had the government not decided to backstop it — which property owners are reminded of every few years when the federal Terrorism Risk Insurance Act comes up for renewal.

And exactly what insurance companies are liable for in a terror attack only became clear after World Trade Center owner Larry Silverstein sued.

“That was one state and one jurisdiction,” Clancy said, noting that the pandemic will be testing interpretations on things like force majeure across the country. “Now you’ve got 50 states and 50 judges all looking at it differently.”

Valuations will also depend on the size and shape of the economic rebound. Some predict the comeback will be K-shaped, where some companies do resoundingly well and others are decimated. The divide between buildings with tech or life-science tenants and those filled with tenants from struggling sectors such as retail could get even wider.

If the pandemic dilutes values for certain properties, it could end up making cities more affordable and stem the migration being seen from cities such as New York and San Francisco.

At the end of June, Deloitte released responses from a survey of more than 27,000 millennials and Gen Zers and found that 56 percent said if given the opportunity to work from home, they would live outside of major cities in places with lower costs of living.

“Longer-term, in some ways this could be good for cities,” ULI’s McMahon said.

Clarity about how to approach development and land use, however, will only come with time.

“Spending too much money in one direction is really foolhardy,” said Lange, the architecture critic. “We don’t understand the full contours of the virus to make these physical design decisions.”