This decade has been good for multifamily development. From Port Chester to Eastchester to Cortlandt Manor, Westchester County has been adding rental units at a brisk clip after years when those types of projects comparatively dribbled onto the market, according to an analysis by The Real Deal.

It’s no longer a new phenomenon, and in fact, the number of added units from 2011 to date peaked in 2016, according to TRD’s data. In 2017, there were slightly fewer units added, and some say the suburban market may be oversaturated, though it’s worth noting that these developments have been much rarer along the Hudson River, where officials have been reluctant to approve them. Multifamily lending is slowing down (see our story on page 22), and there’s a renewed interest in single-family homes here.

But brokers in the area are adamant that there’s still room for growth, saying that these developments cater to a certain type of tenant, often renters who want easy access to Manhattan but also a lively local nightlife. “People want to live in areas where they can walk to stuff,” said Joseph Rand, a managing partner of Better Homes and Gardens Rand Realty, which is active in Westchester. He sees the increased-density areas as still very much in demand — at least for the next few years.

Several multifamily projects have come to fruition in 2017, with some brokers planning on adding more of this type of product to their listings in 2018.

By the numbers

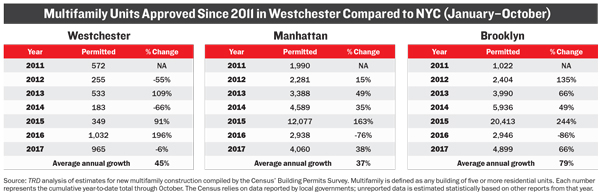

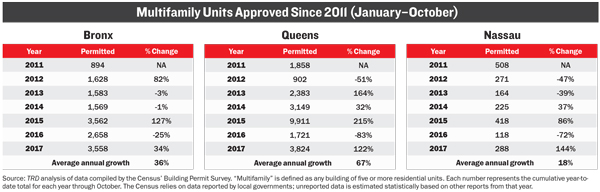

TRD’s analysis, which considered a multifamily building to be one with five or more units, relied on building permit counts supplied by local governments to the U.S. Census, as well as estimates from other housing reports. The analysis, which studied the period from 2011 to the present using only the months January through October for consistency with the available 2017 data, didn’t distinguish between market-rate, affordable and senior housing.

Between January and October 2016, 1,032 multifamily units were approved for construction in Westchester, which represented a nearly 200 percent increase over 2015, when 349 units were approved. That 2016 total was nearly equal to the previous three years combined, according to TRD’s data.

And in 2017, in the same period, 965 units were approved in Westchester, a number that’s close to that 2016 high point. The recent nadir was 2014, when just 183 units were approved across the county, according to the analysis.

Those totals, of course, seem meager compared with large urban areas. To wit: From January to October 2017 in Manhattan, 4,060 units were green-lighted, TRD’s reporting showed, while Brooklyn was even more saturated, with permits approved for 4,899 multifamily units.

Yet Westchester still seems to be leaps and bounds ahead of similar suburbs, like Nassau County, Long Island, which in the same 10-month span saw only 288 multifamily permits, according to the data.

“First and foremost, there is a demand for housing here,” said Whitney Okun, a marketing director with Houlihan Lawrence. “And there is an immense amount of housing in the pipeline.”

In January, Houlihan Lawrence will begin marketing three major luxury rental projects, she said. All of them are transit-oriented, even if not always adjacent to the railroad tracks.

They include Elm, in Elmsford, a 100-unit project next to the Saw Mill River Parkway with studios to two-bedrooms from Robert Martin Company, a developer that is headquartered nearby. Studios will start at about $2,000 a month, Okun said.

Elm, in Elmsford, is a 100-unit project next to the Saw Mill River Parkway. Studios start at about $2,000 a month.

There’s also Glasshouse250 in Hartsdale, which has a stop on Metro-North Railroad’s Harlem line. Developed by the Ted Weinberg Building Company, the 50-unit complex offers one- and two-bedrooms, with rents starting at $2,500, according to Okun. Most are priced at market rates, but there are some affordable units, she added.

Houlihan Lawrence is also offering Phillips Harbor in Mamaroneck, a seven-townhouse project from Michael Rosen. Though it’s been on a much smaller scale, there’s also been condo activity in the area. Interest in them is coming from empty nesters, Okun said, noting: “Not everybody is willing to make the big leap to the city.”

Okun said another local marketable factor is the quality of nightlife, including the renewed restaurant scene in Port Chester. “I don’t feel the need to go to the city as much, because I can go and experience different kinds of cuisine,” said Okun, who relocated to Westchester from New York City four years ago.

Post Chester recently welcomed the Light House, a 50-unit rental building developed by David Mann, with studios to two-bedrooms. Studios start at $1,950 a month, said Julian Diaz, a salesman with Better Homes, which is leasing it. It launched rentals last winter and is now fully occupied, Diaz said.

Back to the future

During the last real estate boom, luxury-condo fever gripped some Westchester communities. Examples stand in White Plains and New Rochelle, including a pair of Trump-branded high-rises, though the towers in many ways never triggered the development wave some predicted.

Any shortfall, however, can be largely blamed on the recession. In fact, in many ways the current surge in some of Westchester’s cities represents a return to normal.

New Rochelle, for one, is now awash in residential projects, most led by RXR Realty, which has development rights across the city (see page 16). One will add two 28-story towers with up to 700 apartments. Separately, a team led by RXR is at work on a 28-story, 280-unit rental tower nearby that also will offer a theater.

Those cities, as well as Yonkers, are also enjoying a bit of a revival after years when they were troubled by crime and blight. Still, multifamily development has been a touchy subject in Westchester. Zoning rules that have limited apartment buildings have been blamed for segregating communities in violation of the federal Fair Housing Act.

In 2007, the Anti-Discrimination Center of Metro New York, an advocacy group, sued the county over the zoning, saying it produced all-white communities in some cases. The suit also said that the county was wrong to accept $45 million in funds to create affordable housing because it did not fulfill its end of the bargain.

Though the suit was settled in 2009, with the county agreeing to build 750 affordable units in 31 white-majority communities, little progress was made, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development. For years after the settlement, the agency insisted the county was still in the wrong, because affordable units were ending up in neighborhoods that were already integrated.

This past summer, about a month into the tenure of Lynne Patton, HUD’s new regional administrator, the department changed course. It approved Westchester’s plan, saying the county had finally complied with the 2009 decision. (Read TRD’s interview with Patton on page 42.)

The county was supposed to oversee the creation of 750 units, not all of which were in apartment buildings, according to county housing officials. The total actually exceeded 750, they said, but that’s still a small percentage of the 4,000 or so apartments approved in the last six years.

In other communities, condos are just arriving. Bronxville now features VillaBXV, a 53-unit Mediterranean-style complex that opened in October near a Metro-North stop. Plans for the project, on the site of a former power company, began before the last downturn.

Bronxville, an affluent village that’s part of the town of Eastchester, had zero multifamily units approved between 2000 and 2016, according to the data.

National developers are also flocking to the region, like Toll Brothers Apartment Living, a division of the company known for its single-family houses. It’s at work on a 421-unit rental complex called Carraway in Harrison.

Being constructed on the site of a former office building, the apartment house, which mostly has one-bedrooms, is supposed to open by 2020, said John Piedrahita, a Toll Brothers marketing director.

Another project in that town, Wood Works, also from David Mann, has 36 rental apartments and is 60 percent occupied since September, when leasing began, said Diaz of Better Homes.

A mixed picture

Ground has also been broken in villages and towns that had little to show in the way of new multifamily housing for years, including Somers and Elmsford. Since 2011, those communities have added about 10 percent of the county’s total new units after not adding a single unit from 2000 to 2009, the data shows.

All has not been rosy, however. Places like the town of Yorktown, at the northern edge of the county and not directly served by commuter trains, were enjoying heavy multifamily activity prior to the housing crash but have largely sputtered out since then. Just 12 units have been permitted since 2011, according to the data.

And there seem to be communities, despite their compact blocks and public transportation options, where multifamily development continues to be rare.

The river towns, including the village of Irvington, have not permitted a single unit in a five-unit structure since 2000. In the village of Dobbs Ferry, there have been just eight in the same time span, according to TRD’s analysis.

It’s also the case inland. The town of Scarsdale and the village of Scarsdale also have not permitted a single multifamily unit since 2000, according to the data.

Critics say the millennial market is shallower than people think, adding that multifamily developers in Westchester are getting too far ahead of themselves. One reason cited: Millennials often prefer to live in big cities, if they can. Many would rather pay more than give up conveniences and move to the suburbs, where amenities can be scarcer.

But some Westchester brokers aren’t buying that line.

“The market incline is really good; the three- to five-year window looks really promising,” Rand of Better Homes said. “And the denser you can build, the better.”