The following is an excerpt from The Real Deal‘s upcoming book on New York’s new era of skyline shapers, the men and women who were at the center of the city’s rise from the depths of 9/11 to its position today as the world’s financial and cultural center and playground for the global superrich.

It includes previously untold perspectives from the city’s biggest moguls on how they built, seized and lost their fortunes — and then did it all over again, at skyscraper scale.

On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, Kent Swig was rushing to an appointment at 2 World Trade Center with his bankers at Lehman Brothers. Swig had a busy day ahead. It was his son’s eighth birthday, and the family was heading to a magic show that evening. The New York City mayoral primaries were also happening, and Swig meant to vote before work but had gone to the wrong polling place.

Now, as he scrambled down the stairs to the subway on that cloudless day, he feared he might be late for his meeting. It was only when he entered the station and headed toward the 4 train platform that someone informed him that a plane had hit one of the World Trade Center towers and “all hell had broken loose Downtown.”

There would, of course, be no meeting between Swig and his lenders that day.

Thousands were dead in the rubble of the World Trade Center. The U.S. was at war. And nothing Downtown would ever be the same.

In the weeks that followed, some developers would be thrown into the spotlight in ways they never imagined.

Larry “Energizer Bunny” Silverstein had gotten his start as a broker in the Garment District in the 1950s and built a portfolio with his father and his then-brother-in-law, Bernie Mendik. He had taken over control of the WTC site just six weeks earlier, after an extended bidding war with Vornado, Brookfield and Boston Properties. Silverstein’s $3.2 billion deal to secure the ground lease to the 11 million-square-foot complex was the biggest transaction in New York history. It had catapulted him to the top of the developer pecking order.

“I’m thrilled to pieces,’’ he told the New York Times after the deal was announced. “I’ve been looking at the Trade Center for years, thinking, ‘What a great piece of real estate, what a thrill it would be to own it.’ There’s nothing like it in the world.’’

Now he had become one of the key faces of the disaster. His precious new buildings had been reduced to rubble. The land he had fought so hard to gain control over had become a graveyard. Silverstein, like everyone else, was in a state of shock. But he was also a pragmatist.

“I ran into him — he was about to go into a place to have dinner, and I ran into him on the street on the Upper East Side,” Mary Ann Tighe, the city’s top office leasing broker and a key player in the post 9/11 rehabilitation of Downtown, recalled to The Real Deal about Silverstein. “We were standing in front of each other and I began to cry. And he put his arms around me and said, ‘Sweetheart, gonna rebuild.’ This is 6 o’clock on the night of 9/11.”

Silverstein said the attacks gave him a sense of single-mindedness.

“It’s funny, but I don’t recall the focus [of my thoughts at that time], other than the disaster, and the magnitude of the problems we were facing as a result of it,” he said in an interview with TRD in 2011.

For many of the other Downtown landlords who would eventually come to be associated with the city’s recovery, the sheer magnitude of the disaster that day blotted out any thoughts of business. It seemed almost as if the world were ending.

Steve Witkoff was in his office at the old Daily News building up on 42nd Street, and could see the smoke coming from the towers through his windows. At 9:59 am, he watched in horror as the South Tower came crashing down, followed 29 minutes later by its twin next door.

Witkoff rushed up to the Bronx to collect his children from the Riverdale School. Soon after returning home, he got a call from Bo Dietl and Mike Ciravolo, two old friends who were retired NYPD detectives. They suggested heading Downtown to help, which is how Witkoff ended up standing on a piece of mangled steel, on a rope line until 5 a.m. the next morning, holding the end of a long cord tied around the belly of a firefighter with a flesh-sniffing dog digging through the rubble of the massive pile of debris, searching for survivors.

Witkoff had seen New Yorkers go through hardship before. But what he would see in the days following 9/11 was well beyond anything he had experienced.

Born in the Bronx and raised on Long Island, Witkoff had started out in the late 1970s as an attorney at Dreyer & Traub straight out of Hofstra Law School. As a young associate, he pulled 90-hour weeks working on real estate deals. But, like Steve Ross, he had longed to get in the game himself.

“Every day you were representing these swashbuckling guys who were entrepreneurial in their spirits,” Witkoff said of his clients, such as Peter Kalikow, Arthur Cohen and Howard Lorber. “They felt like rock stars to me.”

Witkoff made his first property buy in 1986 at 29, borrowing $15,000 from his father and partnering with his Dreyer colleague Larry Gluck on a $240,000 building in Washington Heights. They financed it just like some of the deals they had worked on for clients, getting a loan backed by the government-sponsored Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, Freddie Mac. Witkoff and Gluck soon left the law firm behind and set up shop as Stellar Management — the name being a combination of Steve and Larry — in a 150-square-foot office on Park Place.

By the time the market began to turn down in 1989, Witkoff and Gluck owned 10 properties Uptown. Unable to unload them — they had originally intended to be “deal guys” — they realized they would have to learn the ins and outs of real estate, including how to deal with frozen pipes and work with Albanian supers to save money on repairs.

Washington Heights at the time was still plagued by drug dealing, gangs and violence, and Witkoff, chatty by nature, grew close to many of his tenants, hearing firsthand about tragic deaths and the scramble to make ends meet. He recalled one young mother he was friendly with inviting him up to her apartment for sex because she needed money to buy food for her children (he gave her the money and declined the sex). He discovered another family living illegally in the basement because they couldn’t afford rent. (Witkoff moved them into an apartment.)

He learned to use a gun, and began carrying one Uptown in his gym bag. He spent New Year’s Eve in 1991 in the basement of a building on 124th Street and Madison Avenue, helping his plumber with a sewage backup. For years, he kept a copy of the book “Tough Jews,” a romanticized account of Jewish gangsters, on his desk.

Witkoff and Gluck made their Downtown debut in 1994. They realized they could buy a foreclosed office building around the corner from their headquarters for $4 million, less than $20 a square foot, and by relocating there save money on rent. Witkoff split from Gluck in 1997, and by 2001 he was a major player in the area. He had as many as 10 buildings there, including the magnificent Woolworth Building, a 60-story, terracotta-clad tower that was once the world’s tallest skyscraper.

Now, several of his properties were smack in the middle of what now looked like a war zone.

After that exhausting night on the pile, Witkoff walked into the ornate lobby of his $146 million trophy, with its cathedral-like ceilings, bronze fixtures and elaborate glass mosaics, and was surprised to find exhausted firefighters, police officers and other first responders stretched out on virtually every inch of available floor space. Their clothes were covered in ash, and their hands were raw from digging through the rubble, he recalled, which made for a shocking tableau set against the marble floors and rich red carpeting of the tower.

Witkoff was so moved, he walked an American flag up to the top of the skyscraper — the elevators were out — and raised it. He moved a generator in, vowing to keep the building open no matter what. For the next 30 days, the building served as a staging area, and slept much of the 10th Precinct and first responders from other areas.

As the scope of the tragedy became clear — Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaida terrorists had killed nearly 3,000 people, traumatized the city and pushed the U.S. to go to war — Witkoff began attending funerals and doing all he could to help out. He made a conscious effort to block out thoughts of what the tragedy might do to his empire.

He had purchased almost all of his buildings at an extremely low-cost basis, and most of his tenants were on long-term leases. When President George W. Bush visited the site on Sept. 14, slung his arm around a firefighter and addressed first responders through a bullhorn, the Woolworth Building looming in the background, Witkoff was standing a few feet away, a guest of Police Commissioner Bernie Kerik.

“I decided it was beneath me to worry about my business,” Witkoff said. “I remember thinking this can’t be about business. And I was deeply inspired. It was, ‘What can I do?’ Guys who had uniforms on are walking up these staircases to rescue people, and they all died. They didn’t go home to their families. That’s when I remember thinking: ‘I cannot do enough.’”

When the city did begin to take stock of the damage, however, the devastating destruction of property loomed among the most obvious, and expensive, consequences. Downtown had lost 15 million square feet of space, with nearly 13 million square feet destroyed and over 2 million square feet declared structurally unsound as a result of fires, falling debris and building collapses.

An additional 11 million square feet were damaged, and roughly half would be taken off the market for at least a year. The World Trade Center/World Financial Center submarket totaled 40 million square feet, according to JLL — and half of that had been taken out by the attacks.

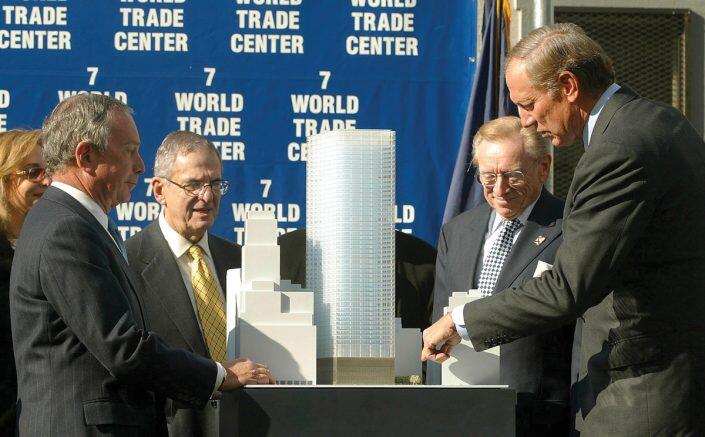

From left: Mayor Mike Bloomberg, publicist Howard Rubenstein, Larry Silverstein, and New York Governor George Pataki look at the unveiled plan for the rebuilding of 7 World Trade Center in November 2002 (Getty Images)

Downtown’s future was unclear. A toxic cloud would hang in the air for months. Tenants in search of new space looked elsewhere. The overall area office vacancy rate, 6.2 percent in August 2001, would spike to 15.6 percent in the weeks that followed.

The psychic shock of those two huge towers coming down also caused people to rethink what was possible. Around the city — around the world — some even began to question whether there was a future for skyscrapers at all.

Gene Kohn, founder and chair of architecture firm Kohn Pedersen Fox, predicted to Scientific American that there could be a hiatus in skyscraper construction “lasting as long as a decade.”

Related had launched sales at the Time Warner Center just a month before 9/11. William Mack, Related’s equity partner on the project, received an early indication of what the attacks might do to their marketing efforts. One of his tenants threatened to pull out of another building Mack owned — in Pittsburgh.

At 64 stories, the USX Tower was the tallest skyscraper in the city. Prior to the attack, Heinz had been on the verge of signing a 15-year lease to occupy the top three floors. Now, the food-processing giant balked. What, they asked Mack, if terrorists took down their building next?

“That’s when I said, ‘Who’s going to Pittsburgh?’” Mack recalled.

Mack’s reassurances were not enough. Heinz went elsewhere.

“It’s hard to put yourself in the position of people then. There was a great fear that anything that was a high-rise they’d be banging planes into, and the security couldn’t be accommodated,” he recalled.

Looking back years later, Related’s Ross would downplay his own fears, claiming that by then he knew it would pass.

“Of course it was stressful,” Ross said. “You’re reading articles in the paper, and you’re thinking, ‘Would there ever be another high-rise in New York?’ You know, you’re wondering what’s going on in the world. You react to it. But you don’t crumble.”

Ross and Mack still had 163 condos left to sell at Time Warner. And company executives admitted that a number of buyers had asked for time to reconsider. One friend of Mack’s, who had intended to buy, informed him his wife refused to live above the 15th floor. He was not the only buyer they lost.

Slowly, however, the city’s housing market began showing its resilience.

In November, Related announced that more than $45 million in condo contracts had been signed since the attacks, bringing the total to $105 million. A crawl compared to what had been expected before the attacks, but a positive sign nonetheless.

The condo market’s brashest cheerleader was also back at it. In late November, a group led by Donald Trump beat out three other bidders with a contract to pony up $115 million for the 169-room Hotel Delmonico, a storied Upper East Side property on 59th Street and Park Avenue. Built in 1928, the property was converted into apartments by William Zeckendorf Jr. in 1975, then converted back into a hotel by different owners in 1991 (Zeckendorf still used the penthouse as a pied-à-terre).

Trump’s deal, the Times’ Charles Bagli wrote, was a sign that “the real estate market has not collapsed.” Trump, Bagli noted, was planning on transforming the Delmonico into a condo-hotel, “not unlike” the Trump International Hotel and Tower across town at Columbus Circle. Trump would eventually name the development, perhaps predictably, Trump Park Avenue.

Weeks after 9/11, Michael Bloomberg, founder of financial-services firm Bloomberg LP, was elected the 108th mayor of New York City. The ascension of a multibillionaire technocrat to the top job was to have a profound impact on the direction the real estate market would take.

Short, slight, with thin lips and a receding white hairline and always fastidious in his dress, the new mayor could come off as robotic or wooden. Yet in the months following the greatest tragedy in New York history, there was something profoundly comforting about Bloomberg’s unflappability.

A long-shot candidate prior to the attacks, Bloomberg pumped $73 million of his own money into his campaign, outspending his opponent five to one. He argued that New York needed a seasoned business executive to rebuild, and voters bought into that argument. One of his first tasks would be coming up with a plan for devastated Lower Manhattan.

Bloomberg’s predecessor, Rudy Giuliani, and New York Gov. George Pataki had announced plans to create the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation to oversee the reconstruction of the World Trade Center site.

Two months later, in February, the City Council approved a zoning permit for the first new project in Lower Manhattan since the attacks. The permit went to the residential developer Glenwood Management and its grizzled octogenarian chair, Leonard Litwin. Glenwood planned to construct a 45-story residential tower, with 288 apartments, office space and ground-floor retail on Liberty, William and Cedar streets. The industry had planted a flag in Downtown.

In December 2002, Bloomberg strode into the ballroom in Wall Street’s Regent Hotel, a stately Greek Revival landmark that once housed the New York Stock Exchange.

Taking his place at the front of a rotunda, he addressed the city’s business leaders, unveiling his vision for the future of Downtown in a breakfast speech before the Association for a Better New York.

The “ailing” financial center that largely shut down at night would be transformed into a collection of neighborhoods — a vibrant 24-7 “urban hamlet” with housing, schools, libraries, and movie theaters, he said. West Street would morph from a six-lane highway into “a promenade lined with 700 trees, a Champs-Élysées … for Lower Manhattan.”

Bloomberg told the business elite he would create a larger Battery Park, and entirely new parks over the mouth of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, stretching from the Battery Maritime Building to the South Street Seaport. There could be baseball fields, an outdoor skating rink and floating gardens.

He envisioned 10,000 new apartments south of Chambers Street in two new neighborhoods, one near Fulton Street, and a second south of Liberty built around a new park. He also called for tax breaks to attract foreign companies and direct transportation links to the nearby airports.

“We have underinvested in Lower Manhattan for decades,” Bloomberg said. “The time has come to put an end to that, to restore Lower Manhattan to its rightful place as a global center of innovation and make it a Downtown for the 21st century.”

The plan had a $10.6 billion price tag. But with $21 billion on the way from the federal government, 9/11-related insurance money and newly authorized “Liberty Bonds” for new housing Downtown, it was not fanciful.

“Moving forward,” Bloomberg declared, “Lower Manhattan must become an even more vibrant global hub of culture and commerce, a live-and-work-and-visit community for the world. It is our future. It is the world’s second home.”

Covering the speech, the Times noted that Bloomberg had devoted only 20 seconds of its 31 minutes to the WTC site.

He didn’t need to. That came on Dec. 18 in a widely covered event in the Winter Garden, the glass, tree-lined, indoor atrium on the edge of the Ground Zero site, when some of the world’s top architects presented their visions for the site. Daniel Libeskind’s proposal to build five skyscrapers on, including a modern crystalline centerpiece with a towering spire that would be called Freedom Tower, would be selected as the winner in February 2003. The footprints for the original towers would be transformed into a memorial.

When the planes hit, Kent Swig had just completed the renovation of his Bank of New York Building and had been preparing to go on a major buying spree. After the attacks, he decided to wait and see how things unfolded.

He had made one significant real estate play, however. In 2002, Swig and his wife, Liz, had demonstrated they possessed the requisite $100 million in liquid assets and moved, with their two young sons, into a 16-room, five-and-a-half-bath duplex at 740 Park Avenue, the city’s most prestigious co-op.

Every morning on the way out to work, Swig would nod hello to moguls like Ronald Lauder, Steve Schwarzman and David Koch. Liz decorated the Upper East Side apartment with “funky art and color-coordinated candy,” according to a press report. She was featured in a 2003 New York Magazine article exploring how to have a successful dinner party, right alongside Diane von Furstenberg, Tina Brown and Joan Rivers.

To celebrate her brother Billy Macklowe’s birthday, Liz had several hundred pounds of slate, wildflowers and climbing accessories shipped in, and served trout wrapped in foil. The menu was superimposed over a photograph of a shirtless Billy, a noted outdoorsman, dangling from a cliff. Swig and Liz spent their weekends at a 4-acre waterfront estate in Southampton and took surfing trips to Australia.

By the summer of 2003, Swig was done waiting. He had concluded he might just be looking at a transformational opportunity.

He announced that 48 Wall was 96 percent leased and that he had refinanced the $55 million loan on the property.

Swig commissioned a study that found that in 2000, more than 34 buildings in Lower Manhattan, representing almost 13 million square feet, had been converted to residential, creating an even more profound shortage of high-quality office space in smaller buildings. If he could replicate what he had done at 48 Wall, there was plenty of demand.

Swig was still perplexed by the price differential between Midtown and Downtown — a gulf that, after 9/11, had grown even more vast.

“I looked at a massive tragedy and said, ‘I’m down in this area, what the hell is going on?’ I looked at my business plan and said, ‘Does it make sense? Yes.’ Perception has gone even further down, and nothing has changed.”

That summer, Swig bet on his gut, paying $52 million for 5 Hanover Square, a 25-story office tower built in 1962. He announced plans to convert it into a “luxury boutique-style office complex,” with better bathrooms, new elevators, floors of Italian travertine marble and an all-glass façade. Within a few weeks, the building had picked up several new tenants and was 98 percent leased.

In November, Swig and partner David Burris teamed up with Iranian émigré and diamond mogul Asher Zamir to buy 44 Wall Street, a gem built in 1927, for less than $200 a square foot.

He kept going, buying the 36-story 80 Broad Street and another 25-story building next door. He snapped up 110 and 130 William Street. These were the go-go, subprime, pre-bubble days, with low interest rates and readily available credit. Swig, readily backed by Lehman Brothers, had his fill, and then some. By the time he was all done — by the time Swig instructed his assistants to throw out any incoming offering sheets because he didn’t want the temptation — he had a portfolio that exceeded $3 billion.

“I went and bought everything I could,” he recalled. “I started in 2003, and bought until January 2006. I bought every single property I could possibly buy. I was buying buildings all under $198 a foot. Never paid more than $198. Land was trading at that time probably for $250 a foot. So either I bought the land cheap and got a free building, or I bought a building and got free land, but nobody was doing it. Everybody was looking at me like I’m a fool.”

“The market was mine,” he added. “Nobody was doing this. Everything that moved, I bought. Literally bought every building. If it came up, in three days, I bought the building. When brokers came to me, and said, ‘Here are eight buildings, 3 million feet. Pick wherever you want,’ I’d say, ‘I’ll have all of it.’