The real estate crowdfunding platform Fundrise recently posted an unusual offering on its website. The opportunity involved a chance to invest in a residential property “located in Mars’ up-and-coming Red Hill Neighborhood.”

Fundrise’s website extolled the benefits of that “Mars Colony Offering,” promising infinite returns for a minimum investment of $1,000.

While the offering was, in fact, an elaborate April Fools’ Day joke, it captured the sense of possibility that’s gripped the real estate tech scene.

In the last three years, the real estate world has seen a veritable boom in the number of tech start-ups. And while many of those firms have made headlines for their splashy entrées onto the real estate scene, some are clearly pulling ahead as others are trailing.

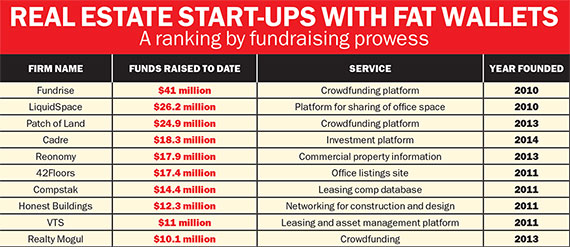

This month, The Real Deal ranked those start-ups based on how much venture capital they’ve raised. The data — gathered from CRE/Tech Intersect and Crunchbase, which both track start-ups — includes companies based in New York City as well as those that do business here.

TRD focused on firms that are using novel technologies to change the way the industry operates. So while start-ups like the office-sharing firm WeWork and the residential brokerage Compass, which have raised $362 million and $73 million respectively, have competed for venture capital dollars, they were excluded because they’re not primarily tech companies.

Instead, crowdfunding sites and websites aimed at the commercial sector dominated the ranking.

Fundrise took the top spot with $41 million raised since it launched in 2010. It was followed by shared-office search platform LiquidSpace, which raised $26.2 million, and California-based Patch of Land, another crowdfunder, which raised $24.9 million.

Cadre, a real estate investment platform backed by Jared and Joshua Kushner, ranked fourth with $18.3 million raised, while Reonomy, which offers detailed information on commercial properties, rounded out the top five with $17.9 million raised.

Some well-known tech start-ups like New York-based crowdfunding firm Prodigy Network didn’t make the list because they haven’t raised significant venture capital in the U.S.

While the real estate industry has long been known for its resistance to technological innovation, these firms are looking to fundamentally transform the way the industry operates — from the way real estate players access information to the way properties are bought and sold. And they are all harboring hopes of becoming the next billion-dollar company.

But as the number of start-ups has exploded, so has the sense that many of them will fail.

“There is only a finite number of firms that can be profitable,” said Sam Chandan, head of Manhattan-based Chandan Economics. The question currently preoccupying the real estate industry is: which firms will survive?

Finding the void

For all new companies — whether they’re making pickles or selling financial products — the key to success is usually finding a void in the marketplace. According to TRD’s ranking, that also holds true with real estate tech firms.

Companies that focus on finance and on providing information to the commercial community have raised the most start-up money, while residential-focused start-ups are noticeably absent from the list.

The explanation, according to insiders, is that commercial real estate has been starved of technological innovation, leaving a huge hole for start-ups to fill.

“Commercial real estate is one of the largest markets in the world, and it has been behind the curve” in terms of technological innovation, said Jordan Bettman, a senior principal at Bain Capital Ventures, a venture capital firm that’s invested a number of tech start-ups, including Reonomy.

On the residential side, the barrier for entry is higher, sources said. That’s because websites like Zillow and Trulia, which are now part of the same company, already cornered the market for online residential listings information.

Of course, while venture capital funding is an important marker of success, it’s not a perfect measure. The amount of money a firm raises can be seen as a measure of its potential, but since accepting venture capital usually requires giving up an ownership stake, start-ups generally don’t raise more than they need. In other words, a promising start-up may not rank well if its operating expenses (and investment needs) are low.

Also, since none of the latest New York–focused real estate tech start-ups have gone public, their earnings aren’t publicly accessible.

In addition, there’s no good way to judge an idea because, as many sources pointed out, the business world is full of brilliant innovations that failed to make their inventors rich. “Some ideas are going to be great but end up proving to be unprofitable,” Chandan explained. Or worse: they may end up being profitable for someone else.

For example, a little-known South Korean firm, Saehan, is credited with introducing the first portable MP3 player in 1998. Although it sold 50,000 players that year, Saehan soon fell behind its competitors. Apple’s iPod, in particular, became a multi-billion-dollar business, while Saehan shuttered its MP3-player sales division in 2003.

Occupational hazards

Launching a start-up comes with some substantial baked-in risks.

Veteran firms, for example, are often not shy about adopting a new company’s idea and using their size to quash anyone threatening their market share.

On the commercial front, established firms have already adopted ideas first pursued by start-ups.

For example, the real estate investment-banking firm Carlton Group and the Manhattan-based finance firm RCS Capital launched its own crowdfunding platforms last year.

“This was a great time to enter the space and, frankly, to add some structure to something that doesn’t have the typical boundaries our industry is used to,” RCS Capital’s president Michael Weil said at the time.

Another risk is that several start-ups attempting to corner the same space in the market could end up cannibalizing each other, sources said.

VTS and Hightower — which have raised $11 million and $8.7 million respectively — each offer cloud-based portfolio management, while a plethora of crowdfunding firms are vying for the same subset of investors.

“What we observe is that you will get multiple firms that will contest a certain space,” said Chandan.

So how can start-ups ensure that their ideas will pay off? The short answer is, they can’t.

But early and fast growth, sources said, can be a major boost. That’s especially true for listing sites and crowdsourcing platforms, which are subject to what economists call a “network effect,” meaning that the more people use them, the more valuable they become.

The New York–based CompStak, which crowd sources leasing comps, is a case in point. Since launching in 2011, the platform, which requires users to upload information about their own properties in order to get access to the rest of the database, has become a go-to source for leasing information. Its growing popularity and user involvement has, analysts say, created a buffer against potential competitors. If another company attempts to cut into CompStak’s space, it will have to convince users to abandon a platform they have grown accustomed to. “We have a strong competitive advantage by being the first [to offer crowdsourced comps], because we are a marketplace-type business,” said CompStak’s CEO Michael Mandel. “Every day it becomes harder for another company to come in.” Mandel added that securing this first-mover advantage is a main reason why the firm has already expanded into 15 U.S. markets.

The race for cash

For most start-ups, growing cash reserves is also key. This is where venture funding comes into play.

The ability to invest cash back into the business and to use it to lure top talent has increasingly helped distinguish tech start-ups. The nearly $18 million that Reonomy raised, for example, allowed it to hire Shutterstock’s Chris Fischer, a top technology executive, to head up its engineering efforts (see related story, page 142.) Meanwhile, with the help of its $11 million in venture capital, VTS has more than tripled its number of employees in the past year, to 65.

“We now have an 18-person team whose only job is to make sure our customers are happy. This is a massive competitive advantage for us,” said VTS co-founder Nick Romito.

The advantages of raising cash quickly are most apparent in the crowdfunding field, sources said.

Crowdfunding firms provide loans or equity to developers and real estate investors — often with terms as short as a year — which they finance with money from small-time investors. Potential borrowers about to close on a property often need money instantly, but raising money from hundreds of everyday investors can take days or weeks.

To solve that problem, some platforms have started pre-funding deals by guaranteeing loans and then assuming the risks of finding enough investors to cover them. But pre-funding requires significant cash reserves to bridge the time between the loan closing and the time the capital is fully raised from investors.

That’s the main reason why Patch of Land and Fundrise are raising substantial amounts of venture capital, according to their founders.

“Most good borrowers have other good options,” said Dan Miller, co-founder of Fundrise. “Being able to close loans quickly eliminates the extra burden of instantly having to raise capital online.”

The approach has made Fundrise more competitive, he said, adding that the firm’s monthly deal volume more than doubled since it began pre-funding in September. According to Miller, Fundrise, which claims to have raised just under $20 million for projects in New York City alone, is already considering another round of fundraising.

Firms that lack the capital to pre-fund deals appear to have fallen behind.

New York–based iFunding was one of the industry’s pioneers and claimed to be the largest U.S. real estate crowdfunding site until about the spring of 2014. But the firm has so far failed to secure significant financial backing from venture firms. And according to observers, it has since fallen behind rival Fundrise in terms of self-reported monthly deal volume (see related sidebar).

Allen Shayanfekr, CEO of the still self-funded crowdfunding start-up Sharestates, acknowledged that he has lost some deals in part because he doesn’t pre-fund.

“The private lending space is inherently very fast-paced. We typically have a pretty good advance knowledge of deals, but there were instances where we needed to close within a week,” he said.

The tech paradox

Raising money and getting traction in the market is easier said than done. While growing a business and convincing investors to write big checks are essential, achieving both rests on the shoulders of the people behind the firm.

Most sources said that even if a start-up has a great product, if the founders don’t understand the real estate game, they’d be dissuaded from investing.

“You can build lots of great software, but if you don’t understand who your buyers are, you’re not going to have a lot of success,” said Bain’s Bettman, explaining that he chose to invest in Reonomy partly because of its founders’ grasp of the real estate business.

Not surprisingly, a number of the more successful real estate start-ups have their roots in real estate. CompStak’s Mandel, for example, was a broker at commercial firm Grubb & Ellis; VTS’s Romito is a veteran of Murray Hill Properties, and brothers Dan and Ben Miller of Fundrise have a well-connected real estate developer father.

While people skills seem like a prerequisite in any field, in the tech field that requirement highlights a paradox. These new tech platforms are, in many cases, making personal relationships more obsolete by making data and funding widely available via the Internet.

But for now, winning over investors and clients still requires good old-fashion schmoozing.

Still, sources say it’s too early to predict the winners and losers among the latest crop of real estate tech start-ups.

“The consolidation will come after the next downturn,” said Fundrise’s Dan Miller, “and a lot of platforms will not be able to survive.”