After months of rumors and speculation over where Apple and Facebook would plant their flags in New York, Mark Zuckerberg’s firm showed its hand.

The social media giant signed a lease for more than 1.5 million square feet of office space across three buildings at Hudson Yards in mid-November, a major coup for developers the Related Companies, Oxford Properties Group and Mitsui Fudosan America.

Related’s Stephen Winter, senior vice president of commercial leasing, said his firm’s business plan was “executed perfectly” before the Facebook deal. Now, he said, it’s “beyond perfect.”

“Because now,” he said, “it seems that every single major tech company wants to be in and around 34th Street.”

But much suspense remains. Facebook could still follow up its Hudson Yards lease with another big deal at Vornado Realty Trust’s Farley Post Office redevelopment — though it is reportedly facing stiff competition from Apple. And after Amazon pulled out of plans to build a major campus in Long Island City early this year, it was also reportedly seeking space at the massive Penn Plaza building.

How the tech industry’s behemoths divvy up New York’s pipeline of modern, amenity-loaded office space will likely have major implications for where medium- and small-scale tech firms choose to set up shop, sources say.

“Any real estate decision is location-driven, but with tech tenants, what we’ve found is that that tends to be one of the primary drivers,” said Colliers International’s Stephen Shapiro. “In banking or in legal or accounting, you don’t necessarily get that same sense that all the talent wants to be in a two-block radius.”

“Any real estate decision is location-driven, but with tech tenants, what we’ve found is that that tends to be one of the primary drivers,” said Colliers International’s Stephen Shapiro. “In banking or in legal or accounting, you don’t necessarily get that same sense that all the talent wants to be in a two-block radius.”

Cushman & Wakefield (which represented Facebook on the Hudson Yards deal) and JLL (which is leading Apple’s search) declined to comment for this story.

Still, while the leasing appetites of the so-called FAANG firms — aka Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google — have dominated the discussion in recent months, they represent just the tip of a deep ecosystem of young and often high-growth tenants presenting brokers and landlords with a new set of opportunities and challenges.

Landing a high-profile startup as an anchor tenant at a new development has become increasingly competitive. But the rapid rate at which tech firms grow — or contract — can pose risks.

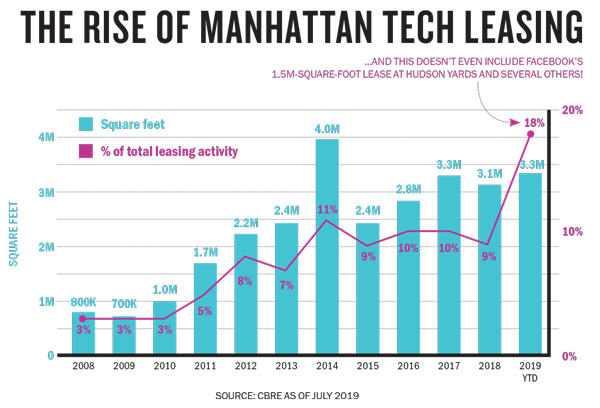

Still, tech leasing in Manhattan has now surpassed 3 million square feet for the third straight year, according to the latest data from CBRE. In 2019, deals from that sector had already passed that mark by July, and subsequent leases (such as Facebook’s at Hudson Yards) mean that the year’s total tech leasing volume will hit an all-time high.

“The Facebook and Amazon stories are incredible, but the bigger story to me is that there are companies that were not here five years ago, that we’d never heard of, that are now taking up massive amounts of space,” said Newmark Knight Frank New York Tri-State Region President David Falk, whose team took over leasing at 1 World Trade Center from Cushman & Wakefield in April and has since brought in tenants including food-ordering platform Olo and equity-management startup Carta.

“The story to me isn’t three tenants — it could be 50 tenants,” he said.

Birds of a feather

The Midtown South submarket — which extends from Park Avenue South and Madison Square Park down to Hudson Square and Tribeca — has long been at the epicenter of Manhattan’s tech leasing boom.

The submarket’s popularity among tech tenants can largely be attributed to the gravitational pull of Google, the first tech giant to carve out a substantial presence in New York.

“We certainly saw a ‘Google effect’ in the neighborhood near Google’s campus, and it really seems to happen wherever there’s a critical mass, where a big tech behemoth establishes itself,” Colliers’ Shapiro said.

Midtown South continued to see big tech deals in 2019, with Peloton inking a 312,000-square-foot lease at Cove Property Group’s redeveloped 441 Ninth Avenue, and Microsoft taking all of the office space, or about 63,000 square feet, at the Nightingale Group and WCP Investments’ newly developed 300 Lafayette Street. Meanwhile, Netflix took another 67,000 square feet at Normandy Real Estate Partners’ 888 Broadway, where it now occupies 100,000 square feet.

At the same time, tighter availability rates in the submarket — consistently at least two percentage points lower than Downtown or Midtown — have been pushing tech tenants to explore other parts of the city. And because of their tendency to cluster, the office-leasing decisions of one pioneering firm can play a big role in establishing an area as a tech destination.

In the Financial District, for example, sources pointed to music-streaming company Spotify’s decision to locate its U.S. headquarters at 4 World Trade Center as a key moment in Downtown’s emergence as a tech hub. The firm first took 378,000 square feet at Silverstein Properties’ 2.3-million-square foot office tower in early 2017 and has since expanded its footprint to 564,000 square feet to become the building’s second-largest tenant.

“Spotify really helped turn the corner for us,” said Jeremy Moss, Silverstein executive vice president and head of leasing. “We had started to become a major destination for the broader TAMI [technology, advertising, media and information] sector, and now we’re seeing a strong commitment from tech in particular.”

Silverstein’s complex has landed a wide range of tech tenants since the Spotify deal, including stock exchange company IEX Group, e-commerce mattress startup Casper and online mortgage provider Better.com, all at 3 World Trade Center next door. In October, fresh off an initial public offering, Uber inked a lease for more than 300,000 square feet at 3 WTC, with plans to consolidate its offices, which are scattered across Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens.

Tech tenants at the World Trade Center now occupy about 1.5 million square feet and employ 15,000 employees, Moss said.

“I think initially, at tech’s infancy in New York City, tech companies were drawn to Midtown South because it’s cheap,” he added. “Now that tech has matured as an industry here, they are gravitating toward new buildings where they have room to grow.”

A similar dynamic may now be in play at Hudson Yards, further spreading the tech leasing footprint into relatively uncharted territory.

“With Facebook signing at Hudson Yards, that is really going to validate Hudson Yards as a destination for tech,” said Zev Holzman, Savills senior managing director.

“Typically, you’ll see that one watershed moment, and then you’ll see smaller tech companies follow,” said Holzman, who recently represented healthcare tech company Flatiron Health in its 250,000-square-foot renewal-expansion at Stellar Management and Imperium Capital’s One Soho Square, nearly doubling the company’s occupancy.

The geographic diversification of tech office leasing in New York has dovetailed with major companies like Amazon, Apple and Facebook facing growth constraints in their home bases on the West Coast.

“A lot of West Coast-based companies are outgrowing their own market, both from the standpoint of available space and from the standpoint of talent,” said Nicole LaRusso, CBRE’s tri-state director of research and analysis.

“And if you’re looking around and thinking, ‘How can I fulfill my ambitious growth objectives? Where do I need to locate to make that happen?’ one of the few choices you have is the New York market.”

Recruitment wars

A key driver in New York’s tech leasing boom has been the region’s talent pool.

A key driver in New York’s tech leasing boom has been the region’s talent pool.

Tech employment in the city has grown by 66 percent since the Great Recession, outpacing all other industries, according to CBRE. Only business and professional services — a broad category, which includes accounting and management as well as call centers and janitorial services — comes close, with a 48 percent increase. Media, finance and legal services, meanwhile, have all grown by no more than 15 percent.

And yet demand for tech talent is still strong, leading to fierce competition among employers. In addition to big salaries, tech firms have been at the forefront of using real estate as a recruitment tool.

“It’s not just tech companies, but I think it’s particularly relevant where you’ve got a tech labor issue that you’re trying to solve,” LaRusso said. “That’s probably where there’s the most competition for employees.”

Related’s Winter noted this dynamic among Hudson Yards’ tenants.

“When companies with offices at Hudson Yards go to college campuses to recruit, to the MITs and Harvards of the world, they talk about Hudson Yards,” he said. “It’s a powerful part of their recruitment and retention of talent.”

That’s given new buildings as well as properties with large, open floor plans a leg up in attracting these coveted tenants.

Sean Black — a JLL, Cushman and WeWork alum who is now is now CEO of his own office brokerage, BLACKre — said any developer bringing a new project to the market is always looking for an anchor tenant.

“It helps to stabilize the building and demonstrate that the building has been approved by a major employer,” said Black, adding that it’s “extremely transformative for a project — especially in new areas, because it shows that an area is on the path of progress to some extent.”

Sources also said that properties that have history tend to appeal to other tech employers.

“They want to be in assets that are interesting in some way, that have some sort of authentic component — like the Farley Post Office — rather than a typical Midtown glass-and-steel skyscraper,” Savills’ Holzman said.

888 Broadway, where Netflix now occupies 100,000 square feet

The full-block Morgan North Post Office building near Hudson Yards, where Tishman Speyer recently closed on a long-term lease from the U.S. Postal Service for the top six floors, is also expected to attract tech tenants, sources said. And in Williamsburg, Heritage Equity Partners and Rubenstein Partners’ 25 Kent is catering to tech tenants, though it has yet to publicly announce a lease.

Marcus & Millichap’s Eric Anton, an investment sales broker, said that when he brokered the sale of a minority stake in St. John’s Terminal to Westbrook Partners in 2006, he could not have imagined that a tech giant would take up 1.3 million square feet there. But Google did just that in July, after new owner Oxford Properties unveiled plans to redevelop the property into an office complex with “abundant outdoor space and greenery.”

“Everybody loves outdoor space now,” Anton noted, adding that “10 years ago, nobody really cared, 20 years ago absolutely no one cared.”

Growth spurts

Unpredictable growth trajectories are, however, par for the course when working with tech firms.

“Every tech company that we’ve spoken to has either grown while we were in the midst of negotiating the lease, or immediately following it,” Silverstein’s Moss said of tenants at 3 WTC.

But there have also been some high-profile busts — none bigger than WeWork, Manhattan’s largest office tenant — which have given some landlords a sense of caution as well.

“Now more than ever, what you need to look at with large technology companies is the risk of a big shakeup, and where that leaves the landlord,” said Mario Faggiano, co-founder of Brooklyn-focused brokerage EXR, which has worked with many TAMI tenants in Williamsburg.

A rendering of the Farley Post Office redevelopment

Faggiano noted that the fundamentals of venture capital investing are being questioned as startups are given tons of money and taking tons of office space before they even have revenue to show for it.

“If they can’t fulfill their lease or they burn through their cash, or if the CEO goes crazy … you have a huge asset that maybe was expected to perform at X and may now be in a different position than initially thought,” he said.

Faggiano noted that the largest tech companies — like Google and Amazon — are generally viewed as lower-risk. But small tech firms tend to have more volatile real estate needs.

“Especially in the beginning stages, as funding becomes available, tech firms need nimbleness to be able to expand and contract,” Colliers’ Shapiro said. “When you get an infusion of capital overnight, you may need to add 200 seats and move out of a co-working space into a permanent space, and that may all need to happen very quickly.”

All of that means landlords and brokers have had to become more comfortable with short-term leases and shrinking the amount of time a company needs to move into a new space.

“From a landlord perspective, the critical item is creating pre-built creative space so that it becomes a plug-and-play,” Shapiro said, “instead of an agonizing decision for the leader of the company to figure out what kind of carpet to put in or what kind of chairs to put in.”

The relative youth of most tech entrepreneurs has also created a shift in the dynamic between tenants and brokers.

“It’s a very exciting time for young brokers, because in some cases the decision-maker may be someone they know personally, or who is closer to their age,” said Falk, a 33-year industry veteran. “When I started in the business and the big tenants were all major Wall Street firms, I was 25 years old, and the decision-maker was 40 years older than me.”

‘Buying’ into tech

The imprint of the tech sector on New York’s office leasing landscape is undeniable.

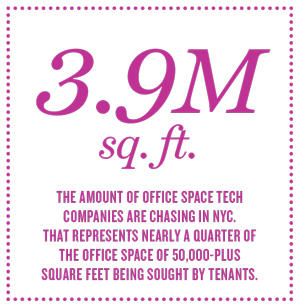

Tech companies are chasing 3.9 million square feet of office space here, according to CBRE’s most recent research report in July. That represented nearly a quarter of the office space of 50,000-plus square feet being sought by tenants.

And as of mid-2019, the tech sector accounted for 18 percent of total Manhattan leasing activity — up from a 9 percent share at the same time last year and a 3 percent share in the early post-recession years.

But unlike VC-backed startups that are often hypersensitive to cost constraints, nontech firms with large tech divisions sometimes have more financial leeway to lease up trendy tech-oriented space, Colliers’ Shapiro noted.

“They may be a little more apt to invest in hip space in areas that may be a little more expensive because they have revenue coming from different business lines,” he said.

Yet while the tech sector has made a run on leasing, it has not yet done the same — at least on a significant scale — when it comes to buying buildings.

There are, of course, some exceptions to that rule. In 2010, Google bought 111 Eighth Avenue in a blockbuster $1.77 billion deal. Last year, the company followed that up with a $2.4 billion buy of Chelsea Market, and in May it snapped up the Milk Building across the street for $600 million.

Amazon’s scrapped HQ2 plans would have gone a step further, with the ground-up development of an office property, while media giant Disney — whose new Disney+ streaming service is competing with Netflix — is planning a 19-story, nearly 1.3 million-square-foot tower at 4 Hudson Square, on a site it acquired from Trinity Church for $650 million in 2018.

“From a pure economic perspective, I’m not sure there are that many companies that could make that same statement that Amazon or Google did, or that Facebook could have,” Shapiro said. “But from a capital appreciation or safety perspective, it’s certainly something most companies would love to do.”

Newmark’s Falk had a similar view.

“Could Facebook have gone with a developer and built a building? I’m sure they could have,” he said. “I’d guess the reason why these tenants haven’t bought is just that they don’t want to deploy capital that way; they want more flexibility. But once you get to the size of a Facebook or an Apple, it becomes a philosophical decision.”