Battle mode may come with the territory when building Long Island’s largest project since Levittown.

Jerry Wolkoff, the often prickly developer behind Islip’s Heartland Town Square megaproject, has skirmished with labor unions, tangled with school boards and combated county officials as he has worked for nearly two decades to create a mini-city on former hospital grounds.

The efforts can seem akin to pushing a large rock up a hill. Indeed, 17 years have elapsed since the $4 billion project was announced, and no new buildings have yet gone up. And a lawsuit from the local Brentwood school district filed this fall still stands in the way, even as Wolkoff recently scored a key rezoning to allow part of the project to proceed.

But feeling under siege is not a new state of affairs for Wolkoff, who in February was slapped with a hefty $6.7 million fine by a judge for prematurely destroying artful graffiti at his 5Pointz rental project in Queens.

“The ruling is wrong, and I plan to appeal,” said the developer, who appears careful not to unnecessarily antagonize rivals but is also prone to tossing off phrases like “it’s insane” and “it makes no sense” about those who oppose his plans.

However, if Wolkoff, 81, who’s developing Heartland with his sons, David and Adam, wasn’t so brash, Heartland might not have made it even this far, observers said.

“It needed someone with a strong stomach, because there was going to be attacks by lots of people,” said Mitch Pally, the chief executive of the Long Island Builders Institute, a trade group. “You also have to have a lot of money to pay the consultants to get you to the finish line.”

To guarantee success for a project that promises a staggering 9,100 apartments, it’s likely helpful that Wolkoff rarely gives an inch on his positions, even if that recalcitrance can frustrate those looking for middle-ground solutions.

“If you had someone who would roll over with every request and demand over the years, Heartland probably would not be economically viable,” said Eric Alexander, the director of Vision Long Island, a planning advocacy group.

Moving in phases

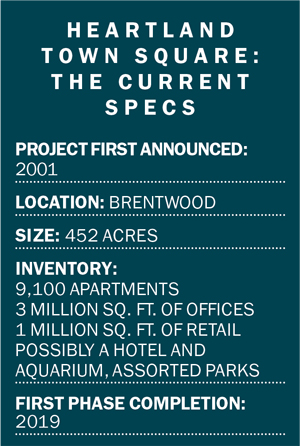

Designed to ultimately contain apartments, 3 million square feet of offices and 1 million square feet of retail, plus assorted parks and possibly a hotel and aquarium, Heartland is planned to cover 452 acres at the junction of the Long Island Expressway and the Sagtikos Parkway in the Brentwood neighborhood.

Once home to Pilgrim State Hospital, the largest mental-health facility in the world when opened in the 1930s, the property was host to more than 13,000 patients at its peak. But the complex dramatically downsized over the years, and today, the hospital — known as Pilgrim Psychiatric Center — is relegated to a cluster of brick buildings on about 80 acres. Heartland Town Square would wrap around the hospital on large meadows where the rest of the medical facilities once stood.

Wolkoff’s grand plans will have to happen in phases. Last July, Islip’s town board voted 5-0 to approve the rezoning needed for a mixed-use community on land that had been zoned for single-family houses.

Wolkoff’s grand plans will have to happen in phases. Last July, Islip’s town board voted 5-0 to approve the rezoning needed for a mixed-use community on land that had been zoned for single-family houses.

But the board would only agree to green-light a first phase of the project, a 113-acre site, which includes a red-brick Depression-era water tower that would be preserved. Phase one is expected to wrap up in early 2019, Wolkoff told TRD.

The town imposed other conditions, too, including that Wolkoff spend $2 million to clear some blighted nearby buildings, reserve nine acres on his site for facilities like a post office and firehouse and put aside $9 million to maintain local roads, according to town documents.

In addition, 10 percent of the apartments at Heartland, which will offer mostly rentals, must be reserved for those making between 80 and 100 percent of the median income in the area, or no more than about $111,000 a year. Meeting that criterion may be relatively easy, but it’s important “so people don’t get locked out of the application process, which happens all the time in the city,” said Wolkoff, who added that the difference between market rate and affordable rents at Heartland would probably be negligible.

And to make good on the project’s pedestrian-friendly bona fides, Wolkoff must also offer shuttle service to the closest Long Island Rail Road station, which is in Deer Park.

Along the same lines, if car traffic isn’t lower than average for a community of Heartland’s size, town officials reserve the right to reduce Heartland’s total office space down the road to cut back on the number of commuters.

“This project changes Long Island’s paradigm,” said Ron Meyer, Islip’s commissioner of planning and development, adding that similar pedestrian-friendly projects afoot on Long Island, like Wyandanch Rising and the Ronkonkoma Hub, prove a trend is gathering steam.

Trade troubles?

As the project progresses, Wolkoff, who has a history of conflicts with labor unions, may face problems over the hiring of construction workers in Brentwood.

The Building and Construction Trades Council of Nassau and Suffolk Counties, an influential labor group made up of about three dozen unions, has for years demanded that Wolkoff guarantee that all construction jobs related to Heartland be filled by union workers.

In all, Heartland’s construction will generate as many as 800 jobs per year over the next three decades, according to projections from Islip officials.

But for his part, Wolkoff says he wants more flexibility over hiring so that he’s not locked into using only union labor. Union workers can cost 25 percent more than their nonunion counterparts, brokers say.

“I’m not against unions,” Wolkoff said. “It’s just that I’m building this project in a not-rich area, so I won’t be able to charge a lot, and so I have to make sure the price makes sense.”

Wolkoff, who often peppers his language with curse words, added, “I don’t sign project-labor agreements. It’s my money. It’s my land. They’re going to dictate to me? It’s insanity.”

Pally, of the Long Island Builders Institute, called these kinds of comments typical of Wolkoff’s blunt style. “He is not the simplest man to negotiate with, and he would be the first person to tell you that,” Pally added. “And that has its good points and maybe not so many good points.”

On the union side, there may be signs of détente. Matthew Aracich, who in January was sworn in as the new president of the Trades Council, said he’s willing to negotiate. “There is always a position you can take that is beneficial to both sides,” Aracich said. “Is it going to be completely what you want? No. Is it going to be completely what I want? No.”

Wolkoff admits his antipathy toward sweeping labor agreements is a reason Heartland has been slow to take shape.

As part of the approvals process for Heartland Town Square, Wolkoff agreed to design the new construction around a Depression-era water tower, pictured here in a project rendering.

The position also seems to have gotten him into trouble on other jobs. At 5Pointz in Queens, Wolkoff told city officials he would use 100 percent union labor in exchange for being allowed to construct a larger building, adding 400 apartments, for a total of 1,115 units. Activists were riled when reports claimed that not all of the workers at the site were union members.

“Jerry Wolkoff lied to me,” said Jimmy Van Bramer, a City Council member who represents Long Island City, during a 2016 union protest at the 5Pointz site, according to news reports. “Jerry Wolkoff lied to every single New Yorker. Jerry Wolkoff, I will never believe another word you ever say.”

Wolkoff declined to comment about the particulars of 5Pointz. “That’s a whole ’nother story for another time,” he said.

Getting schooled

Communities near Heartland, which is equidistant from Manhattan and the Hamptons, seem supportive of the development. Not so for the local school system.

In November, the school district that covers Heartland sued Islip over the rezoning that made the project possible. Officials there “failed to identify and take a hard look at relevant areas of environmental concern, including the educational, social, demographic and economic impacts of Heartland upon the school district and its neighborhoods and citizens,” according to the 45-page complaint, which also names the Wolkoff family as defendants.

The linchpin of the argument by the school board, formally known as the Brentwood Union Free School District, is that Heartland will funnel about 7,300 children into Brentwood’s school system, based on an internal audit conducted by the board, said district spokesman Felix Adeyeye. As of last fall, a whopping 19,457 students were already enrolled in pre-kindergarten through high school across 17 school buildings in Brentwood, making it the largest suburban school district in the state, Adeyeye said.

As it is, the schools’ capacity is strained, according to a statement. State aid is expected to remain flat, and revenue from Heartland, currently paying a reduced property tax of about $1.6 million per year, is not expected to be much help, the statement said. Brentwood’s annual school budget is $394 million, according to Adeyeye.

But Wolkoff, who predicts that his apartments will be popular with millennials and empty nesters — two groups that don’t usually live with kids — asserts that the development will house far fewer students than Brentwood estimates. Wolkoff puts the potential number closer to 1,800.

He also said that since 2002, when he closed on the site, he has contributed close to $15 million in taxes to the school district. “What have they done with the money I gave them already? Did they put it aside?” Wolkoff said. “The school district has no clue whatsoever.”

He also unequivocally ruled out building a school on his site to handle extra kids, as some have suggested. “Absolutely not” was his answer.

The school district’s suit, filed in the Supreme Court of Suffolk County, was supposed to have its first hearing in January, but the defendants requested a delay, Adeyeye said. For his part, Wolkoff said he isn’t focused on the court battle. “Their case makes no sense, so really, I don’t pay attention to it,” he said.

The thick of it

Despite the raft of conflicts, Wolkoff seems fully committed to seeing Heartland through.

“I have the best piece of property in the New York area,” he said, citing his lifelong strategy of siting projects in the geographic centers of communities, leading to his frequent use of the Heartland name.

After founding his development firm in 1956 with an investment of $15,000, Wolkoff built two-family houses in Canarsie and East Flatbush, Brooklyn. Then he set out for Staten Island. The middle of the island, near the Staten Island Mall, is home to his Heartland Village, a subdivision of two-family houses built in the 1960s.

Raised in Brooklyn, Wolkoff said he has never developed apartments in Manhattan because he likes building for working-class people. However, his choice of locale for his full-time personal residence — the Hamptons — is decidedly different than the areas in which he prefers to build.

While residential development defined his early career, Wolkoff is also known for industrial projects, and the most significant ones are on Long Island.

Tucked near the Long Island Expressway is Heartland Executive Park in Hauppauge, a 240-acre, 75-building industrial park. And next to the proposed site of Heartland Village is the 400-acre, 40-building Heartland Business Center, with its Heartland Golf Park. It’s also home to Wolkoff’s office, which has about 20 full-time employees.

Wolkoff is also now adding two new structures to the business center, a 50,000-square-foot building for a single tenant he declined to name and a 230,000-square-foot structure, which is being built on spec, he said. “There is such a thing as somebody who loves money. That’s not me,” he added. “I like money, and I do enough to take care of me and my family.”

Wolkoff was able to pick up the Pilgrim spread for Heartland Town Square for a relative song: The $20 million sale price works out to about $47,000 an acre. He has no loans, so he hasn’t been forced to immediately profit from the land, agents said.

A well-honed strategy might also be playing out. “He generally doesn’t sell a thing. He’s interested in a very long-term hold, and he would like to see the land held by his family in perpetuity,” said Peter Palazzo, the president of Fuller Construction, an affiliate of Louis Cappelli’s development firm. Fuller is currently managing the 5Pointz project.

After years of back-and-forth battles, Wolkoff seems to be learning to bend a bit, like with his agreeing to the Islip town board’s demand to build his project in phases.

“He is certainly no wallflower, but he has listened,” Alexander of Vision Long Island said.