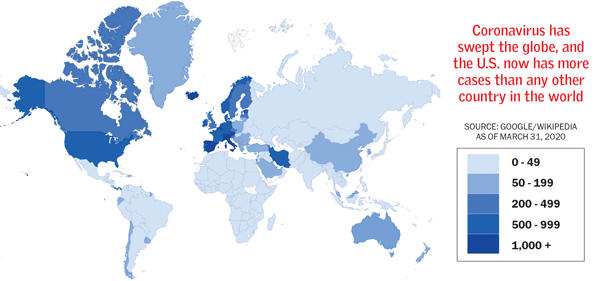

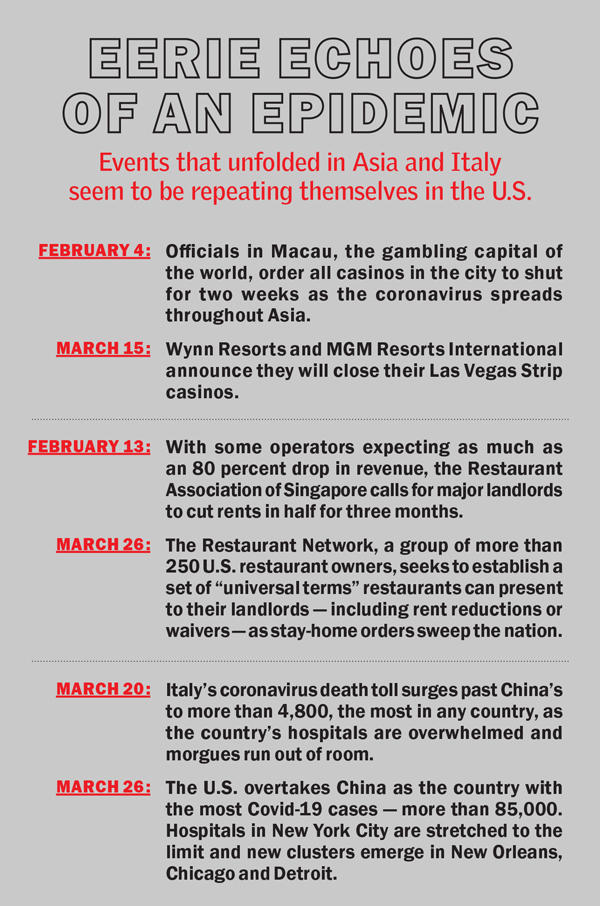

The United States is now at the forefront of the coronavirus pandemic, after weeks of watching from a distance as it engulfed one country after another. China, South Korea and Italy took turns as epicenters of the outbreak with cases spiraling out of control and their economies shuddering to a halt.

It’s now America in the spotlight with the most cases in the world and escalating containment measures threatening higher unemployment than during the Great Depression. Goldman Sachs projects that the U.S. economy will contract by an annualized 24 percent in the second quarter alone — and that was before the White House announced the extension of “social distancing” guidelines through the end of April and maybe even into June.

The uncertainties around the spread of the virus and its economic impact are likely heading toward a peak, as both now teeter on apparent tipping points, but the experience of those earlier epicenters might offer some insight — if not much reassurance.

Looking at how those harbinger countries acted to contain the virus and how their outbreaks have affected their markets presage how things could play out here, depending on what we do.

Read more

“We know that a pandemic, by definition, is borderless,” said Susan Bazak of Bazak Consulting, an emergency management firm that has written pandemic planning guidance for building owners and operators in North America and China. “Commercial real estate, no matter where it is located, like all other business sectors, will face common stakeholder and operational challenges.”

Inhospitable

The hospitality sector was the canary in the coal mine for the effect of the coronavirus outbreak on U.S. real estate as the plunge in travel dropped average occupancy rates to near 30 percent across the country and into the teens in New York City.

But Asia’s travails suggest the worst is yet to come.

“As of mid-March, occupancy in many hotels is in the single digits,” CBRE Asia Pacific analysts wrote in a recent report.

Observers of U.S. markets clearly expect similar damage. On March 23, Kroll Bond Rating Agency assigned an “underperform” outlook to all CMBS loans backed by a single hotel property or portfolio, pointing to single-digit occupancy rates in Chinese and Italian hotels.

“If occupancy levels among [these] lodging properties fall to this level for an extended period, none would be able to achieve break-even debt service coverage,” Kroll analysts wrote.

Indeed, figures from real estate data firm Trepp show more than half a dozen hotels in New York City had a debt service ratio below 1 even before the coronavirus pandemic hit, meaning cash flows weren’t sufficient to cover debt payments.

But it will take longer to see the impact on other sectors of real estate — a point made in a Cushman & Wakefield research report published in early March.

“The commercial real estate sector is not the stock market. It’s slower moving and the leasing fundamentals don’t swing wildly from day to day,” the report said.

Korean drama

In contrast to the slump in New York City last year, residential property prices in the South Korean capital Seoul surged throughout 2019 — so much so that the government took drastic action in December to cool the market, banning mortgage lending for apartments worth over 1.5 billion won ($1.27 million). And commercial investment sales in Seoul hit a record high of 16 trillion won, according to investment firm CBRE.

The coronavirus outbreak hit South Korea’s fourth-largest city, Daegu, in mid-February, however, and the real estate business immediately seized up nationwide.

The country’s apartment market saw an average of just 458 deals per day nationwide in the first nine days of March, down from 2,272 per day in December — an 80 percent drop, local business outlet ChosunBiz reported, citing government statistics.

The decline was even starker in Seoul, where daily deal volume fell by 90 percent from 309 to just 31.

“Business is frozen as more people are postponing moving plans because of the coronavirus, or are hesitant to show their homes to strangers out of fear of contagion,” a real estate broker in Seoul’s central Seongdong district told ChosunBiz.

Across the river in the high-end Gangnam district, many brokerages have simply closed their doors.

That’s despite South Korea being relatively successful in containing the virus early without completely shutting its economy down — a feat attributed to an aggressive early testing regime and selective quarantines.

The U.S. missed its window to contain the outbreak through testing, however, and is still struggling even to deploy and process testing kits to track the spread.

With South Korea’s outbreak on the wane, the country is beginning to inch towards normalcy, but Seoul’s formerly high-flying property market won’t be recovering anytime soon.

“Home prices could fall by 4 to 5 percent in the second half of the year,” Song Inho of the Korea Development Institute told local media.

Lombardy lockdown

Last year was also great for real estate in Milan. Office leasing hit an all-time record of 5.2 million square feet and office investment reached an all-time high of 3.6 billion euros ($4 billion). On the residential side, Milan stood out as the only large Italian city to see rising home prices, thanks to a wave of luxury development.

“Why Is Milan’s Real-Estate Market So in Fashion Right Now?” asked the Wall Street Journal on Feb. 19, when Italy still had only one confirmed case of coronavirus. But things changed fast.

By March 9, Italy had more than 9,000 cases — most of them in Lombardy and its capital Milan — and the government imposed a nationwide lockdown. As the month went on, new data began to paint a stark picture of Italy’s real estate market. According to analysis from Italian consulting firm Nomisma, annual residential transaction volume could fall by up to 18 percent this year.

Commercial real estate investment in Italy is expected to take an even bigger hit, as Milan accounted for nearly half of all investment in the country before the crisis and much of it was driven by foreign buyers. Nomisma projected that Italian CRE investment could fall by more than half this year, to just 5 billion euros.

The day after imposing the lockdown, the Italian government also put a moratorium on mortgage and other debt payments to help consumers and businesses cope. A similar measure, but covering rent as well, is now gaining traction in Albany (see related story on page 28).

Italy’s March 9 national lockdown closed all schools, universities, restaurants, bars and theaters, canceled all sporting events and postponed religious ceremonies, funerals and weddings.

The guidelines issued by the White House on March 15 don’t go nearly as far. They are merely recommendations to avoid nonessential travel, going to work, eating out or gathering in groups of more than 10.

By late March, the World Health Organization indicated that Italy’s quarantine measures were slowing the growth of new cases and flattening the proverbial curve. But at the same time, Italians were bridling at the two-week-old restrictions and beginning to flout the rules, the Associated Press reported.

Fearing that a breakdown would again unleash exponential contagion, public officials pleaded for patience and fortitude.

“By now, we have understood,” tweeted Milan’s mayor, Giuseppe Sala, “this is a marathon, not a sprint.”

How China recovered

In mainland China, where the coronavirus epidemic began and has since subsided, officials have already begun the tricky process of opening the country back up for business while the rest of the world is still reeling from outbreaks.

It took two months of heavy-handed quarantine to subdue the virus there, but the White House’s voluntary “social distancing” guidelines — or even New York State’s aggressive stay-home orders — would not likely achieve that result.

China only managed to contain its outbreak through a draconian regime that would never even be contemplated, much less tolerated, in America.

Starting February 2, Chinese authorities began forcibly quarantining not only mild and suspected cases but even healthy close contacts of confirmed cases, interning them en masse in makeshift quarantine centers, the Wall Street Journal reported.

In fact, Chinese health officials warn that even Italy’s strict lockdown won’t effectively contain the spread, according to Bloomberg. That’s because Italy sends mild cases home to self-quarantine, in order to spare overburdened hospitals, but the Chinese experience shows that only assures that the virus spreads to the entire household.

Many countries that balk at the thought of internment camps are actually spreading the coronavirus by confining mildly ill patients to their home, according to the WHO.

“Due to lockdown, most of the transmission that’s actually happening in many countries now is happening in the household at family level,” said Mike Ryan, head of health emergencies at the WHO, at a March 30 briefing.

Reality check for U.S.

In the United States, President Donald Trump backed off his notion to have the country “opened up” by Easter Sunday, April 12, to minimize the economic damage. In a somber address from the Rose Garden March 20, Trump confirmed that that social distancing guidelines will remain in effect through the end of April, and possibly June, on the recommendation of his public health advisers.

The day after Trump originally announced the guidelines on March 15, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, explained why it is so difficult to do the right thing in a pandemic if you only see the present without considering what could happen in the future.

“Some will look and say, well, maybe we’ve gone a little bit too far,” Fauci said. “The thing that I want to reemphasize, and I’ll say it over and over again, when you’re dealing with an emerging infectious disease outbreak, you are always behind where you think you are if you think that today reflects where you really are.”