For years, wealthy buyers of Manhattan real estate have gone to great lengths to remain anonymous. But last month, the U.S. Treasury Department sent a chill through the New York luxury real estate world when it announced that it would require hidden buyers of high-priced properties to reveal themselves.

The new rule — which will be piloted in Manhattan and Miami-Dade County between March and August — is aimed squarely at uncovering money laundering in two markets that have been propped up by foreign investors.

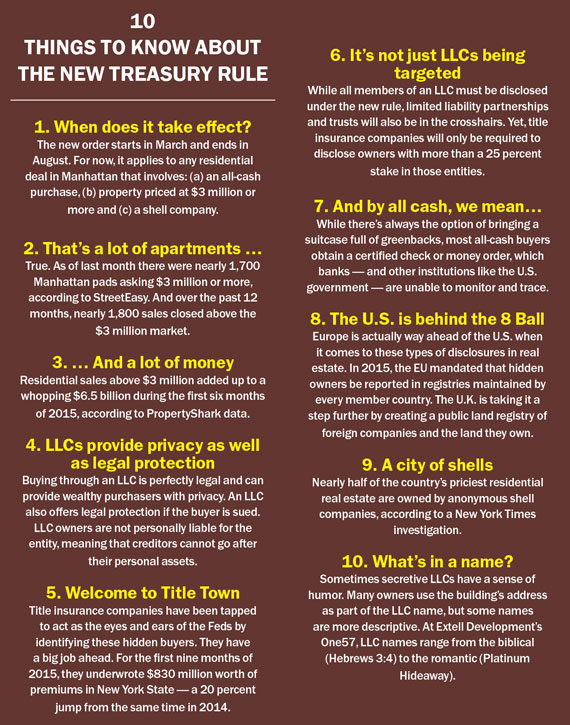

In Manhattan, the mandate will apply to buyers purchasing properties priced at $3 million or more — as well as paying in all cash and using a shell company, such as a limited liability corporation, to shield their identity.

Not surprisingly, the news did not sit well with those who work in the Manhattan luxury market.

Manhattan real estate attorney Ed Mermelstein, who works extensively with Eastern European buyers, said the regulation would “scare possible investors from overseas.”

And Michael Graves, a Douglas Elliman broker who said the bulk of his deals above $8 million are all-cash LLC trades, believes only a tiny fraction of purchases are done with dirty money. High-profile business executives and celebrities, for example, routinely use LLCs to purchase real estate, both to maintain privacy and because LLCs provide legal and financial protection if the buyer is sued.

“The vast majority of these transactions are simply people who want to protect their identities for the safety of themselves and their family,” Graves said. “By and large, the Feds will find it’s a witch hunt.”

The federal government obviously sees things differently and is looking for the bad actors, even if they are few and far between. Under the new order, regulators will collect ownership information via title insurance companies in the hopes of tracing illicit funds to the drug trade, terrorist entities or others. The government will rely on title insurers to collect the data, which they contend will not be disclosed to the pubic.

“They will find the needles in the haystack and find it’s worth scouring through more haystacks to find more needles,” said Marc Landis, managing partner and chair of the real estate practice at Manhattan-based law firm Phillips Nizer.

Following Wall Street

The rule essentially turns to title insurance companies to act as the government’s eyes and ears.

It will require those firms to disclose all members of an LLC in these $3 million-plus, all-cash deals. For other legal entities, such as limited liability partnerships or trusts, title companies must disclose all “beneficial” owners — or individuals who own 25 percent or more of the equity interest of the entity.

“That’s more exacting than you would otherwise expect to see,” said Bob Axelrod, a director of Deloitte’s anti-money laundering practice, referring to the strict standards for reporting all LLC members.

But even with the new rules, federal regulators are still playing catch-up when it comes to overseeing real estate, especially compared to the highly regulated banking industry, which has seen regulations ramp up since 9/11, when concerns about the financing of terrorism flared up.

For example, since 2001, the Patriot Act has required banks to identify beneficial owners of private bank accounts opened by non-U.S. citizens and to record transactions from parts of the world where money laundering is a concern like Central America and parts of Africa and the Middle East.

From left: David Cameron. Michelle Korsmo and Jacob Lew

In the wake of the financial crisis of 2008 — which sparked concerns about overleveraged banks — the Dodd-Frank Act added another layer of regulations intended to improve “accountability and transparency” in the financial system.

And back in August 2014, the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, which is known as FinCEN, proposed a rule that would require banks, broker-dealers, mutual funds and others to reveal and verify the identity of customers. The rule is expected to take effect this year. (Previously, financial institutions made their own risk-based assessments.)

“The financial services world is heavily regulated to protect people’s money and to protect the economy of the United States,” said Ed Wilson, former acting general counsel at the U.S. Treasury and now a partner at the Washington, D.C.-based law firm Venable LLP. “Real estate folks have not been regulated as much.”

The banking industry is not the only one ahead of the real estate industry on the regulation front. Oversight of real estate here has also lagged behind international counterparts, with Europe leading the way. In 2015, the European Union passed a directive requiring similar disclosures to what the U.S. Treasury is piloting. Under the EU rule, beneficial owners of companies and trusts must be reported in central registries in each EU country. In the United Kingdom, anti-corruption advocates have pushed for even more transparency. The efforts paid off this past July, when British Prime Minister David Cameron said the U.K. would introduce a central public land registry of foreign companies that details what land they own.

This new wave of disclosure mandates has come on the heels of a broader international push to crack down on money laundering. Two years ago, an international anti-money-laundering group organized by representatives from 36 countries, known as the Financial Action Task Force, recommended beneficial owners be disclosed for shell corporations. Those suggestions were not lost on U.S. officials.

“You have international pressure to get to beneficial owners; you have programs that say you have to do this in banks,” Wilson said. “And then you have local pressure, with states and cities saying, ‘Our housing markets are going crazy with people paying exorbitant sums of cash. Where is it coming from?’”

Buying in secret

Here in New York City, these new regulations stand to impact a large (and growing) group of buyers — if they’re permanently adopted.

In 2014, 54 percent of Manhattan residential properties that sold for $5 million and up were bought by secret buyers, according to the New York Times.

And as of last month, nearly 1,700 Manhattan properties on the market were asking $3 million or more, according to StreetEasy. In addition, new development condos — the products of choice for foreign buyers who often favor LLCs — have seen especially large price gains. During the fourth quarter of 2015, the average sales price of new development was $3.3 million, according to appraisal firm Miller Samuel.

Jonathan Miller, the president and founder of Miller Samuel, said the new rule could cause hiccups in a high-end market that’s already showing signs of softening.

“The problem is that you’re casting this blanket of uncertainty over a market that’s already slowed from a year ago, based on some small percentage of bad players,” he said. “The best-case scenario is that it has no impact [on sales]. The worst case is that it slows down the activity a little bit until people feel comfortable about it. The consumer is probably going to wait six months to see if

this renews.”

Meanwhile, Howard Lorber, chair of Elliman and an increasingly active developer, shrugged off the changes entirely. “We think that this will have little effect on the market,” he said. “It is de minimis and will not have a significant impact.”

Phillips Nizer’s Landis speculated that FinCEN’s latest order could in fact become permanent.

“While the order said it’s for six months, I would suspect they would continue if they get the information they need. If not, they will tighten it up in some fashion,” he said.

Once officials work out the kinks, Landis added, they will likely expand to other high-end markets such as San Francisco, Silicon Valley and Boston.

Title insurance in the spotlight

For title insurance companies, the new order means an end to business as usual. It also puts the normally under-the-radar sector in the spotlight.

Yet the Treasury’s move to use the title insurance industry makes sense because almost every real estate buyer purchases title insurance, making it the only entity that touches almost every transaction. While these firms are not currently required to know who is behind the LLCs that they may be insuring, that will change under the new guidelines.

While the industry has publicly supported FinCEN’s attempt to stop the flow of illicit funds into New York real estate, it also conveyed concern about how it would be implemented and enforced. In a Jan. 13 letter American Land Title Association (ALTA), a national lobbying group led by Michelle Korsmo that represents more than 5,500 title companies, asked FinCEN to limit disclosure requirements. Sources in the anti-money-laundering industry speculated that if the order becomes permanent, a cottage industry would pop up to help title companies meet federal demands.

While the industry has publicly supported FinCEN’s attempt to stop the flow of illicit funds into New York real estate, it also conveyed concern about how it would be implemented and enforced. In a Jan. 13 letter American Land Title Association (ALTA), a national lobbying group led by Michelle Korsmo that represents more than 5,500 title companies, asked FinCEN to limit disclosure requirements. Sources in the anti-money-laundering industry speculated that if the order becomes permanent, a cottage industry would pop up to help title companies meet federal demands.

Christopher Faherty, a senior manager with Ernst & Young’s fraud investigation and dispute services practice, said that going forward title insurance firms will face “reputational and regulatory risk” if they’re out of compliance. “The reporting requirement means that title insurance companies will likely be required to provide names of potentially nefarious characters to law enforcement,” Faherty said. “Stakeholders will turn to vendors specializing in anti-money-laundering compliance to help mitigate these risks.”

But Jody Fay, managing vice president and chief counsel of the Kesley Co., a title insurance firm affiliated with suburban brokerage William Raveis Real Estate, said it’s too soon to say how the requirement will impact business. “We’re waiting for instructions on how we’re going to implement [the rules],” she said.

Many title insurers told The Real Deal they use their own moral compass when insuring deals that may involve money earned or obtained through illegitimate means. “If it smells to me, I turn it down,” said Eden Esip, president of Titles of New York, who vets buyers using court records and federal crime watch-lists. “I can see where the Feds are coming from; I just think they’re leaning on the wrong party for the information,” Esip said. “A smarter choice would be for them to look at the developers … for obtaining the information.”

Attorney Jonathan Adelsberg of the law firm Herrick, Feinstein said it’s in developers’ best interest to vet buyers early on, regardless of the new rule. “When you sell an apartment — especially given the caliber of some [developers] — no one is going to sign a contract without knowing the ultimate purchaser,” he said. “The last thing a developer wants to do is find themselves in a dispute with a buyer who doesn’t have the financial wherewithal to close.”

He said many commercial contracts today have an Office of Foreign Assets Control provision, meaning that buyers are screened to ensure the source of their funds is legal. The practice has not caught on in the residential market. As for brokerages, Stuart Siegel, president and CEO of Engel & Völkers New York City, said the firms “don’t have that ability or capacity” to screen buyers. He said some of his agents work with representatives of buyers and don’t even know the identity of the actual buyer.

“What we do know is whether that client has the capacity and is bona fide — and that they can pay the price,” he said.