Last summer, when the weather was especially pleasant, I decided to walk along the Hudson River from 72nd street, near where I live, all the way down to Battery Park. Despite redevelopment along the waterfront in recent years, the scenic experience along the 10-mile stretch still feels uneven. Because despite all the boosting that one hears, the development of the aquatic rim of Manhattan, especially along the Far West Side, is very much a work in progress. There are, to be sure, lovely parks, from Riverside Park to the newish Hudson River Park a little farther to the south. But the problem is that there are also massive mile-long gaps that interrupt those sylvan settings. And so, one minute you are admiring exotic grasses and the breeze coming off the water, only to be jolted back to urban reality the next minute by oncoming cars, profane cyclists, smog and cracked concrete.

But one ambitious project on the Hudson promises to deliver a public space that will lead people away from such distractions. Construction on the long-talked-about Pier 55, a 2.7-acre offshore park largely funded by media billionaire Barry Diller and his fashion mogul wife, Diane von Furstenberg, is expected to commence this summer. The roughly $200 million private-public initiative, to which Diller and von Furstenberg have pledged a minimum of $113 million, aims to take an aging pier and build an island oasis that has been described as a floating garden. In April, the project overcame a major legal hurdle after a state judge tossed out a lawsuit that charged that plans for the private-public initiative were not sufficiently transparent. Soon after, the organization charged with spearheading the pier’s redevelopment, the Hudson River Trust, announced that Pier 55 had been greenlighted by the Army Corps of Engineers. The target completion date is now 2019.

A decidedly high-concept new park, it has been designed by Thomas Heatherwick and the landscape architecture firm of Mathews Nielsen. Heatherwick was responsible for the cauldron of flaming pedals used in London’s 2012 Olympics. Lately, he is known as the creator of the yet-to-be-revealed sculpture at Hudson Yards, which has been touted by Related Companies as the next Eiffel Tower. Meanwhile, Nielsen’s firm has done work in New York for Battery Park City and the Spring Street Plaza, as well as Lincoln Center and the Museo del Barrio.

Thomas Heatherwick

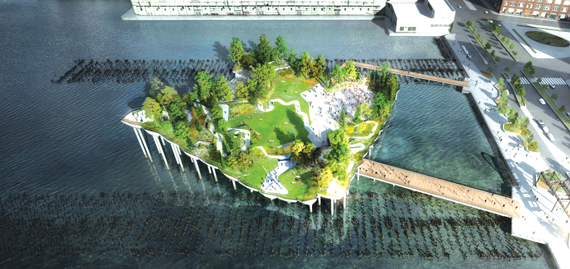

Even with such distinguished credentials, the design team is stepping into unprecedented territory with Pier 55. Not only will the present project represent the first permanent artificial island to extend from Manhattan, it will draw clamorous attention to its own artifice. Its principle aesthetic conceit, after all, is the jarring and potentially delightful incongruity of a patch of greenery, with a variety of tall trees and winding rustic paths, rising up from the middle of a river and sitting atop a sequence of 300 15-feet high, white gleaming pylons lapped by the waters of the Hudson. Meanwhile, its undulating terrain will rise as much as 50 feet above the water in certain places. The designers at Mathews Nielsen said that the landscape is apparently inspired by Acadia National Park in Maine and the general form of the park is intended to suggest a “leaf floating on water.” It is this leaf-like configuration that explains those undulating curves that are the defining feature of the project. Although each part of the site flows into its neighbors, conceptually it is divided into four parts with unique flora. The design of Pier 55 seems to take its inspiration from one of the best-kept secrets of Lower Manhattan, the Irish Hunger Memorial, completed in 2002 to designs by the artist Brian Tolle, together with Gail Wittwer-Laird and 1100 Architect. The half-acre plot near Battery Park City is made up of vegetation and stones from all the counties of Ireland. Like the plans for Pier 55, it is an island of undulating greenery rising over an aggressively artificial base — not white pylons but gray slate rectilinear walls perforated by lines of LED lights. That the designers at Matthews Nielsen should have learned from this worthy precedent in no way demeans their claims to originality.

It’s important to note that Pier 55 will feature an amphitheater, one of several performance spaces in the park, that will reportedly seat about 700 people. In answer to concerns that Pier 55 might become an exclusive preserve for wealthy Manhattanites and artists, the Hudson River Park Trust says it is determined to make more than half of the park’s events free and fully open to all comers.

A rendering of Pier 55

Equalizing access is important. After all, the larger goal of Pier 55 is to bridge the longstanding divide between Manhattanites and the water. Many New Yorkers, I suspect, do not realize how thoroughly the nature of Manhattan has changed over the last half century. Ships were once an integral part of the city’s industry as well as its landscape. Goods arrived from all over the world at the port of New York and from there they went by rail to all parts of the country. As the lifeblood of the city’s industry, the water was something to look at. During the 19th century, the masts of sailing ships billowed in dense clusters all the way from the southern tip of the island up both the east and west sides, well beyond midtown. By the early 20th century, steamships took the place of sails.

By then, New York’s shipping business had already been in steady decline for some time thanks to the emergence of railroads. Beginning in the 1930s, pedestrian access to water was challenged by several Robert Moses-era projects like the FDR Drive and the Henry Hudson Parkway. Then, in the late 1960s, the invention of massive shipping containers killed the shipping industry and forever changed the city’s relationship to the water. At once the magnetic poles of Manhattan shifted inward, causing the waterfront to become increasingly desolate and decayed. For nearly two generations, the rim of Manhattan became the domain of cars rather than pedestrians. Only in the past two decades or so have developers and the city begun to rebuild those derelict spaces. The various installments of the Hudson River Park, starting in 1998, have led the way in this process, as has the development of the East River Waterfront Esplanade on the opposite side of the island. Together, these projects along with Pier 55 can reclaim in the name of leisure what had once been claimed in the name of commerce.