The nightmare began a year ago.

After rebuffing Compass for several years, a New York agent finally gave into temptation.

“They sold the dream,” said the agent, who spoke on the condition of anonymity and said they were offered a lavish bonus and generous perks. But one year into a three-year contract, the agent, frustrated by what they saw as lack of support from the firm, wanted out.

But it won’t be easy to leave. As far as the agent can tell, if they left, they’d be on the hook to Compass for $400,000.

It’s a startling figure. Yet the agent’s predicament is common in brokerage, where for decades companies have used clawbacks — a contractual provision to recoup already-paid financial incentives from departing agents. But given Compass’ extraordinary growth story, with the firm’s huge recruitment push and industry-leading sweeteners, the problem is particularly pronounced.

More than 20 current and former Compass agents, most speaking on the condition of anonymity for fear of retribution or due to nondisclosure agreements, told The Real Deal they’ve agonized over the financial consequences of leaving. Some agents recounted becoming emotionally and physically distressed when they saw what they would owe. Some wrote the biggest checks of their lives or relinquished thousands of dollars in earned commissions in order to leave the brokerage. One agent said they broke down crying; another vomited.

“Some people feel tied in, and some of them are,” said Mike Golden, co-founder of @properties, a leading Chicago-based brokerage planning to franchise its brand nationally.

The New York agent who owes $400,000 accepts the blame for failing to scrutinize the agreement but said their prospects for repayment are bleak.

Many of the middle-of-the-road producers who joined Compass over the last few years now face repaying these five- and six-figure sums on their own. Though many brokerages compensate agents for lost commissions when they switch firms, the practice is typically reserved for top producers.

“I’m a good agent, but I’m not making $5 million gross commission income,” the agent said. “I’m not Fredrik Eklund here.”

The experiences indicate a troubling pattern to labor experts. The large sums of money agents are on the hook for and the duration of the clawback policy are “incredibly punitive,” said Alexandrea Ravenelle, a sociologist who wrote a book about workplace rights in the gig economy.

“The numbers that Compass is working with here feel, quite frankly, like it’s meant to lock people in,” she said. “I’ve heard of golden handcuffs, but this kind of brings a brand new meaning to it.”

Compass rejected the claim that it locks in agents and said its policies are in line with industry standards.

But the agent accounts run counter to the story the firm tells about itself: that it’s changing the brokerage business and has the best retention rate in the industry because it empowers agents above all else. In a 2018 appearance on CNBC, CEO Robert Reffkin claimed Compass retained 98 percent of agents. “Our only customer is the agent,” he said. “If people weren’t happy, weren’t getting the support and tools they need, then they would leave.”

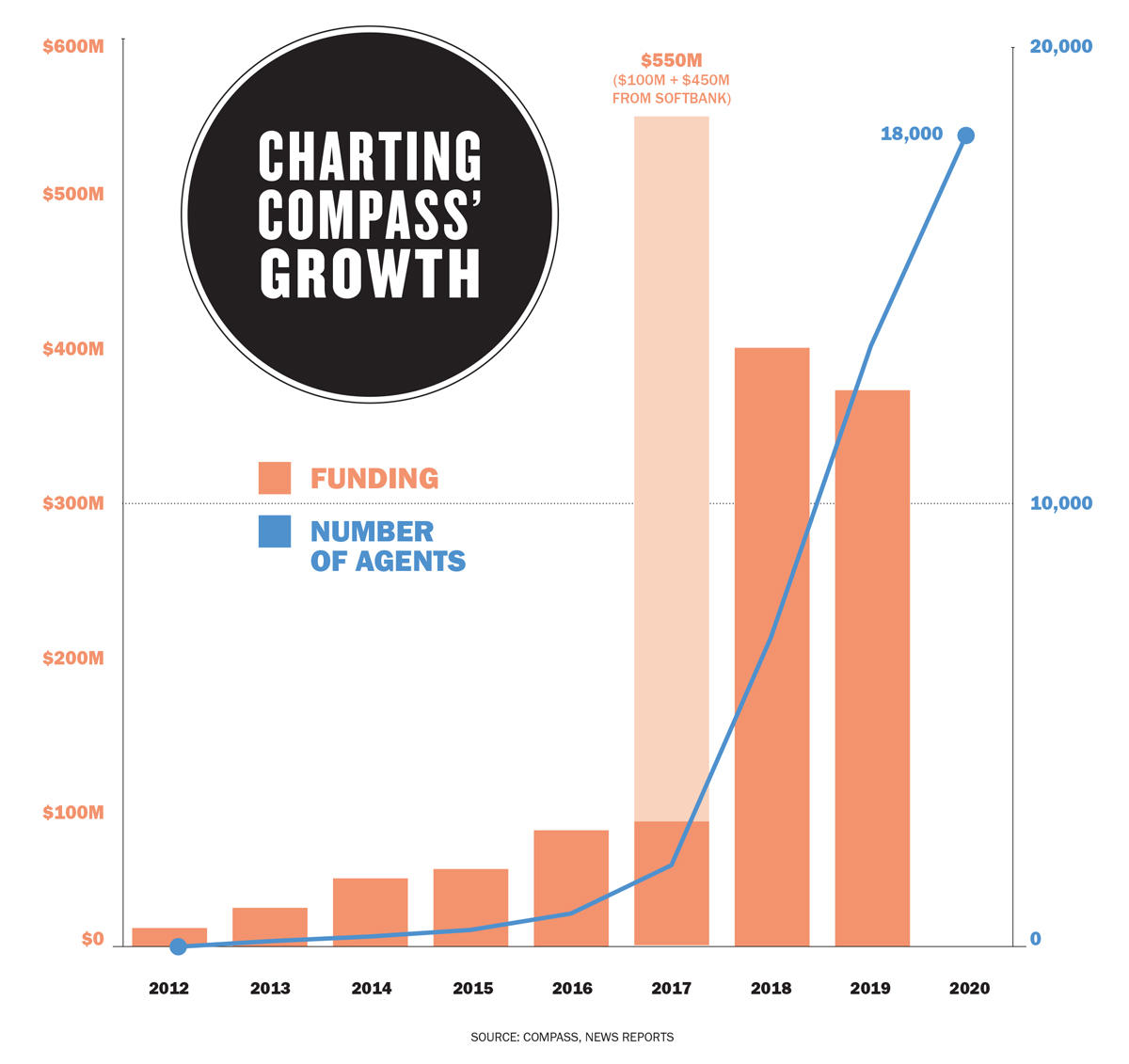

Losing agents is not an option for Compass right now. The fast-growing firm — which has become the third-largest brokerage in the U.S. by deal volume in less than a decade since launch — is on the cusp of a public offering. In order to be valued as a technology company as opposed to a traditional brokerage, Compass will have to demonstrate explosive growth, which a large headcount helps ensure.

“Agents — and not technology — sell houses. The entire business and investment thesis is based on forward momentum and rapid growth,” said Mike DelPrete, an industry analyst who has studied Compass’ model and argued that agents drive revenue and, ultimately, valuation. “Compass can’t afford to slow down.”

Caught in a contract

One agent in Texas paid nearly $70,000 to leave Compass — half of what they earned in a year.

The agent admitted to being so enthralled by the firm’s offer that they signed the contract without consulting a lawyer. It was only when the agent gave notice that they learned the one-year contract had a three-year clawback that applied to all marketing, administrative and office expenses. In other words, the agent may have signed a contract effective for 12 months, but the agreement stipulated the agent must repay any incentives within three years of receiving the benefits if they leave.

“They told me, if you decide to just stay … all of this will go away,” said the agent. “They knew they had done me wrong … and they were still holding that piece of paper over [my] head.”

Independent contractor agreements vary widely by firm and region, and most residential firms roll back commission splits on pending deals. (For example, a departing agent would receive a 40 percent split instead of, say, 70 percent.) Many firms also seek to recover incentives, including bonuses, marketing dollars and assistant pay. In 2019, the Corcoran Group began recouping a portion of agent commissions. Specifically, for agents receiving a higher split than the company standard, Corcoran asked them to repay the difference for the 18 months prior to their departure. Douglas Elliman claws back incentives paid within 12 months of the agent’s departure. Sometimes firms prorate the amount agents owe when they depart.

Compass’ 12-month contracts claw back the entire amount if the agent leaves within two or, sometimes, three years of receiving the incentives, according to interviews with agents and multiple contracts reviewed by TRD.

“If I sign a one-year contract, I assume it’s a one-year contract,” said @properties’ Golden. “You’re an independent contractor, but you can’t really leave.”

In a statement, Compass said its “contracts are in line with industry standards and are reflective of market norms in use at other brokerages.”

While Compass recruits agents with “above-market fee splits” for year one, it strategically renegotiates at a lower rate, according to a blog post by Alumni Ventures Group, an investor in Compass.

Agents must then choose: Stay and accept the lower split, or leave and pay back the sweeteners.

Ultimately, the onus is on the agent to read the contract, said a number of lawyers, brokerage executives and agents.

“It’s a business deal,” said Eddie Shapiro, CEO of Nest Seekers International, who added that Compass has the right to collect money it is owed.

Ravenelle, the sociologist, called the discrepancy between the contract’s term (12 months in many cases) and the length of time when Compass can demand repayment upon disassociation (up to three years) particularly troubling. “That feels like they’re trying to pull the wool over somebody’s eyes,” she said.

Not all who joined Compass were caught off guard. One New York agent said they were fully aware of the terms of the deal and knows they’ll have to repay their signing bonus, which was put toward marketing. “It is an investment,” he said. A number of other agents said they, too, studied their contracts. Many timed their exits to avoid a “disassociation repayment,” Compass’ term for how much agents owe if they depart.

After about a year at Compass, New York-based broker Chester Yow knew he wanted to leave. But to avoid being billed for incentives under his contract, he knew he had to wait until at least March 2020, when his two-year clawback period ended. He described the awkwardness of his interests being at odds with those of his clients and team members.

“You don’t know if you should pull back on your business, [or from] executing new deals that would tie you up even more,” he said. “[But] I can’t control if my clients decide to move ahead.”

Jim Ziltz, an agent in Chicago, returned to Berkshire Hathaway in March 2020 after eight months at Compass. Ziltz, who said he didn’t feel like he was getting the support he was promised, declined to disclose terms of his agreements with Compass and Berkshire.

“What I will say,” he said, “is that any cost that I incurred [for moving to Berkshire] was worth it as an investment in my business and the best interest of my clients.”

Crusader to enforcer

As Compass raised more venture capital, its relationship with its agents evolved.

In 2015, Reffkin — a Goldman Sachs alum who co-founded Compass with Ori Allon — railed against the standard agent-broker relationships. In a blog post, he vowed to reform “unfair” contractual terms that ensnared hardworking agents — his own mother included — by preventing them from switching firms. That year, Compass inserted a key-person clause in its exclusive listing agreements, allowing agents to take listings if they left the firm. That ran counter to the industry standard, in which listings belong to the firm and it’s up to the firm to release exclusives when an agent leaves.

In late 2017, SoftBank invested $450 million, bringing a growth-obsessed mentality to Compass. The brokerage compressed its three-year growth plan into one, Reffkin told Wired magazine in 2018. It stepped up recruiting and began scooping up firms wholesale. Most recently, in February, it acquired Bold New York, a 120-agent firm which specializes in new development rentals.

As Compass got more money from investors, it was able to lure agents with more generous incentives. In recent years, Compass appears to have linked the duration of clawback provisions to the size of incentives.

In one case, an agent who signed a one-year contract with a two-year clawback received a $28,500 marketing budget, $30,000 bonus and stock options. In another, an agent with a one-year deal and three-year clawback got a bonus of just over $90,000, plus a production bonus, assistant pay, limited-time split increases and a six-figure payment to cover lost commissions from their prior firm.

Other firms have also made lucrative offers to compete for agents. Coldwell Banker offered at least one agent a $200,000 cash incentive that required the agent to stay for five years or else repay it on a prorated annual basis, according to a contract reviewed by TRD.

But industry insiders say Compass’ aggressive recruiting tactics created a culture across the brokerage world in which agents shop for the highest split and biggest bonus for short-term gain. As Compass ramped up recruiting in recent years, some competitors have tightened their own clawbacks to protect themselves from losing agents.

Steve Murray, co-founder of Real Trends, said offering agents cash bonuses and other incentives is “pretty standard” fare. “But the amount of money and the speed with which Compass deployed it, I have not seen that before,” he noted.

Murray said he doesn’t necessarily see clawbacks as harmful to the industry: “It’s not an absolute bar for an agent to go to another brokerage,” he said.

Several agents who didn’t pay up before leaving Compass said they later got bills. Some bills came from Compass’ corporate headquarters in Manhattan. Others came from local law firms or collection agencies.

J. Maggio, a Chicago-based agent, said he got a bill for $20,000 nearly a year after he left Compass for @properties. He dismissed the move as a “scare tactic.”

In a lawsuit filed in January, former agent J. Gregory Maffei accused Compass of billing agents in order “to intimidate, bully, harass and annoy” them.

Read more

Len Sherman, who teaches innovation and entrepreneurship at Columbia Business School, said “sweetheart” incentive packages are often clawed back in one way or another, particularly among SoftBank-backed companies he’s studied, including DoorDash and Uber.

“I suspect agents didn’t read the fine print of their contractor agreements closely enough,” he said in an email.

However, labor experts said the fact that the industry has accepted these terms, and the contracts are legally binding, doesn’t justify the practice.

“Saying it’s a norm doesn’t mean that it’s OK,” said Erin Hatton, a sociology professor at University at Buffalo. “This is [an example of] employers coercing workers and leveraging economic power over them in a really big and fundamental way.”

Lawrence Pearson, an employment attorney at Wigdor LLP, said that the contracts brokerages make agents sign would not be allowed under New York’s labor law if agents were full-time employees. But since agents are independent contractors, “it’s more the Wild West, and [companies] can structure things the way that you want,” Pearson said.

Ravenelle said nothing good happens for a company when workers feel trapped.

“You damage your relationships with workers, you damage your relationships with customers, you damage your reputation,” she said. “And, quite frankly, how do you sleep at night?”

IPO at the end of the tunnel

For years, Compass has rallied agents behind the idea that they would benefit from a public offering.

Starting in 2018, it allowed agents who enrolled in an “agent equity program” to convert commission payments into company equity. Between 2018 and 2019, 4,200 agents participated, pouring $70 million into stock options. The firm declined to release updated figures for 2020.

Under the terms of the 2021 agent equity program, Compass is matching 10 percent of the agent’s investment, according to an internal memo.

The program requires agents to re-enroll each calendar year, and those who leave the firm before the end of the year lose any commissions invested that year.

“Just don’t leave!!! They will keep your money!!!” a former Compass agent wrote on Instagram in December. “We had 10% of OUR commission going to the equity program and when we left they said we ‘forfeited it.’”

The promise of stock was particularly resonant with agents in San Francisco, who are accustomed to dealing with tech entrepreneurs. “Those agents are definitely like, ‘OK, I’ll hold out for that payout,’” said the head of a rival firm in California. “There’s that carrot on the end of the stick: ‘I might be able to get stock shares worth $300 a share, and I’m in it for $150.’”

Given that Compass is the first major brokerage to formally offer up equity — rather than reserve stock awards for top producers — most agents are not familiar with the ins and outs of such deals.

“There’s nothing deceitful about them, but they are there to say if you get recruited away tomorrow, you’re not going to get your stock and you’re going to owe us a lot of money,” said the head of another California brokerage. “That’s a Wall Street move.”

Guy Gal, co-founder and CEO of Side, a white-label brokerage, called the agent equity program problematic.

“A good business wins on the value it creates, not the gimmicks and tricks,” he said.

Some agents who participated in the equity program said they did so enthusiastically. It was only when they decided to leave that their views changed.

“I believed in the company, and I totally drank the Kool-Aid,” said a former Compass agent in New York. The agent said they were so proud to be at Compass that they invested 5 percent of all of their commission payments into the agent equity program, totaling nearly $6,000 over two years. The agent said they didn’t realize they’d be leaving money on the table when they quit.

A team in California walked away from $45,000 in stock options when their contract was up for renewal and Compass indicated it planned to lower their split.

“It was a red or blue pill,” one team member said. “Which one [was] going to be less harmful?”

Winner takes all

Compass’ looming IPO means agent retention has become even more of a priority.

One key litmus test is coming up in California. Over an eight-month period in 2018 and 2019, Compass acquired Pacific Union International, Paragon and Alain Pinel Realtors — three top firms with 3,200 agents combined. Many of those agents’ contracts are set to expire in the next year.

“One of the things they’re going to try to convince the market is that they’ve had virtually no departures — and that will always be the case,” said Clelia Peters, president of Warburg Realty and a venture partner at Bain Capital Ventures. “It’s essential that they convince the market to justify what they’re trying to do.”

The clawbacks could alienate talented agents, particularly at a time when Compass needs to scale.

“This can work really well [for the firm] if 90 percent of the market [share] goes to Compass and that’s the only option you have,” said Gad Allon, a professor at the Wharton School who studies competition. “That’s very far from the case.”

For some agents, staying with Compass is the only reasonable option right now.

The New York agent who is on the hook for $400,000 said the prospect of such a large bill is too daunting and offered the experience as a cautionary tale.

“They know what they’re doing. It’s very calculating,” the agent said. “In hindsight, I wish I never got involved.”