The suspicion, anger and lack of trust over money can make the atmosphere at 111 Centre Street in Lower Manhattan seem a lot like divorce court. But the sparse halls and windowless hearing rooms of Housing Court are filled with the emotional energy of squabbling landlords and tenants. Landlords turn to the courts to oust troublesome tenants, nonpaying tenants, and, in some cases, low-paying tenants.

In the vast majority of Manhattan buildings, landlords bring one or two cases at any one time against renters, typically representing just a fraction of a percent of the units.

But an analysis by The Real Deal of data from the New York State Unified Court System found that for a handful of buildings, there are much higher rates of Housing Court action: buildings where as many as a third of the residents are facing legal proceedings from their landlords. Most cases are either for nonpayment, which are filed in an attempt to recover money from a tenant; or holdovers, cases which are filed to remove tenants who the landlord claims are improperly occupying an apartment.

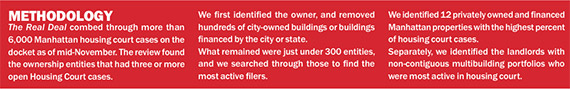

This month, for the first time ever, to find what rates represent a norm, as well as who are the most active landlords in Housing Court and why, TRD combed through more than 6,000 Manhattan Housing Court cases on the docket as of mid-November. We identified 12 privately owned and financed Manhattan properties with the highest percent of Housing Court cases, and separately, the landlords who were most active in Housing Court.

A little background: The number of Housing Court cases filed in Manhattan fell about 24 percent over the past six years, to 59,173 in 2013, the most recent figures from the New York State Unified Court System show. But the number of evictions rose to 4,525, in 2013, an increase of 13 percent from the year earlier, the city’s Department of Investigation reported. Taken together, the two statistics show that a Housing Court case filing is increasingly likely to lead to an eviction. The ratio of evictions to cases filed rose to 7.6 percent, or nearly one out of every 13 cases in 2013, from 5 percent, or one out of every 20 cases, in 2007.

Full court press

The most active buildings in TRD’s survey, as a percentage of their units, were concentrated in Upper Manhattan. However, the single most-active building as a percentage was an anomaly within this survey, both for its location, and because it is not owned by a typical landlord. The Daughters of Mary of the Immaculate Conception, an order of nuns based in New Britain, Connecticut, own and operate St. Joseph’s Immigrant Home, a 75-unit building in Hell’s Kitchen at 425 West 44th Street, between Ninth and 10th avenues. The building, with common bathrooms and kitchens, has provided low-cost housing to immigrant women for decades.

In an effort to stabilize the finances of the building, which a source said runs a deficit of about $100,000 per year, the nuns imposed an increase in the rent by $150 per room per month. That was up from a range of $375 to $475 per month. While some tenants left, and some paid the higher rate, a group of women balked at the increases and initiated a rent strike.

By mid-November, the order had filed 25 holdover cases, representing one-third of the building’s units, against the tenants in an effort to impose the higher rent. That figure rose to 27 cases last month. Since the single-room occupancy building is owned by a nonprofit religious group using it for a charity purpose, the tenants are not protected by the same laws that apply to most SRO buildings, said Joe Restuccia, co-chair of Community Board 4’s housing, health and human services committee.

The SRO-focused MFY Legal Services, along with the nonprofit Housing Conservation Coordinators and the Goddard Riverside SRO Law Project, are representing the 27 tenants. An attorney for Goddard said the order wants all of those tenants out by January 2016.

“Even with the rent increases, which more than half of the residents are paying, it will take years for my client to erase this deficit,” Andrew Wagner, an attorney representing the nuns. said in an email. Next on the list was the low-profile landlord Cyrus Management, led by members of the Hakakian family. Cyrus owns three six-story buildings at 533, 537 and 541 West 158th Street in Washington Heights, which have a total of 70 units. The landlord had 21 open cases in housing court, or 30 percent of the apartments in the buildings, as of mid-November. The company did not respond to a request for comment. Housing advocate Evan Hess of the nonprofit Northern Manhattan Improvement Corp., was not familiar with the specifics of the buildings, but observed that 30 percent seemed unusually high. “It is not common for so many cases in a building,” he said.

Economics in play

The next-most-active building in Housing Court, 148 West 141st Street, is one of six properties on the list owned by the investment firm Castellan Real Estate Partners and managed by Liberty Place Property Management. A real estate investment fund created by Massey Knakal Realty Services and RiverOak Investment is a partner is several of the Castellan buildings. At 148 West 141st Street, the owners had six open cases from among 29 apartments. However, five of those were brought against Pathways to Housing, a bankrupt nonprofit originally established to help the homeless. In Castellan’s other five buildings among the top 12, there were 30 Housing Court cases, including eight additional Pathways cases. The majority of cases involved nonpayment.

Source note: The Real Deal analysis of active Manhattan Housing Court cases from the NYS Unified Court System on Nov. 10. These landlords had 20 or more open cases in their noncontiguous and nonattached multibuilding portfolios. TRD counted privately owned and financed buildings with three or more open cases.

Last year, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced a settlement after the state’s Tenant Protection Unit investigated allegations that Castellan and Liberty Place had harassed immigrant tenants. Liberty Place COO Rick Serrapica, speaking on behalf of Castellan, said the company was operating its business carefully, following all the state’s guidelines, “and in fact we usually go further than required.”

Serrapica discussed the firms’ policy on housing court cases at length with TRD.

“As to the number of cases open at any given time, the usual reason is economics: bad economy, loss of a job, tough to find a new job, and so on,” he said. Serrapica said the firm, which tracks nonpayment cases as a percent of total units within its overall portfolio, brings an action when the tenant is two months in arrears and also after reaching out to the tenant to determine why he or she has not been paying. Overall, the ratio of units with cases in Housing Court has been falling over the past 18 months, he said, citing internal figures. Serrapica said he couldn’t say why his firm’s percentages were so much higher than others’, because he didn’t know how others were run.

“Sometimes,” he said, “you’ll find that a company has a very low case load, simply because no one is reviewing arrears.”

Massey Knakal declined to comment. The fourth-most-active building on the list was 2254 Fifth Avenue, owned by Irving Langer’s E&M Associates. The six-story walk-up in Central Harlem, between 137th and 138th streets, has 16 units. The company has three open cases in the building, all for nonpayment. Langer did not respond to a request for comment. In the ninth position was Moshe Piller’s MP Management, which had 10 open cases in the 84-unit elevator building at 1 Jacobus Place in Marble Hill, or about 12 percent. Piller did not respond to a request for comment.

Changing tactics

Holdover cases are typically used to remove tenants that are non-primary or are allegedly not covered by rent regulation. Those types of cases were popular in the boom years of 2005 through 2007, when landlords were trying to move out large numbers of tenants from complexes such as Stuyvesant Town, or from several portfolios in Queens, with the hopes of bringing in new tenants paying higher rents.

Generally, however, landlords in Manhattan have stepped back from aggressively filing holdover cases. Among the dozen buildings TRD highlighted, the vast majority of the cases filed were nonpayment cases. But there were a few exceptions. In addition to 425 West 44th Street (where all the cases were holdover cases), 11 of the 21 cases at 533-541 West 158th Street are holdovers. And two buildings, ranking 10th and 11th on the list, are in gentrifying areas of the city and had several holdover cases. In the larger building, owned by Kushner Companies, there were a total of five holdover cases brought against residents in four of the apartments at 170-174 East Second Street in the East Village.

The two adjacent buildings between Avenues A and B have a total of 43 residential units. In four of the cases (there are two cases brought against one tenant), the landlord claims the tenants are not rent-regulated, and so don’t have the right to renew their leases. The tenants maintain they are rent-regulated and have a right to remain, and the cases remain in court. The fifth case was brought against a tenant living in a “Collyers’ Mansion” condition, meaning the apartment was so cluttered as to be potentially dangerous. That tenant, following a clean-up of the apartment, has settled the case and will remain, a spokesperson for the landlord said.

In a case in the West Village, the landlord Icon Realty Management owns 56 West 11th Street, a 36-unit building between Fifth and Sixth avenues, where in November it had three holdover cases and one nonpayment case. Anthony Rodriguez, a supervising attorney at the real estate-focused law firm Kossoff PLLC, who was representing Icon, said the tenants in the holdover cases were leasing their units to others. “Each holdover proceeding was commenced based upon the fact that the tenants were not primarily residing in their apartments and were subletting the apartments without the owner’s consent,” he said in a statement to TRD. The nonpayment, he said, was a typical case and the tenant has left, but still owes back rent. Neither Kushner nor Icon had any other properties with three or more Housing Court cases within their wider portfolios, the TRD analysis found.

Most active

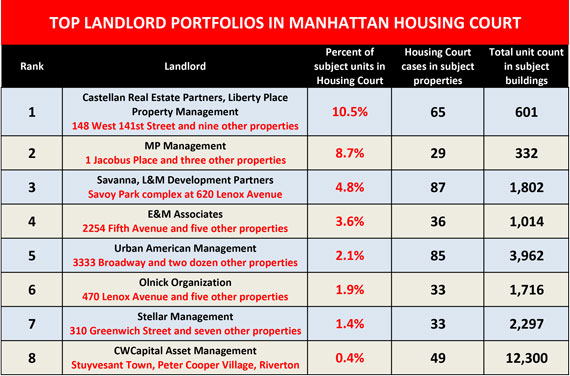

The analysis of the 6,000 cases found that within the privately owned and financed companies, there was a large range in the percentage of units in housing court. Some firms, such as Castellan, had a large number of units in court. That obviously puts pressure on revenue, because the tenant typically is not paying rent. Insiders said a 10 percent rate of units in court at a given time could be reasonable, taking into consideration the economic times, rising rental rates and the financial stability of tenants in different neighborhoods. “It does not shock me that a landlord would have 10 percent in court with a low-income population,” Edward Josephson, director of litigation at South Brooklyn Legal Services, said.

Nonetheless, very few landlords had rates that high. For example, Savanna and L&M Development Partners, which in 2012 purchased the Savoy, a 1,802-unit complex of buildings in Harlem, for $82 million, had a rate of 4.8 percent there. That mid-range number was in part because of a hold on nonpayment cases by the prior owner, Vantage Properties, which was being scrutinized by the state.

“The number of open court cases at the Savoy reflects our ongoing work to rehabilitate a distressed property and ensure compliance with rent-stabilization laws,” said a spokesperson for C&C Management, which is the management arm of L&M Development Partners. And while Langer had a rate of nearly 19 percent in the previously cited building on Fifth Avenue, among a wider group of buildings with a total of 1,014 units, he had a rate of just 3.6 percent. Also in Harlem, the Olnick Organization owns a 1,716-unit series of buildings known as Lenox Terrace, which combined had a rate of just 1.9 percent. And CWCapital Asset Management, which controls Stuyvesant Town, Peter Cooper Village and Riverton, which were all once heated battlegrounds in Housing Court, had a combined rate of approximately 0.4 percent, the survey found.

Correction: The print version of this story had the incorrect number of units at the Savoy. There are 1,802.