As Los Angeles and other major American cities grapple with the shortage of affordable housing, one major federal program is now at risk: the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC).

The expectation that Trump and Congress will cut corporate taxes is already making the tax credits worth less to investors, experts say. And that could mean more than 16,000 units of affordable housing a year won’t get built across the country.

Established by Congress in 1986, LIHTC is a dollar-for-dollar credit that allows corporations and banks to off set tax liability by investing directly in affordable housing projects, buying up a finite number of government-issued tax credits from housing developers.

By the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development’s own conservative estimates, this program helped finance more than 108,423 low-income housing units in California, most of them in the city of Los Angeles, between 2005 and 2014.

Stephanie Klasky-Gamer, CEO of nonprofit housing developer L.A. Family Housing, told TRD that LIHTC makes up the majority of financing for affordable housing development in California. Typically for a project that benefits from the program, the tax credit accounts for 60 percent of its financing, she added.

“It’s a huge critical resource for California,” she said.

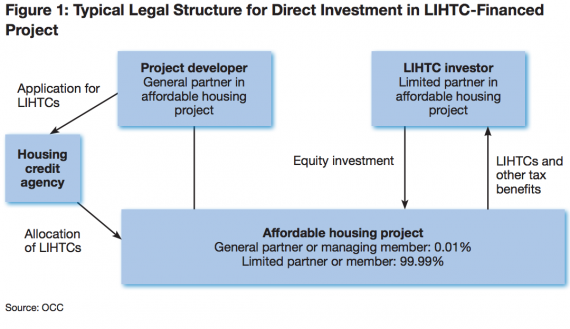

In case you’re curious, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency has a simplified flow chart that shows how LIHTC finances affordable housing:

The big problem with any system built on tax credits, of course, is that if tax rates ever drop, so does the value of the credits, making them worth much less to investors.

President Donald Trump and his Treasury Secretary nominee Steven Mnuchin are calling for corporate taxes to drop big league, from 35 percent all the way down to 15 percent. House Republicans have called for big cut too—they proposed a rate of 20 percent in June.

With Obama out and Trump in, a thorough slashing of rates seems inevitable.

In fact, all of this discussion over even the possibility of comprehensive tax reform was enough to rock the market for housing tax credits this fall, said Ben Metcalf, former HUD official and current director of the California Department of Housing and Community Development.

“Even though no legislation has even passed, the marketplace is already discounting these credits because of the expectation of corporate tax reform,” Metcalf said. The state of California is already looking at a $200 – $250 million hit to affordable project equity year-over-year, he said.

But even if the program were to be expanded, any weaker demand or value due to tax reform (or simply the discussion of) is still a big problem. Tax credits that were once trading for a dollar have dropped closer to 90 cents in some cases, and if corporate taxes drop, that could continue.

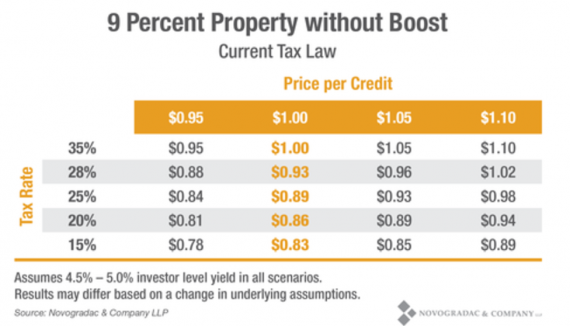

In fact, LIHTC prices slipped over three consecutive months to close out 2016, according to an analysis by Novogradac, an accounting firm. Furthermore, Novogradac estimates that prices for credits currently worth a dollar — so-called “9 percent” credits that can typically be sold to cover 70 percent of a developer’s costs in a project — could drop all the way to 83 cents per credit if the corporate tax rate is lowered to 15 percent, the way Trump and Mnuchin say they want want it to. That could lead to more than 16,000 fewer affordable housing units a year nationally.

“I frankly don’t know how they can mitigate that basic economic reality,” said Jim Parrott, a former Obama White House economic advisor and a current senior fellow at Washington’s Urban Institute.

Jolie Milstein, the director of New York State Association for Affordable Housing, is more optimistic. She says even though the value of individual credits is already dropping, demand is still high enough that simply issuing many more credits, even at lower prices, can help make up the equity gap.

“We believe there is sufficient demand,” Milstein said. “We still have a vast shortage of credit in many states like New York and California… we way exceed demand for the credit.”

Metcalf echoed that, saying the government can “put more credits into place to compensate for the fact that each individual credit is worth less.”

Stephanie Sosa, a senior associate and LIHTC underwriter for the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD), said she supports the government issuing more credits, but is more skeptical about whether that would actually make up for lagging prices in a lower tax environment.

“I’m not sure it would help projects,” Sosa said. “There would be more demand to develop more units, but investment would have to be there.”

Such a proposal to increase credits does exist on the hill. Senators Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and Maria Cantwell (D-WA) introduced a bill to expand the credits by 50 percent last spring. Many observers expect it to resurface sometime this year.

Interestingly, Trump himself once went to Congress to complain that lower tax rates were discouraging investment in low- and middle-income housing. In his 1991 testimony he said, “…frankly, by having cut the high income tax rates to 25 percent, as an example, people don’t have the incentive any more to invest. They’re saying, ‘Why should I take a chance on investing in low or moderate-income housing? I might as well just pay the tax.'”

Ben St. Clair and Cathaleen Chen contributed research to this report