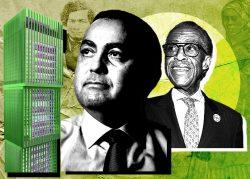

In late March, on a morning when Southern California was gripped by a freak rainstorm, developers Don Peebles and Victor MacFarlane huddled for about 15 minutes with L.A. City Councilman Kevin de León under a white canopy tent set up at the top of Downtown L.A.’s famously steep Angels Flight Railway.

The trio were awaiting a press event to announce the developers’ recently secured approvals for Angels Landing, a project that ranks among the biggest in the Western United States. Behind them two poster boards showed off the latest renderings, and a few feet away, under a larger tent, an audience of reporters, project affiliates and union workers nibbled on bagels amid the howling wind. In time de León — at the time still a mayoral candidate — stood at the podium, dressed in a dark overcoat and boots, and spoke in praise of the project’s labor agreements. Afterwards he shook a few hands and walked away.

The brief meeting was the only time the council member ever met with the developers.

“I could go see the president of the United States or the Speaker of the House of Representatives far sooner than I could see the district council member where we’re spending $1.6 billion in his district. I mean, I’ve never seen anything like it — ever,” Peebles said. “But now we understand that he has a problem — that it’s African Americans developing the project.”

Following the press conference, the two added, de León’s team contacted them to request that they take down an online post referencing his remarks — he still hadn’t decided if he would support the project.

Angels Landing, a project that includes two mixed-use buildings with hotels, apartments, open space and restaurants, is slated to rise roughly 850 feet, making it the third-tallest building in L.A. and the tallest in the country built by African American developers. Peebles and MacFarlane spoke to TRD on the heels of a legislative victory for the megaproject: Late last month, as part of a flurry of pro-housing bills https://therealdeal.com/la/2022/09/29/newsom-signs-flurry-of-housing-bills/, Calif. Gov. Gavin Newsom also signed one bill that specifically benefits Angels Landing and two other L.A. projects.

The legislation, SB 1373, extends by two years the time the Angels Landing project team, which includes Peebles’s and MacFarlane’s firms as well as Claridge Properties, a firm led by the developer Ricardo Pagan, has to complete a purchase agreement for the site. Although the L.A. City Council selected the team for the project in late 2017, a state agency — the successor to the Community Redevelopment Agency — actually still owns the land.

Under previous state law, the developers had to close a land purchase by the end of this year before local government could reclaim the land. The new law, which was authored by Sen. Sydney Kamlager, a Democrat who represents part of L.A. County, including Downtown L.A., extends the time until the end of 2024. In 2017 the developers proposed a purchase price of $50 million.

“It was pretty much an artificial deadline, but we were running out of time,” MacFarlane said of the previous law.

In recent months, while the development team was pushing for new state legislation, they had help from the City of L.A. mayor’s office, the two said. And Kamlager, who was elected in 2021 and is a member of the California Legislative Black Caucus, spearheaded the effort in Sacramento “because she understood the importance of the project,” Peebles added.

But the developers say that the current L.A. City Council — the body that holds vast influence over development projects and is now embroiled in a still-reverberating racism scandal emanating from a private conversation involving three members of its Latino caucus, including de León — never took much interest in a project that would reshape the Downtown L.A. skyline.

That included former council president Nury Martinez, the politician at the center of the scandal, which has highlighted tensions between Blacks and Latinos within City Hall.

Years ago, Peebles said, the team regularly connected with former council president Herb Wesson, who is Black and supported the project.

“This president,” Peebles continued, “refused to even meet with us, and we’re doing one of the largest development projects in the city.”

But the high-profile developers mostly blame de León, who, in the tradition of the council, wields a near monopoly on the council’s actions because the project falls in his district.

“And we were just puzzled,” Peebles said. “What is it? Is the guy anti-business? But then he’s supporting other business deals.”

After the racist audio tape leaked earlier this month — in which Martinez refers to another council member’s Black son as a “little monkey” and a fashion accessory and de León eagerly plays along — the developers said they have their answer.

“We don’t deal with racists,” MacFarlane said. “So we are not going to interface with Kevin de León, period.”

Late last week, the two also sent a letter to acting council president Mitch O’Farrell calling for de León’s resignation.

“We stress that we want to bring Angels Landing to fruition,” it read in part. “We still believe in Los Angeles … But we can no longer work with Council Member de León.

De León’s office did not immediately respond to interview requests.

It’s unclear exactly what that stance — and the still ongoing council turmoil — will mean for Angels Landing. In the wake of the scandal, Martinez resigned; de León and Gil Cedillo, another councilmember involved, have been stripped of their committee assignments but have so far resisted calls to resign. Under council rules the council cannot actually remove them from their posts.

Peebles, whose company is based in Miami but who has developed in New York and elsewhere, is particularly well acquainted with long timelines and project difficulties. One of his projects in Miami spawned a nasty dispute with a partner, and a $500 million project fund he launched in 2019 that aimed to support minority and women developers around the country has also faced big hurdles.

Angels Landing has been slow, the developers said, but the project is too big to give up on, even if five years after securing the contract the two still have relatively little to show for it except for millions in sunk costs. The team now has two more years to secure the land agreement, they pointed out, and they hope to ink the remaining paperwork, including subsidy deals, this year in order to break ground in 12 to 18 months. They’re still hoping for completion by the 2028 Olympics, although that goal “is now in jeopardy if we don’t move really quickly,” MacFarlane said.

“This project is too important not to succeed,” Peebles added. “And of course the irony is the majority of the workers and contractors will most likely be Latino-owned firms.”

Read more