For nearly four hours on Oct. 11, Santa Monica appeared headed for another forgettable Tuesday evening council meeting. From their perch around the hall’s imposing dark wooden dais, the six members present recited the Pledge of Allegiance. They watched a long presentation on Filipino American History Month, debated the merits of an outdoor holiday rink and approved a Fire Department technology contract.

But shortly after 8 p.m., Jing Yeo, the city’s soft-spoken planning manager, approached the microphone, and the mood began to shift. Before the council was the matter of whether to adopt an updated version of the city’s Housing Element, the document that by state law serves as the blueprint for its housing plans. Yeo began a technical recap of the update process. Then she revealed that Santa Monica had already blown its deadline for the update by a year.

It meant that the city was subject to penalties.

“So what happens, you know, if we do not adopt tonight?” she continued in a neutral tone. “What does it mean to be out of compliance? Some of those immediate short-term consequences we are already seeing is that the city is obligated to approve what are colloquially called ‘builder’s remedy’ projects.”

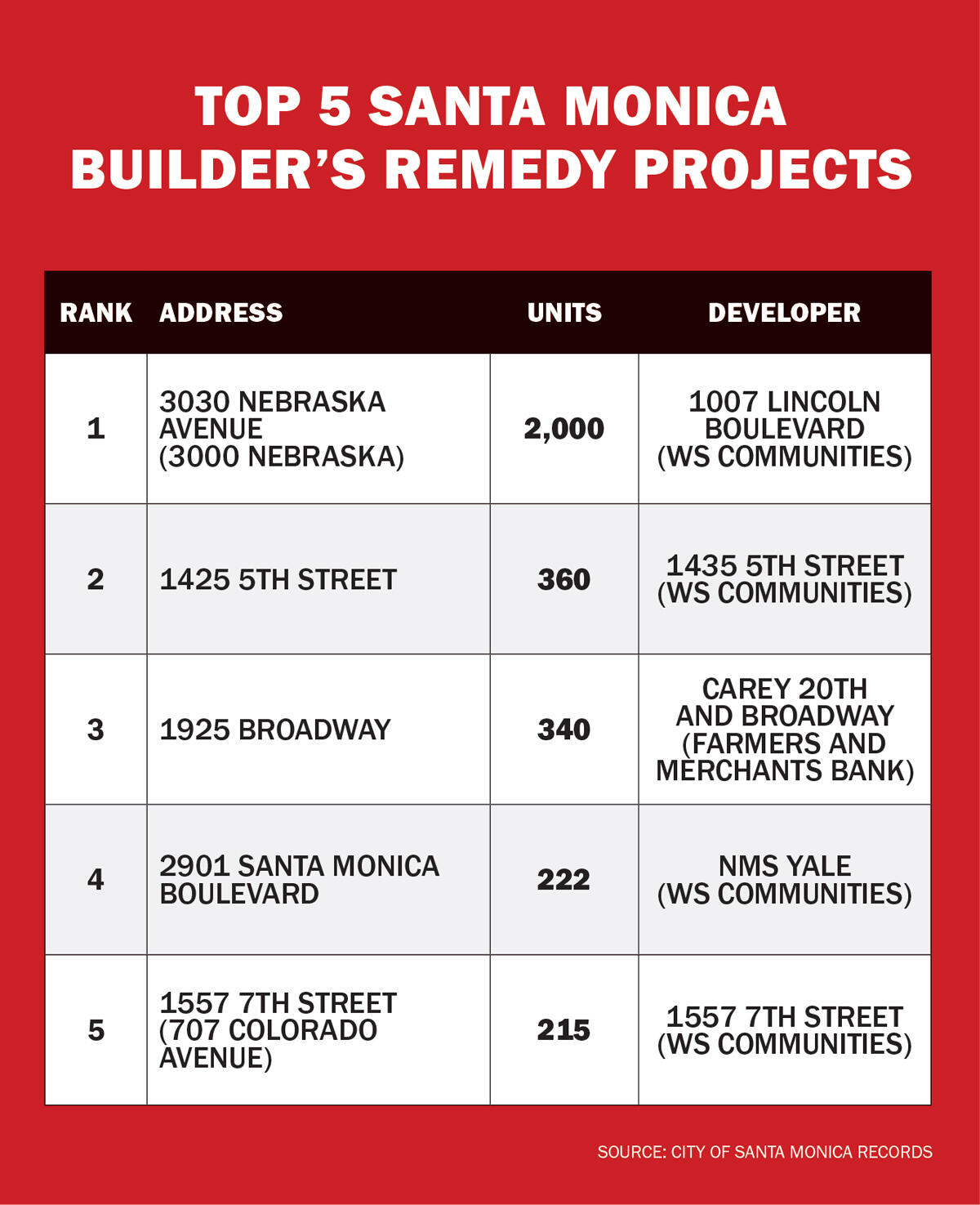

Roughly a dozen such applications had already been filed, including several in the previous days. They totaled more than 4,000 units — more than twice as many as were built in the city over the previous two decades.

“This is not theoretical,” Yeo stressed. “This is very real, and it’s happening.”

For the next hour, the council was playing catch-up. “I’m sorry to interrupt you,” council member Phil Brock cut in at one point. “Can you explain what is a builder’s remedy project?”

The members were still working through the implications of noncompliance as the council prepared to vote on the adoption itself. “In other words,” Brock said, “before HCD [the state Department of Housing and Community Development] actually stamps this and sends it back to us on Friday, anybody else could rush in tomorrow morning and Thursday morning.”

Mayor Sue Himmelrich leaned into her own microphone. “Shhhhhhhh!”

In Santa Monica, an affluent coastal city where NIMBYs have a long track record of squashing development projects, the applications hit like a bombshell.

“Don’t be ambushed and pushed around by windfall-profit developers who have no interest in the quality of our lives,” one resident pleaded to the city attorney and city manager. “We are counting on you to serve your residents!”

The proposals also set off a larger frenzy. As local and national media latched on to the story, cities across the state began examining their own Housing Element compliance. YIMBY groups prepared for a potential housing wave they hoped would undo decades of restrictive zoning. And developers sensed a gold rush.

“It’s been crazy,” Dave Rand, the affable land use attorney who filed most of the Santa Monica applications — and himself emerged as a legal quasi-celebrity, inundated with everything from hate mail to media requests — said over oysters and beer at a King’s Fish House in late October, less than three weeks after the Santa Monica meeting. “It’s been ridiculous. And I’ll be honest with you: It’s been very stressful. I haven’t been sleeping. It’s been nonstop.”

It was also just the beginning.

‘90s kid

For the past several years, California — a state beleaguered by a chronic housing shortage that’s responsible for a homelessness crisis and been blamed for everything from driving away hundreds of thousands of middle-class professionals to spreading Covid-19 among immigrants — has been awash in housing legislation.

In 2019, Gov. Gavin Newsom, elected the previous year with a promise to build 3.5 million homes, signed AB 881 and AB 68, two laws that streamlined the creation of the state’s accessory dwelling units (ADUs). Last September, Newsom signed SB 9, the controversial measure that allows homeowners to split and build on single-family lots, and SB 10, which encourages building near public transit. This year’s legislative package included efforts to transform strip malls into affordable apartments and remove infill parking requirements.

But the legal provision that emerged this fall to slap Santa Monica — and then the state — in the face has been around for decades. And nowhere does the term “builder’s remedy” appear in its text.

“As much as everyone mocked me for never having heard the term ‘builder’s remedy’ before,” Brock, the Santa Monica council member, said in a recent interview with The Real Deal, “I had never heard that term until like Oct. 8 or something.”

Almost no one in California had. “Builder’s remedy” refers to a legal maneuver that allows developers to bypass local zoning as part of a state’s effort to increase housing production, and had appeared in Massachusetts and New Jersey in the late 1960s and 1970s.

California’s provision dates back to 1990. In 1982, the state passed its first “anti-NIMBY” law, the Housing Accountability Act, which restricted cities from denying projects if they fit local zoning. Advocates of affordable housing persuaded legislators to beef up the law in 1990 by creating penalties for cities that failed to adopt state-approved Housing Elements.

One of the penalties was the builder’s remedy provision, which clarified that while cities remained out of compliance they would forfeit their authority to approve or deny projects so long as the projects met certain affordability requirements. Market-rate projects would qualify if they included at least 20 percent affordable units, local zoning be damned.

The San Francisco Chronicle called the new legislation “a powerful bill designed to bludgeon exclusive suburban communities into accepting low income housing.” NIMBY-minded city officials, including at least one Bay Area city council candidate who ran on a platform of repealing the new law, were terrified.

Instead, the provision was all but forgotten. Over the next three decades, Chris Elmendorf, a UC Davis law professor who is one of the state’s few authorities on builder’s remedy, could find only one attempted use, when a homeowner in the city of Albany cited the city’s Housing Element noncompliance in a parking dispute related to an ADU. The homeowner lost.

“So — so much for the dramatic, powerful, new builder’s remedy,” Elmendorf said in a recent virtual lecture.

The letter

This fall, Rand had been waiting for a letter from Sacramento for months. It came on Oct. 5.

“I went, ‘Oh shit,’” he said. “This is going to be a big deal.”

Now in his mid-40s, Rand has been waging an ideological battle against NIMBYism his entire adult life. In the late ‘90s, after serving as the president of UC Davis’ student body, he ran a long-shot City Council campaign on a promise to undo the college town’s notorious anti-growth policies; years later, he chose to specialize in land use law because he saw an opportunity to continue the same fight.

“But I’ve always worked for law firms where you have to be on the straight and narrow, you have to maintain good relations,” he said.

That changed in April, when, along with two partners, he opened the firm Rand Paster & Nelson. The state’s recent deluge of pro-housing legislation was rapidly changing the development landscape, and the housing crisis had simply become so bad, Rand said, that he was no longer concerned about ruffling feathers.

“Look at the homeless crisis,” he said. “Look at how many people don’t have a place to live. Look at how unaffordable this damn city is, this region.”

“Look at the homeless crisis,” he said. “Look at how many people don’t have a place to live. Look at how unaffordable this damn city is, this region.”

Rand had long been aware of builder’s remedy. But there was a nagging dilemma: What happens if, just a few weeks or months after his team files the application, the city ends up regaining compliance — and therefore its ability to negate or stall early project applications?

“I kept coming back to, ‘Guys, we’re going to file this thing, the city’s going to come into compliance, and then we’re done,’” Rand said about his conversations with clients. “They’re going to hate you, you’re going to have pissed everybody off, and you’re going to look like an ass.”

Another recent housing law, however, seemed to work in their favor. SB 330, which passed in 2019, includes an explicit right for developers to lock in advantageous zoning rules with only a preliminary application. But could a developer also use SB 330 to ensure preliminary application rights for a builder’s remedy project even if the city subsequently regains compliance?

“The answer,” the letter from an HCD official advised, “‘is yes.’”

Oct. 5 was a Wednesday, less than a week before Santa Monica City Council was scheduled to discuss its Housing Element adoption. Rand’s team filed six applications over the next two days, including the one that would prove the most controversial: a plan to build a 15-story, 2,000-unit project at 3030 Nebraska Avenue, in Santa Monica’s formerly industrial Bergamot neighborhood — the tallest building outside the city’s downtown.

Opportunity knocks

Santa Monica already knew who it was dealing with.

Neil Shekhter, a Soviet-born Jewish refugee who spent his early years in Southern California driving a cab, founded the Westside L.A. firm NMS Properties in the late 1980s. Three decades later, the firm had grown into Santa Monica’s largest apartment developer, with a portfolio of dozens of properties. It was also among its most embattled.

In 2019, the city of Santa Monica filed criminal charges alleging tenant harassment by Shekhter’s son Adam. The following year, NMS filed a federal suit challenging Santa Monica’s lease rules. Then, in 2021, the city and its rent control board named NMS in a civil suit, alleging that Shekhter’s firm was making the affordable housing crisis worse by pushing out tenants and turning some of the vacated units into illegal vacation rentals.

Adam Shekhter and the companies involved in the 2019 case agreed to pay over $100,000 as part of a diversion program that could see the charges dismissed. Both NMS’ 2020 suit and Santa Monica’s 2021 suit are ongoing.

“My advice would be never to lose faith. Always fight for what you believe,” Shekhter said in a 2020 interview with TRD. “To be a good developer, you have to be an optimist.”

Shekhter declined to comment on the recent builder’s remedy applications, but Scott Walter, the chief executive of WS Communities, the NMS spinoff behind many of the projects, characterized the filings as an act of pragmatism.

“We felt this was the best way to try and get housing built as fast as possible,” he said in mid-October. Like Rand, he emphasized the region’s “drastic housing shortfall,” and said builder’s remedy was an attempt to avoid the years it would likely take Santa Monica to change its zoning to allow for more density. Like everyone else, he was also unsure exactly what to expect next.

“It’s all new,” Walter added. “Nobody has actually done this before — these builder’s remedy projects — and I can’t speak to what the city will do.”

Walter’s team wasn’t first, however. In late July, a team led by another L.A.-area developer, Leo Pustilnikov, filed a builder’s remedy application in Santa Monica for a five-story, 45-unit project. The next month, Pustilnikov filed another builder’s remedy application for a project in Redondo Beach that ranks among the most ambitious, and controversial, in all of California: Converting a fading, 49-acre oceanfront power plant into an enormous mixed-use project with 2,300 apartments.

“It was overwhelming. It’s such a beautiful place,” Pustilnikov said of the first time he saw the site. “I don’t anticipate other 50-acre sites coming up in the South Bay anytime in our lifetimes.”

Pustilnikov (who also happens to be a Soviet-born Jewish refugee) is an audacious 37-year-old who’s already taken on major projects, including redevelopments of the Hotel Alexandria in Downtown L.A. and a Sears distribution center in Boyle Heights. He bought the power plant in 2018; this past spring, after he had already been fighting with the city for years over his plans, a conversation with a housing advocate piqued his interest in builder’s remedy.

“It wasn’t my attorneys that came up with this,” he said. “It had to be me, selling it to my attorneys that this is what we should do.”

Pustilnikov’s Redondo Beach application generated some attention in the media. But the larger development battle that has consumed the wealthy beach city for years — where the mayor was elected on a NIMBY platform and the fight over the power plant far predates Pustilnikov — meant that the attention on the developer’s unusual builder’s remedy strategy was limited.

The opposite proved true in Santa Monica. At the Oct. 11 meeting, the council ended up voting unanimously to adopt the updated Housing Element, and three days later HCD formally certified it, bringing Santa Monica back into compliance. But before the city’s builder’s remedy window closed, the number of applications had grown to 16 — including 13 from Shekhter’s and Walter’s firms, one from Pustilnikov and one all-affordable project from the investment firm Cypress Equity — for a total of over 4,500 units.

The applications divided the city. Among council members, Mayor Himmelrich, a longtime affordable-housing proponent, found a silver lining, telling a local newspaper that the projects “have more affordable housing than anything we could do.” Brock, who was elected in 2020 on a “slow growth” platform, branded WS Communities’ Bergamot project as “beyond the pale” and an “unacceptable bar for the rest of the city.”

“Am I a NIMBY?” the council member, a lifelong Democrat, added in the recent interview, responding to the same question. “I really sort of am not happy about NIMBYs or YIMBYs.”

Both groups came out in force. Within days, as the builder’s remedy story consumed Santa Monica, hundreds of residents — many affiliated with well-organized pro- and anti-development groups — had weighed in, flooding council members with calls and emails. The projects should go ahead, they urged, because they represented “a tremendous opportunity to increase desperately needed housing supply.” Or they should be stopped at all costs because they would “destroy our community” like “something out of a dystopian fever dream.”

As the fervor was still mounting, Brock and two other “slow growth” council members brought a motion urging the city to hire outside legal counsel.

Dozens of residents rallied around the idea, writing letters arguing that such a fight was the only way of “protecting the rights of our city” against “profit-motivated developers” who were attempting to utilize an untested “loophole.” Many of those same residents blamed the developers; more often, they blamed council and city planning staff for providing them the opportunity.

“They all need to be fired,” one email demanded. “NOW … every single person who worked on this.”

State of play

Under state law, California jurisdictions are required to update their Housing Elements every eight years, but the deadlines are rolling. For Nevada and Mendocino counties, near Lake Tahoe, the most recent deadline was August 2019. In rural Madera and Kings counties, in the state’s Central Valley, the next deadline won’t hit until early 2024.

Much of coastal Southern California — including all 88 cities in L.A. County and all 34 cities in Orange County — had a deadline of Oct. 15, 2021. By this fall, more than 100 hundred Southern California jurisdictions were still out of compliance. For many, Santa Monica was the warning shot.

“They’re getting 20 years of production in one year, because the City Council was not paying attention to their Housing Element,” Mike Posey, the mayor pro tem of Huntington Beach, said at an October council meeting. “It’s a travesty.”

Still, although the Santa Monica chaos propelled the previously obscure legal provision into the public domain, to date relatively few builder’s remedy projects appear to have been filed. In part, this is because the provision’s affordability requirement makes it harder to pencil projects in cities that don’t command sky-high rents.

But the Southern California list is growing. Along with Santa Monica and Redondo Beach, as of late November, YIMBY Law, a San Francisco-based nonprofit, tracked applications in the L.A. County cities of Pasadena, La Cañada Flintridge, Hawaiian Gardens and Lawndale. Pustilnikov filed more of his own in Beverly Hills and West Hollywood.

“Sending this out as an example for everyone who’s thinking about doing a BR project,” Scott Choppin, the developer behind the Hawaiian Gardens application, commented in a Twitter thread.

Unlike the 15-story Santa Monica project, the application is for a small workforce housing project in a low-profile, suburban city; Choppin also noted that it was filed by law firm Holland & Knight. Both details hint at a much broader utilization of builder’s remedy.

A final resolution for the Santa Monica projects could be months away. In late October, the city attorney floated one potential legal argument: that instead of Oct. 14, the date when HCD certified the city’s update, the city had actually regained compliance weeks earlier, when the agency indicated that Santa Monica’s draft version was on track — thereby nullifying almost all of the applications.

It was almost certainly a losing argument. And as the city continued exploring its legal options, Brock struck a different tone. While some of the proposed projects were “obviously excessive” and “out of scale for the city,” he recognized that Santa Monica was in a tough position, and was hoping for discussions with the developers. He also emphasized that the full applications hadn’t even come in yet.

“Are you going to start a battle when maybe there’s no battle needed? Maybe there’s a way to find a way to work together on this and be reasonable,” he said. “It does depend, I think, on the developer.”

“We haven’t heard from them,” Walter responded.

A much larger spectacle could be coming. The San Francisco Bay Area faces a Jan. 31 deadline, and many cities in the region, including San Jose, Palo Alto and San Francisco, are almost certain to fall out of compliance. By November, city officials were squabbling with the state. YIMBY groups were compiling resources and connecting developers with lawyers and investors. Hundreds of applications could come in on Feb. 1 — enough to change the housing landscape of the Bay Area and the entire state.

“What we’re going to have in California is this natural experiment” where many cities will effectively have no zoning in place for months, said Sonja Trauss, executive director of YIMBY Law. “So we’ll be able to see: Do we miss it? Or is it great? We think it’s going to be great.”

— Isabella Farr contributed reporting