It was the state law that was supposed to end single-family zoning and remake California’s housing industry.

But one year after the implementation of SB 9, the signature state housing law that allows homeowners to split their lots and build duplexes, “the impact … has been limited,” according to a report published Wednesday by the Terner Center, the UC Berkeley housing policy research group.

To study the law’s impact, the group analyzed 13 cities across the state where it had previously determined SB 9 usage would make the most financial sense for property owners, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego and Long Beach.

But so far — and it is still early into the SB 9 era — property owners are barely using the controversial development tool.

“We found that SB 9 activity is limited or non-existent in these 13 cities,” the researchers wrote.

The City of Los Angeles had by far the most SB 9 interest, with property owners applying to build 211 units under the law and 28 lot splits. The city had approved just 38 of the unit applications and none of the lot split applications.

That was followed by San Francisco, where property owners applied for 25 SB 9 units and four lot splits. The report found four unit applications and two lot split applications had been approved.

The application numbers amount to virtually nothing in the scheme of the cities’ overall housing pictures. In 2021, L.A. permitted nearly 20,000 new homes; that year San Diego, which received only seven SB 9 unit applications, permitted more than 5,000 new homes.

Some smaller cities, however, have seen more SB 9 activity. The Terner Center found that Saratoga, in Santa Clara County, received 15 unit applications a year after it permitted 71 total housing units. And Danville, a city of some 40,000 people in Contra Costa County, received 20 lot split applications.

The relatively high usage in those two cities, the researchers concluded, likely stems from their large lot sizes and high home prices, which makes it easier and more financially appealing for property owners to split and build.

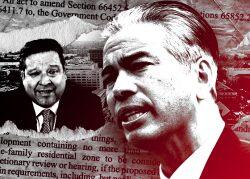

Before it was passed in 2021, SB 9 ranked among the most controversial housing laws in California’s history, as opponents spread paranoia about the looming death of neighborhood character and supporters celebrated it as a highly symbolic move toward equity and progress.

But a closer look revealed that its effect was always likely to be more incremental. Before it passed, the law was watered down to prevent the involvement of professional developers and real estate investors, while a 2021 Terner Center analysis also estimated that, while it could make the production of 700,000 new homes financially feasible, the actual number built would likely be nowhere near that figure. All along, the law was intended as a measure to promote “invisible density.”

Nevertheless, before and after it was implemented many local governments have vehemently opposed it, adding to a larger battle over housing policy between the state and many cities.

Read more