Last year, Ilan Kenig needed a $100 million credit line. His multifamily development company, FMB Development, was bleeding cash and needed money to get multiple projects off the ground.

Kenig looked to an unlikely partner: Rabbi Yoshiyahu Yosef Pinto, once an adviser to high-profile New York real estate players, then a convict, and now Morocco’s chief rabbinical judge.

Over the course of four years, Pinto brought in three partners — Isaac Croitoru, Yossi Zaga and Moises Gilinski — who took partial stakes in the company. Croitoru pumped more than $100 million into FMB, to help buy out previous lenders and investors.

When Kenig needed more cash for construction, the four investors promised it would come.

“Don’t worry the money is available, no worries, money is coming very soon,” Rabbi Pinto allegedly told Kenig, according to filings with L.A. Superior Court.

But the $100 million never came.

This month, Kenig sued Pinto, Zaga, Croitoru and Gilinski. He claimed that the four men swindled him into handing over control of his company, spent millions of company dollars and made empty promises of future cash.

Kenig also alleges that Pinto funneled about $2.1 million from FMB entities to his nonprofit, Mosdot Shuva, and more without receipts.

Fateful meeting in Marrakech

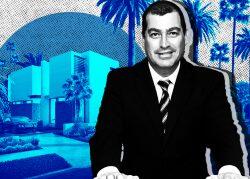

Ilan Kenig built FMB the way many form real estate companies: with a mix of equity partners, traditional debt and more expensive mezzanine loans.

Kenig started the company in 2014 and spent five years buying more than 60 properties across the Los Angeles area, from Pacific Palisades to Koreatown. He slated some for multifamily, others for spec home development.

Construction seems to have started on only a handful of projects, including a 28-unit apartment complex in North Hollywood, where the structure is complete but the units have not been listed. When Kenig needed the nine-figure credit line, he found his answer in an unlikely place: Morocco.

In 2019, while visiting Marrakech, Kenig met Rabbi Pinto, the country’s newly appointed chief rabbi.

Pinto was a celebrity of sorts. By the late 2000s, the rabbi was a “spiritual adviser” to the stars, including Lebron James, and to many of New York’s prominent real estate brokers and developers.

“He’s going to hook you up with a lot of people,” an Israeli broker told The Real Deal in 2008.

But by 2012, Pinto was the subject of a money-laundering probe in Israel. Federal investigators in the U.S. also had their sights on the rabbi and were speaking to investors about claims that money was disappearing from real estate developments tied to Pinto.

In 2014, Pinto was indicted in Israel, where he had allegedly tried to bribe a police officer for information on the money laundering investigation. He served a year in prison. Two years after his release, in 2019, he was appointed as Morocco’s top rabbi.

Kenig said in his lawsuit that he was “deeply influenced” by Pinto and became a follower, feeling “honored to be part of Rabbi Pinto’s inner circle.”

“The Blessed Group”

Two members of that coveted circle were Zaga, a long-time associate of Pinto’s, and known for dabbling in real estate.

The other was Gilinski, allegedly worth hundreds of millions of dollars thanks to cryptocurrency investments and a food manufacturing and export business in Colombia.

In January 2020, Kenig said he joined the three men for Shabbat dinner at Pinto’s house in Marrakech. There, Pinto shared his proposal: Zaga and Gilinski would help fund FMB’s expansion and buy out current investors.

While reciting the traditional blessing over bread, Pinto broke the bread into three parts — to Gilinski, Zaga and Kenig — to symbolize dividing up FMB. Kenig formally transferred the interests in FMB accordingly, “following Pinto’s directives,” Kenig said in his complaint.

“This significant interest was given without requiring any capital investment from them and was provided by Ilan in FMB solely based on the instructions of Rabbi Pinto,” he added.

The three even started a group chat — “The Blessed Group.”

“My company”

After the restructuring, Pinto allegedly became more involved in FMB’s day-to-day operation, visiting projects, offering advice and suggesting valuations on projects. Pinto, Gilinski and Zaga had also decided to halt all property sales.

Pinto started calling FMB “my company,” Kenig alleged in his suit, leading Kenig to believe that Pinto was behind Zaga’s one-third interest in FMB. Kenig also said that Pinto asked the company to pay for personal expenses in L.A. including private jet travel, a house rental in Beverly Hills and family vacation activities.

Pinto enlisted another investor, Croitoru, to pump money into FMB properties. From 2019 to 2023, Croitoru poured $109 million into FMB to buy out investors and replace mezzanine financing.

But Kenig said that FMB’s development never actually benefited from that. Instead, the money was allegedly diverted elsewhere.

“Every time Gilinski or Croitoru made a wire to the FMB Entities,” Kenig claimed, Pinto’s assistant or Zaga “would immediately demand a corresponding payment be made” from FMB to Mosdot Shuva, the nonprofit.

Pinto’s nonprofit has been scrutinized over the years. In 2011, its representatives were unable to provide details to the Forward on the management and finances of its Manhattan branch, and the rabbi reportedly claimed no knowledge of its budget. A separate report uncovered expenditures of hundreds of thousands of dollars on luxury Hamptons rentals, jewelry, first-class flights and men’s suits.

In New York, the organization’s synagogue building at 122 East 58th Street has gone through a series of foreclosure attempts before being refinanced. In 2010, the rabbi’s $6.5 million townhouse (also owned by the nonprofit) faced foreclosure at one point. Another Pinto project, a synagogue in the condominium at 240 Riverside Boulevard, also fell through.

Despite the trail of mishaps, Pinto built himself a reputation as an adviser to business people and specifically to real estate players, so Kenig trusted him.

In his suit, Kenig alleges that in 2021, Pinto approached him for help preventing foreclosure at his Manhattan building; Kenig agreed to sign as a personal guarantor for a refinancing loan of approximately $24 million from Parke Bank.

But pressure on Kenig’s development projects was mounting, and he needed the $100 million credit line to prevent defaults. The four defendants continually told Kenig not to worry, that Croitoru would provide the line of credit. In exchange, Kenig agreed to hand over a 25 percent equity stake in FMB.

“Everything is good, the money is available, everything will be fine, and the money should be received by the company in a matter of days,” Pinto allegedly told Kenig in an October meeting in New York. The rabbi advised the FMB principal that he should keep all his properties and assure lenders that funding was en route.

But the next month, at a meeting in New York, the defendants’ lawyers sent Kenig a restructuring agreement “designed to take away” Kenig’s interests and decision-making. At that point, Kenig concluded he was dealing with a “corrupted coalition.”

Read more

“Burned to ashes”

In his suit, Kenig alleges a “hostile takeover” — a scheme to push his business into a cash crunch and take over his interests in FMB entities. Pinto, he alleges, intended “to use FMB funds for payment of the Mosdot Building” and for his “personal gain.”

Kenig claims that he is stuck with $240 million in loans with personal guarantees. He has filed for bankruptcy on at least six FMB multifamily projects in L.A., according to court filings.

Kenig is also facing a number of lawsuits from joint venture partners and lenders, claiming FMB failed to complete projects on time, defaulted on tax obligations and loans.

“Almost all” of FMB’s properties are in default, he said in his complaint.

Kenig, in his suit, blames the four men for leaving him with “a bad reputation, bad relationships with lenders, investors and suppliers that will prohibit him from doing any business whatsoever.”

In his words, they have burned a “multi-million dollar empire to ashes.”

Pinto and Gilinski have not responded to request for comment. Zaga and Croitoru could not be reached. Kenig has not responded to multiple requests for comment.