Over the past handful of months, the tech titans of Silicon Valley have launched an all-out blitz on commercial space in Los Angeles.

In October, Hudson Pacific Properties signed a deal with Netflix for the streaming giant to take the entire 13-story Epic building in Hollywood while it was still under construction. A month later, Kilroy Realty leased the entire office component of its nearby Academy on Vine project to Netflix, while it too was under construction.

In January, Tishman Speyer closed a deal for Facebook to occupy 260,000 square feet at the Brickyard campus in Playa Vista — more than twice what the social network said it would lease five months earlier. Only days later, Apple struck, reportedly engaging in talks to grab the remaining 150,000 square feet at One Culver in Culver City.

And in the biggest deal of the recent wave, Hudson signed up Google for all 584,000 square feet of the Westside Pavilion mall in West L.A., capping a four-month period in which Google increased its space in Los Angeles nearly sevenfold.

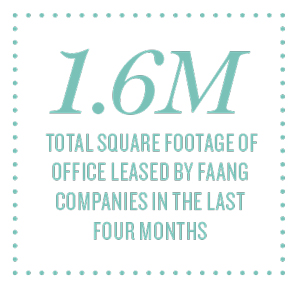

Just those five deals, part of a late-season acceleration of office leasing by major tech firms, added at least 1.6 million square feet to their growing L.A. portfolios.

“The leasing activity by these tech and media companies over the past 60 days has been unprecedented,” said Owen Fileti, senior executive director with L.A. Realty Partners. “This level of positive office space absorption is extraordinary, and it propels market expansion.”

The spate of transactions is part of a scramble for office space in L.A. that has been underway among Silicon Valley companies with growing ambitions — and matching deep pockets — to expand their operations. Leading the push are the so-called FAANG companies: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google. They are locking up many of the largest and highest-quality spaces in Hollywood, Culver City and Playa Vista, driving up rents while helping to fuel residential development around their facilities.

The run on commercial space has been a boon for major developers like Hudson, Kilroy and Hackman Capital Partners. And yet the recent push also comes at a disquieting time in the tech industry that has even some beneficiaries — as well as observers — of the L.A. boom wondering whether the mad dash for space is a little too good to be true.

The run on commercial space has been a boon for major developers like Hudson, Kilroy and Hackman Capital Partners. And yet the recent push also comes at a disquieting time in the tech industry that has even some beneficiaries — as well as observers — of the L.A. boom wondering whether the mad dash for space is a little too good to be true.

“I wake up every morning thinking this is the day that everything falls apart,” said Michael Hackman, the CEO and founder of Hackman Capital. “With all these people running around creating content, at what point do you reach saturation in the market?”

For Hackman, the ghosts of the first dot-com crash — when failing startup firms like Pets.com abandoned dozens of commercial spaces in the Bay Area — are real. “We are roughly around the same time frame in the cycle today as that downturn,” he said.

Christopher Rising, the president of Rising Realty Partners, another L.A.-based developer, agreed that the tech firms may be moving too quickly in their rush to scoop up available properties. “There is going to be a hiccup at some point,” Rising said. “I have no doubt that someone is going to stub their toe … and get overly optimistic about what their needs are.”

The nervousness reflects a growing tension in the commercial developers’ burgeoning relationships with the Silicon Valley firms. In many cases, the recent melding of tech and content that led FAANG and its ilk to set up shop in L.A. caught developers by surprise.

“If you had asked me five years ago would you see Apple and Amazon in Hollywood or L.A., I would have said, ‘Well, maybe a small sales office,’” said Robert Paratte, the executive vice president for leasing and business development at Kilroy.

Lately, seesawing valuations of major tech stocks have driven down the Nasdaq, fueled by a trade war with China and concern on Wall Street about the hyper-competition for the streaming video content market being led by Netflix. That’s not to mention potential regulatory concerns around Facebook and Google due to their expanding reach and ongoing privacy issues.

All of that has some commercial players wondering whether the sudden decline of Snap Inc., which led the firm to abruptly pull out of all of its office space in Venice Beach early last year, was more than a fluke. The L.A.-based tech firm exited 14 properties in one week and moved to Santa Monica. Only about 20 percent of that space has since been subleased.

“I worry that there is one company, like Snap, or a couple of companies, that just don’t make it,” Hackman said. “Then some of the dollars that are going into tech start to retrench, which creates more vacancy that didn’t exist before, and it starts to soften the market a little bit.”

Defensive moves

For now, the L.A. market has the exact opposite problem — too little space for the fast-growing demand.

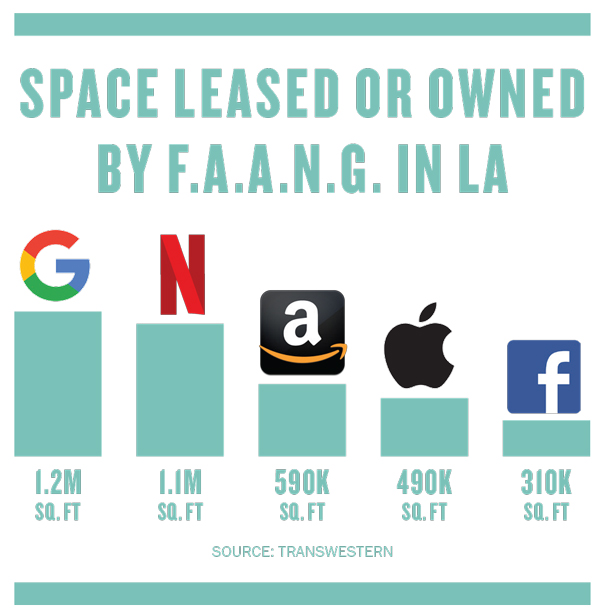

Since 2001, the FAANG firms have locked up more than 3.6 million square feet of prime office space in Los Angeles — most of that in the past five years. Including the Westside Pavilion, Google has secured the most, with 1.2 million square feet. Netflix has 1.1 million square feet, Amazon’s got 590,000 for Amazon Studios, Apple has 490,000, and Facebook has inked 310,000, according to Michael Soto, the head of research for Southern California at Transwestern.

But that may not be enough new construction to satisfy the tech firms’ growth ambitions in L.A., said Carl Muhlstein, an international director at JLL. He believes the area is heading toward a shortage of available office space. “The development community didn’t realize there would be 4 to 5 million feet of active tenant requirements through 2020,” he said.

Rising said that the talk among developers is that up to five companies in the FAANG and legacy entertainment orbit are still hunting for spaces of 300,000 square feet or more on the Westside — but only two or three options remain. One of those had been the Westside Pavilion, which he said Google took in part to be closer to Hollywood and the major entertainment studios.

The tech firms have been making “defensive moves,” locking up space they won’t occupy for another few years to box out competitors, brokers said. Netflix, for instance, has secured 683,000 square feet at two properties that won’t be available until 2020. Google scooped up all of the Westside Pavilion, but brokers indicated that the tech firm only plans to initially use a little over half the space.

The tech firms have been making “defensive moves,” locking up space they won’t occupy for another few years to box out competitors, brokers said. Netflix, for instance, has secured 683,000 square feet at two properties that won’t be available until 2020. Google scooped up all of the Westside Pavilion, but brokers indicated that the tech firm only plans to initially use a little over half the space.

Tenants are pre-leasing spec office spaces in a way that is unusual for L.A., brokers said. That has been especially true in Culver City, Hollywood and Playa Vista, the spots the tech firms are most focused on.

Developments that three years ago were 10 percent pre-leased before construction are now 30 to 50 percent pre-leased, “and even higher in Hollywood,” Fileti said.

FAANG effects

The neighborhoods where FAANG firms have moved in have seen soaring office rents. From 2013 to 2018, average rents rose by 106 percent in Playa Vista, to $5.59 per square foot a month; 66 percent in Culver City, to $4.35; and 35 percent in Hollywood, to $4.53, according to Soto at Transwestern. Santa Monica, one of L.A.’s original tech hubs, has seen its office rents grow by 49 percent to $6.06 in that five-year period, Soto said.

The vacancy rate in Hollywood has dropped to among the lowest levels in the city. In the fourth quarter, Hollywood had a 7.1 percent total office vacancy rate, compared to about 16 percent in Culver City and 17.7 percent in Playa Vista, according to Transwestern. The entire L.A. office market averaged a little more than 15 percent.

The moves are helping to spruce up formerly blighted parts of Hollywood in particular and make them more popular for millennials to work and live in. Residential rents have outpaced other areas of the city, rising by 18 percent for one-bedrooms in Hollywood over the past three years and nearly 13 percent in West Hollywood, according to surveys by Zumper, the apartment rental service.

Netflix’s arrival in Hollywood in particular coincided with a surge of infill residential development and apartment construction. More than 3,500 rental units have been constructed over the past five years, a more than threefold increase from the 1,116 units that were built from 2008 to 2013, according to data provided by Soto.

“Hollywood had block after block of surface parking lots and underdeveloped land, which today has been developed into thousands and thousands of apartments,” Muhlstein said.

BJ Turner, CEO of Dunleer Group — a Beverly Hills firm that develops low-rise apartment complexes with 25 to 70 units — has built a strategy around catering to young tech workers in and around Playa Vista, Culver City and Hollywood. Turner said Dunleer’s total apartment units have grown by two and a half times over the past three years.

Where the tech firms chose to settle in the city was no arbitrary decision. They have strategically selected neighborhoods like Hollywood and Culver City to expand their L.A. footprints not only because of the access to Hollywood industry players but also because of relatively efficient entitlement regimes.

Santa Monica, which has a diverse tech economy that includes offices of major firms like Oracle and a number of startups, has not been as successful at attracting the FAANG firms. The city’s notoriously difficult entitlement process has severely limited new office construction. It takes an average of two years longer for commercial buildings to be entitled there than in Hollywood, developers said. There is also the issue of its traffic patterns and its distance from Hollywood studios.

In January 2019, Tishman Speyer closed a deal for Facebook to occupy 260,000 square feet at the Brickyard campus in Playa Vista.

For those reasons, “Hollywood is the new Santa Monica,” Paratte said.

The creative office space equation

The properties the tech giants are leasing have a lot in common. And that’s by design.

The structures have to be new, or like new, to lure the FAANG companies. “We are not dealing with second-gen space here,” Muhlstein said. “We start out with a shell.”

Developers say they have taken pains to respect the historical elements of sites like Columbia Square and Culver Studios. At the latter, Hackman said, his firm physically picked up four storied bungalows — where Steven Spielberg stayed during the making of “E.T.” and Alfred Hitchcock had an office — and moved them as is from the back to the front of the property to create a “historical area.”

The developers have also overhauled and added to their properties to fit the creative-office trend. Much of the design has been dictated by the ways in which the tech firms have configured their spaces in Silicon Valley. That means shying away from high-rises in favor of lower, more intimate architecture with lots of floor space.

“When you go vertical you have to use elevators, and by using elevators you are separating people,” Paratte said. Tech company workers “prefer to work in teams.”

New media companies also want workers to live in walkable urban environments, Hackman said. Amazon representatives emphasized to him that they wanted their employees to integrate within their communities.

Traffic has been a major motivator in the moves to Hollywood and Culver City in particular. Developers have tried to cater to younger tech workers’ preference to drive less and to live closer to work or public transit.

The design of Icon, which was built as a fortress behind studio gates, was resulting in a morning Uber traffic jam for Netflix workers. So in discussions with the streamer over expanding at Academy on Vine, which is built more like a campus, JLL showed Netflix representatives “how our turnabouts and multiple access points would be advantageous,” Muhlstein said. Academy will also offer nearby access to the Red Line train.

The design of Icon, which was built as a fortress behind studio gates, was resulting in a morning Uber traffic jam for Netflix workers. So in discussions with the streamer over expanding at Academy on Vine, which is built more like a campus, JLL showed Netflix representatives “how our turnabouts and multiple access points would be advantageous,” Muhlstein said. Academy will also offer nearby access to the Red Line train.

To target tech workers, Dunleer has shrunk unit sizes, installed smart home technology, offered shorter-term leases of six and nine months and limited parking lot sizes “because a lot of these folks are using Birds or Uber; they are not necessarily tethered to a car.”

To compete in the FAANG world, commercial brokers in L.A. have had to learn to understand the leasing tendencies of the tech clients. Fileti said he studies their real estate usage in the Bay Area and elsewhere, looking for “correlations” and applying “pattern recognition” in the same way venture capitalists research investment opportunities.

The big bet

While most of the leases the tech firms are signing are long-term — ranging from 10 to 15 years — developers are betting heavily on them sticking around L.A even longer.

They are orienting more and more of their space to tech clients.

Hudson told investors in its 2018 filings that its two largest tenants were now Google and Netflix, which together accounted for 10 percent of the annualized base rent generated by its office properties at the end of 2017. That percentage will likely rise with Google’s recent lease of the Westside Pavilion. Hudson declined to be interviewed.

Soto said that the biggest threats to FAANG’s space grab are how the companies’ financial performance could affect their office space decisions, as well as the recent megamergers that are looming over the entire entertainment industry. Disney’s purchase of Fox and AT&T’s takeover of Time Warner have created anxiety about potential consolidation of property and staffing that could lead companies to ease back on their space requirements, he said.

Google is sitting on land around the Spruce Goose that could yield another 900,000 square feet of buildable space

Industry veterans like Paratte still recall vividly the fallout from the dot-com collapse. After the crash in late 2000, commercial vacancy rates in San Francisco had risen to 10 percent, including space for sublets, by the summer of 2001, according to figures from Cushman & Wakefield reported at the time. In 1999, during the heart of the boom, commercial vacancies had fallen to record lows of under 1 percent in some San Francisco neighborhoods, the New York Times reported.

Yet while those memories are chilling, back then many tech companies were living on their image. They often took space without having enough employees to fill it. “You had people sending proposals for full buildings, and the company hadn’t even completed its first round of Series A funding,” said Paratte, who at the time was a partner with developer William Wilson & Associates near San Francisco.

Many of the companies that wound up abandoning large spaces in San Francisco were far less established and well-capitalized than the FAANG firms of today, which, in the case of Google and Apple in particular, are sitting on hundreds of billions of dollars of cash.

“The dot-com era was a more diverse, rapid growth startup subset of companies,” Fileti said. “It was not nearly as concentrated of a list” as the major tech players moving into L.A.

And the FAANG firms are not alone in their quest for prime L.A. office space. A slew of other well-capitalized firms from the burgeoning video game industry are also in the mix, as well as virtual reality companies.

These days, the commercial industry is more preoccupied with a different question: What happens when the space runs out?

Rising said he believes the tech firms will increasingly be forced to move farther east, toward Downtown. “Hollywood is full, Culver City is full,” he said. “You are going to have to have someone go under for Hollywood to have some real vacancy.”

Or the media firms could venture farther south. Hackman Capital recently acquired a 30-acre property at 888 Douglas Boulevard in El Segundo, a former Northrop Grumman aircraft manufacturing facility. Hackman said he is readying a 380,000-square-foot building there for a media content client. “We have already had a number of media companies take a look at it,” he said.

But Rising and others see a southern push by the tech and entertainment companies as less likely, because of the complicated traffic patterns and long distance to Hollywood and the studios.

Building something from the ground up is unrealistic given the three-to-five-year entitlement process on the Westside. Google is sitting on 12 acres of land around the Spruce Goose hangar in Playa Vista it bought in 2014 that could yield another 900,000 square feet of buildable space, brokers said. But the tech giant has yet to put in motion plans to develop the property.

Hackman prepares for the future

For now, despite his concerns, Hackman is preparing for a future in which media production continues to thrive in the newly revived areas of the city.

The 62-year-old spent much of the holiday season camped in a midsized conference room at his West L.A. offices, working on details of the biggest deal of his 33-year career at the company: CBS Television City.

Hackman made a career of buying up and reselling troubled industrial properties around the world. Then a little over a decade ago he embarked on an urban infill strategy in Culver City to acquire and develop higher-quality commercial spaces, especially those with “high barriers to entry” in their entitlement processes.

Hackman has been investing heavily in building relationships with Apple and Amazon. He helped set up Apple’s Beats at a handful of buildings in Culver City and Amazon’s nascent Amazon Studios operation in the historic 14-acre Culver Studios, built in 1918. Before starting construction there, Hackman worked out a deal to purchase a neighboring property, Culver Steps, from Hudson Pacific, and then combined the properties for Amazon for a total of about 600,000 square feet.

Then, in December, Hackman agreed to purchase the 25-acre CBS Television City campus in Hollywood for $750 million. Hackman said the developer intends to operate the 780,000-square-foot studio, built in 1952, long-term.

“This is an ideal location for one of these larger content-creating companies to come in and make it their home and grow the capabilities at the site,” he said.

Hackman said he expects a big media tenant to eventually end up with the space. But for now, it will have to wait.

Along a hallway at Hackman Capital, he showed off rough schematics for possible plans for the property, including one scenario where the number of stages would be expanded, and another where multifamily housing would be added.

“Television was put on the map through this studio,” he said. “We are studying what needs to be done there to make it competitive for the next 50 to 75 years in this new and ever-evolving media content world.”