Working behind the scenes of almost every development project — both large and small — in the city of Los Angeles, there is one constant: the lobbyist.

Call them the hired guns developers need to guide them through L.A.’s archaic zoning code, to act as go-betweens with community groups and bend the ears of local Council City members, who have near-complete sway over what gets built (and what never sees the light of day) in their districts.

Developers — who have billions of dollars on the line with their high-stakes projects — clearly recognize how indispensable these dealmakers are. That is evidenced by the tens of millions of dollars a year they pay them to win special zoning variances and cut through red tape to get projects green-lit.

Vanessa Delgado, managing partner at affordable housing developer Azure Development, said that “there are almost no projects” her firm would pursue without a lobbyist and team of consultants.

The company, for example, tapped the law firm Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton to secure land-use approvals needed for a 44-unit project east of Downtown L.A., in Boyle Heights. Earlier this year, Azure secured the approvals it needed and is now scheduled to break ground next month.

“Our projects already take up to three years, but the difference can be a year if you don’t have someone correctly navigating the system,” said Delgado, noting that a missed deadline can be costly. “That’s why I hire a lobbyist.”

And she is not the only one.

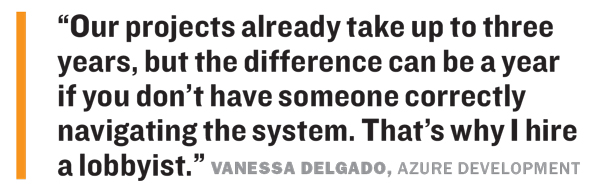

Last year, lobbying firms raked in $65.6 million in L.A. And that’s not including adjoining municipalities like Beverly Hills, Santa Monica and Inglewood.

While that figure includes cash from all industries, the majority of it came from real estate firms, according to an analysis by The Real Deal of data provided by L.A.’s City Ethics Commission.

Arnie Berghoff, a long-time L.A. lobbyist, put it simply: “We can save developers a lot of heartache and money.” (Berghoff’s eponymous three-person firm counts controversial home-sharing giant Airbnb and the multinational software company Oracle as clients.)

Arnie Berghoff, a long-time L.A. lobbyist, put it simply: “We can save developers a lot of heartache and money.” (Berghoff’s eponymous three-person firm counts controversial home-sharing giant Airbnb and the multinational software company Oracle as clients.)

He added: “Our buildings and planning departments are good, but they’re overwhelmed, and one of the jobs of the lobbyist is to get it further toward the head of the line. Usually that happens if there’s a call from an elected official who says, ‘We need this in my district, and I’d appreciate if you could expedite it.”

At the end of 2018, Berghoff — who is also representing Lightstone Group in its Fig + Pico megaproject in DTLA — was one of 451 individuals at 135 firms registered as lobbyists with the Ethics Commission. That includes land-use attorneys, consultants and others who qualify as lobbyists under the commission’s definition.

But the entire lobbying industry in L.A. has been in the spotlight since late last year. That’s when the news broke that the FBI was investigating City Council member José Huizar for allegedly accepting donations to his pet charities and his wife’s Council campaign from developers in exchange for backing their projects.

As part of that case, the FBI subpoenaed prominent lobbyist Morrie Goldman, who was allegedly involved in those donations.

In response to the Huizar scandal, the Council is developing an ordinance that would ban developers from making donations to elected officials who are voting on their projects. That ordinance is expected to come to a full Council vote this fall.

Still, sources say that even if it passes it won’t change the core function of real estate lobbyists in L.A.

And most in the industry are just going about their business — continuing to solidify their connections.

“We deal with the same audience over and over again, so you can’t help but build relationships with people,” said Dave Rand, a land-use attorney and a partner at Armbruster Goldsmith & Delvac.

“We’re lawyers first, but we absolutely have relationships and function as lobbyists,” said Rand, who has worked for development and investment firms LaTerra Development and Bolour Associates.

One top lobbyist, who asked to remain anonymous, said the industry trades on its credibility.

“You have to be credible. I learned pretty early on that you’ve got to be honest,” the lobbyist said. “I’ve fired clients because they’ve lied to me. I have to maintain my credibility or there’s no reason for someone to take my word.”

Part of that credibility, sources say, stems from extracting community concessions from developers, which can make a project more politically feasible for a local elected official to support.

But Glenn Gritzner — a partner at the public strategies firm Mercury Public Affairs — said some developers put too much stock in lobbyists’ connections.

“There’s a misnomer that ‘Oh, [this lobbyist] has a good relationship with the Council member and if we hire him the Council member will do what he wants — it doesn’t work like that,” he said. “You still have to make your case.”

Swimming in lobbyists

Because the L.A. metro area is so vast, the team on every development — including the lobbyists who are tapped — often boils down to the project’s location.

“The person you hire in Long Beach is not the same person you hire in Santa Monica,” said Jeff McConnell, a partner at Englander Knabe and Allen, a strategic communications firm that has specialities in government affairs and other areas. That, of course, is because different lobbying firms have connections with different elected officials and experience with different types of projects.

Nonetheless, sources told TRD, despite the fact that L.A. is swimming in lobbyists, just a handful of very well-established firms tend to get the bulk of the work. And the numbers bear that out: The top 10 firms raked in half of the $65.6 million spent last year on lobbying, according to TRD’s analysis.

Counterintuitively, the real estate lobbying world in L.A. is not considered cutthroat. While developers almost always interview multiple firms before putting anyone on retainer, the industry of so-called influencers is clubby. And sources say there’s more than enough work to go around.

DTLA alone has 3 million square feet of office space under construction and another 3.2 million proposed, according to the Downtown L.A. Business Improvement District’s first-quarter market report. In addition, developers are building more than 5,200 residential units in L.A.’s urban core and have proposed nearly 32,600 more.

In addition to Fig + Pico, that includes Greenland USA’s $1 billion Metropolis megaproject, which will ultimately have four towers with 1,500 residential units and a 350-key hotel.

“We can’t handle all the businesses,” said Berghoff, who hosts an annual fundraiser where mayors, Council members and law enforcement officials have all been roasted in the name of charity. “I’ll call to congratulate [another firm if it lands a new client].”

Not only that, but it’s not unheard of to turn away a client — especially for the more established lobbyists. “You spend a lot of time with developers, and some are more difficult, shall we say, to work with than others,” Berghoff said. “We all talk about it. We all have a no-assholes rule.”

Rand said he has one exception: The less-than-genteel developers he worked with early in his career who eventually became his friends.

“Through the years I built a reputation where I don’t have to take on new assholes,” he said. “The old assholes are grandfathered in.”

Below is a rundown of some of the biggest and most influential lobbyists — and law firms that are also registered as lobbyists — representing real estate players in L.A.

DLA Piper

$6.6 million in 2018

The London-based global law firm was paid $6.6 million for its L.A. lobbying in 2018 — more than any other firm registered with the city, according to Ethics Commission data. The firm boosted its L.A. presence in 2017 when it merged with Liner LLP, adding 60 attorneys.

And nearly all of the DLA’s L.A. lobbying clients last year were from the real estate world, according to TRD’s review. The firm’s 10 registered lobbyists counted Champion Real Estate Company, Greenland USA and Jamison Services as clients.

Jamison hired DLA to work on multifamily developments that it’s planning in Westlake and Venice, while Greenland tapped it to represent the Metropolis.

Englander Knabe & Allen and Three6ixty

$4.5 million in 2018

The communications firm EKA launched in 2005, but founder Harvey Englander has been active in PR and lobbying for four decades and has a reputation as one of the most connected and effective players in L.A.

Last fall, the firm merged with the planning and land-use consultancy Three6ixty. While the two racked up $4.5 million in lobbying fees in L.A. last year — roughly a third from real estate — the newly merged firm is on pace to significantly surpass that this year. In 2019’s first quarter it took in $1.7 million, more than any other lobbying firm in the city. In addition, the firm has 16 L.A. lobbyists, second only to Latham & Watkins, the supranational law firm with L.A. roots.

Like many rivals, EKA generally hires former government staffers, said McConnell, who was a legislative deputy to former L.A. City Council member Nick Pacheco in the early 2000s before going to the private sector and then joining EKA in 2012.

In Beverly Hills, the firm has a long history with the high-profile parcel of land at 9900 Wilshire Boulevard.

It represented Chinese developer Dalian Wanda Group, helping to entitle the property and pave the way for a planned $1.2 billion hotel and condo project dubbed One Beverly Hills.

As part of that job, EKA also worked on the “No on HH” campaign — which was bankrolled by Dalian Wanda. That 2016 campaign defeated a referendum proposal that would have green-lit an adjacent condo and hotel by hotelier Beny Alagem and partner Cain International.

But in late 2018, Dalian Wanda sold its property to Alagem and Cain for $450 million, and EKA was hired by the new developers to keep lobbying for One Beverly Hills.

McConnell called the One Beverly Hills situation unique because of the firm’s history with the development site, but said it isn’t unusual to work against someone on one job and with them on another.

He recalled representing a community group negotiating with the Archer School for Girls in Brentwood over the school’s expansion plans. At the time, Archer was represented by Lucinda Starrett, a partner at Latham & Watkins, with whom he worked on other projects.

“Just because you worked against someone in one place doesn’t mean they aren’t a great person to work with on another project,” he said.

Azure Development’s affordable project in Boyle Heights

Ek, Sunkin & Bai

$4.3 million in 2018

Ek, Sunkin & Bai dissolved its operations, which were based in the 42-story One California Plaza in DTLA, this year. But the firm generated $4.3 million in lobbying fees in 2018 — with about a third coming from real estate interests, according to TRD’s analysis.

The firm’s website — which has yet to be taken down — notes that it was ranked the No. 1 lobbying firm by the Los Angeles Business Journal.

Despite parting ways, all three of the firm’s named partners remain active in L.A., specializing in public affairs and lobbying, and sources say they are on good terms with one another.

Howard Sunkin and Michael Bai each formed their own firms, while John Ek took a position as co-chairman at Mercury — alongside former L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa — and brought along many of his former employees.

Ek told TRD that much of his work involves acting as intermediary between developers and lawmakers.

“We find out what they want to see, take it back to the client to make sure they’re not pushing something their elected [official] doesn’t want, and we move things along as quickly as possible,” Ek said. “It’s also keeping it on the mind of the Council member.”

Among other real estate firms, Ek has represented construction giant AECOM, which in April secured $17.3 million in tax incentives for a 258-room hotel in DTLA.

And last year Sunkin lobbied the Council on behalf of Capri Capital Partners as the firm secured approval to add nearly 1,000 condos, a hotel, retail and office space to the aging Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza mall.

Armbruster Goldsmith & Delvac LLP

$3.6 million in 2018

Like many of the other top firms, Armbruster has a clientele that includes major national firms, like EQ Office — founded by Sam Zell and now owned by the Blackstone Group — and smaller local developers like Reseda-based Skya Ventures, which is working on a 92-unit project in East Hollywood with transit-oriented incentives.

The Westside-based law firm has 13 registered lobbyists who brought in $3.6 million last year, with about 80 percent of that coming from the real estate world.

Rand, who’s been at the firm for about eight years, said it’s not always easier to win approval for smaller projects.

He cited a five-unit subdivision in Silver Lake that his firm worked on, which was met with staunch community opposition versus the “exceedingly smooth” 2016 approval for toymaker MGA Entertainment’s redevelopment of a 24-acre site in Chatsworth as its headquarters.

The developer on the Silver Lake project, which Rand declined to name, eventually hammered out a settlement with the community group and moved forward with construction — but only after opponents challenged the project’s compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act.

Meanwhile, MGA’s project is wrapping up the first phase of its mixed-use development, which will also have 660 rental units and 255,000 square feet of office space.

“[The Silver Lake project] is the reason I don’t have a lot of hair anymore,” he said. “There were appeals, fights, legal letters, tit for tat. It’s really not tied to size, it’s really tied to the amount of controversy and the type of opposition there is to the project.”

Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton LLP

$3.4 million in 2018

Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton brought in $3.4 million last year in lobbying fees — around 60 percent of it from real estate interests.

The law firm’s clients include Don Peebles’ eponymous development firm, which is one of three developers partnering on the massive $1.6 billion Angels Landing mixed-use project in DTLA.

The trio won the project through a public RFP in late 2017. The developers were hoping to land an expedited environmental review, a move that would have sped up the timeline, but the city decided that the project required a full review.

Peebles — whose firm paid Sheppard Mullin nearly $130,000 in 2018 to work on behalf of Angels Landing — said the attorneys are negotiating the development agreement and leading contract negotiations with the city as well as ensuring compliance with state and city laws.

He said that given how complicated the process is — the project is currently working its way through the environmental review — the support is mandatory.

“Especially for a project of this scale, it’s critical that we have an experienced law firm making sure we dot our i’s and cross our t’s, because there’s no margin for error,” he said.

Craig Lawson & Company

Craig Lawson & Company

$2.9 million in 2018

Craig Lawson’s eponymous firm specializes in land use and securing entitlements and variances for development projects.

The firm has worked for some of L.A.’s most active developers, including CIM Group, Jamison Properties and Holland Partner Group, which have built millions of square feet of real estate.

Lawson has been active in the city for 30-plus years. The firm brought in $2.9 million last year, nearly all of which was from real estate developers or entities related to property entitlements in some way.

The entitlement process can take as little as six months if no variances or other zoning waivers are needed, or more than two years if a client is looking to lock in multiple approvals to significantly deviate from existing zoning.

Lawson’s firm worked on CIM Group’s once-embattled 299-unit Sunset Gordon tower in Hollywood.

“Our client asked us to pursue a long list of variances and exceptions from the zoning code in order to build a high-rise residential tower over office and retail space,” he said. “We said we could certainly file the application, but there was no guarantee that it would be approved.”

The city approved the project and CIM built it, but it’s sat vacant since 2015, when L.A. County revoked its permits because the developer had agreed to preserve part of an existing restaurant but failed to do so. (Lawson was not involved in that situation).

The county reissued permits in December, but a lawsuit over the number of affordable units in the tower remains in litigation.

More generally, Lawson said, he typically meets once or twice a week with a client’s development team, depending on how far along the project is. He may speak with a city official once a week — or once a month — about a project. “In each case, even one that fully complies [with zoning], you still have to interact with staff and other city officials,” he said. “So as a result we are lobbying per the city’s definition.”