Proposition 1

If passed, the first measure on the ballot would authorize the state to sell $4 billion in bonds to fund affordable housing programs for low-income residents, veterans, farmworkers, mobile homes, infill development and transit-oriented housing. This money would go into eight existing affordable housing programs and would not create new programs. About $1 billion would go toward funding housing for veterans, while $1.5 billion would go toward local governments and nonprofit builders creating housing for families making below 60 percent of the area median income. The remaining funds will be used for TOD implementation projects, regional planning initiatives and housing assistance programs.

What the opposition says:

Although little money has been spent to oppose the measure, opponents — including the editorial board of the San Diego Tribune — say affordable housing programs don’t do enough to address the issue and only help a small number of people.

What happens next if approved:

The state would have to sell the actual bonds and, if successful, would have a healthy chunk of change to funnel to housing programs around the state. Together with proposed legislation in Sacramento to allow for more residential density, it could help alleviate some of the pressure on Californians in need of housing.

Proposition 2

Aiming to free up cash for development, Prop 2 would use the millionaire’s tax to pay for housing for people with mental illness. The tax was created with the passage of Proposition 63 in 2004 and it taxed people an extra 1 percent on every cent they made over $1 million annually. The money was earmarked for mental health services and amended in 2016 to fund housing. A legal challenge stopped that, which prompted this ballot measure. Prop 2 would authorize the state to issue $2 billion in bonds for housing for people with mental illness and allow the state to pay back bonds with money raised through the millionaire’s tax. Proponents point to studies that say housing is a proven way to help people with mental illnesses. The money would go to counties to fund the housing development.

What the opposition says:

The opposition to Prop 2 is not strong, but those who do oppose it say the money should go only to treatment programs. The National Alliance on Mental Illness, Contra Costa, based in northern California, is one organization that opposes the passage of Prop 2.

What happens next if approved:

Like Proposition 1, the state would first have to raise the bond money before it could disperse any money to counties to fund housing.

Proposition 5

By shifting tax assessment rules, Prop 5 aims to boost the housing market while encouraging more older homeowners to downsize, thereby releasing more inventory into the market. It would allow homebuyers who are 55 and older, severely disabled or have a home destroyed or contaminated by a disaster to lower their property taxes when they buy a new home.

The state uses this example: Under current law, if a homeowner’s existing property’s taxable value — which is different from market value — was around $200,000, he would pay around $2,200 in property taxes. Existing law allows him to only transfer that assessment if his new home is valued at or below that price. If he wanted to buy a $700,000 home, he would have to pay $7,700 in annual taxes.

Proposition 5 would calculate a new home’s tax assessment based on the difference between its market value and that of the older home. So in that same case, the homeowner would only have to pay $3,300 in property taxes on the $700,000 home.

Proponents of the measure say existing law discourages older people from moving out of starter-to-midrange homes, keeping them off the market for younger buyers. It’s almost impossible to find homes now with a taxable value below the taxable values of homes bought in decades past, so there are few chances to take advantage of existing law.

What the opposition says:

The argument against passing Proposition 5 is mostly fiscal. The state predicts that the loss in property tax revenue to local governments around the state would be around $100 million in the first few years and eventually around $1 billion annually.

What happens next if approved:

If supporters are right, more moderately priced homes should hit the market, increasing supply, and bringing down prices across the board, but municipalities would likely see a loss in tax revenue.

Proposition 10

With the most widespread implications for Californians on November’s ballot, Prop 10 is the measure the real estate community is watching most closely. If passed, it would repeal the 23-year-old Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, which had prevented municipalities from putting rent regulations on single-family homes, condos and any rental units built after 1995.

Prop 10 would allow local governments around the state to expand rent control as they see fit. Passage of the ballot measure itself wouldn’t create new rent control laws, but it would create an environment of uncertainty for landlords and developers. Some developers have already held off on projects until after the vote. Supporters of the proposition argue that expanding rent control is the only way to sustain and increase the amount of affordable housing in increasingly expensive California. Pro-Prop 10 groups have raised $14.4 million to help pass it.

What the opposition says:

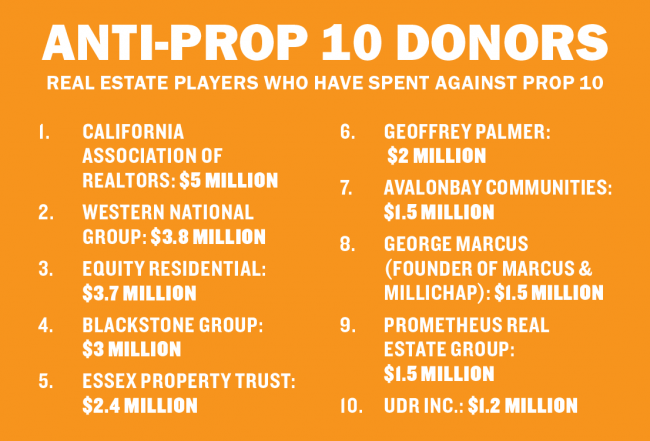

Opponents of the measure (many are people in the real estate industry) argue that expanding rent control laws would have the opposite effect from the outcome supporters say it will. If building and maintaining residential properties is made more expensive, fewer developers would build, and any stock they do bring to the market would have to be priced high to pencil out. Opponents of the measure have raised $48.5 million, according to California’s Fair Political Practices Commission.

What happens next if approved:

Besides an expected slowdown in investment and development, not much would happen right away. Each city around the state could immediately start drafting new rent control laws, but that could take months and potentially years in some areas.

Source: All donation data collected from California’s Fair Political Practices Commission