In Los Angeles, density is political, and in March, voters will decide if they want the city to temporarily put the kibosh on most large-scale development projects.

The Neighborhood Integrity Initiative (NII) would impose a two-year ban on projects requiring zoning changes. Only entirely affordable housing projects would be exempt — and only if they do not require changes to the city’s General Plan.

Backers of the anti-development measure, which is also referred to as Measure S, want to limit what they view as ultra-luxury, Manhattan-style projects that fail to address the needs of low-income residents. They also say that a suspension of all projects will afford the City Council the time and resources to focus on updating land use policies under L.A.’s 35 community plans.

But opponents of the initiative counter that zoning exemptions are often necessary because of the city’s outmoded planning process. Furthermore, they argue, putting the brakes on new construction would only worsen the affordable-housing crisis, and the exemption won’t help, they say, because many large-scale housing projects require General Plan amendments.

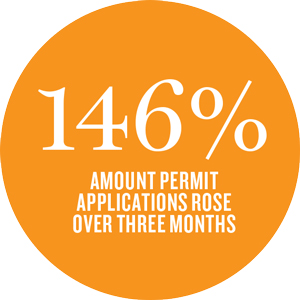

In a race against time, some developers appear to be filing building permit applications to try to get ahead of the March 7 vote. Applications soared 146 percent in the three months ending on November 30, 2016, compared with the same three-month period in 2015. The spike in building applications peaked in September, and market experts say that builders may have been calculating how many months they would need to win project approval by election day. But there is no guarantee that previously approved projects requiring zoning code exemptions would be grandfathered in should the initiative pass.

To further complicate matters, the Build Better L.A. initiative, an affordable-housing measure that passed in November 2016, could conflict with the March ballot initiative. The successful measure requires the developers of projects larger than nine units that need a zoning exemption to set aside up to 40 percent of the units for low-income households. The labor union-sponsored measure further compels developers to pay workers the prevailing union-approved rates. Politicians and the planning department are still working out how this will be implemented.

Nearly everyone agrees that the current situation is untenable. The city’s zoning code hasn’t been updated since 1946, when Los Angeles City Hall was the tallest building in town. Experts say that many of the community plans are long overdue for revision. Yet when planners have proposed updates to the community plans, local opponents have often emerged.

Nearly everyone agrees that the current situation is untenable. The city’s zoning code hasn’t been updated since 1946, when Los Angeles City Hall was the tallest building in town. Experts say that many of the community plans are long overdue for revision. Yet when planners have proposed updates to the community plans, local opponents have often emerged.

And when Angelenos don’t want new construction in their neighborhoods, they typically aren’t shy about challenging the project’s developers in court.

Where it all began

As it often does, this anti-development fight started out with a single project. The developer called it a much-needed boost to the local housing supply. The neighbors called it an eyesore.

Crescent Heights, a Miami developer, proposed the restoration of the historic Hollywood Palladium in 2013. The plan included Palladium Residences, a 731-unit housing complex that would create two towering condominiums on the theater’s parking lot.

But the towers would block the sweeping views from the international headquarters of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation on the 21st floor of the Sunset Media Center. And the organization and its president, Michael Weinstein, long known for their litigiousness, fought back.

When the City Council unanimously approved the project in March 2016, the foundation hired Robert Silverstein to sue the city for allowing zoning exemptions. Silverstein was already well known to city planners, having successfully fought their update to the Hollywood community plan three years earlier. The fate of the Palladium project remains uncertain as the lawsuit winds its way through the legal system.

But the AIDS advocacy group didn’t stop there. Instead, seeking to halt all large developments, Weinstein and the AHF drafted the NII ballot measure, then funded a group to promote it, the Coalition to Preserve L.A. As of November 2016, AHF had provided the coalition with $1.5 million. By January, the group had erected “Yes on S” billboards in all corners of the city. Neither the foundation nor the coalition responded to several requests for comment.

The root of L.A.’s planning woes

The most persistent argument that opponents make against the ballot measure is the city’s extreme housing shortage. Experts say L.A. is essentially at capacity because the current zoning would allow for about 4.3 million residents, according to a much-cited urban planning thesis by Gregory Morrow. The city’s population surpassed 4 million for the first time in 2016.

A series of policies in the latter half of the 20th century effectively reduced the city’s population capacity by restricting the density of building projects, a process known as downzoning. Along the way, layers of code were added that developers and planners say make development cumbersome.

“It’s just a dysfunctional process,” said Gail Goldberg, the executive director of the L.A.-based Urban Land Institute. “I don’t know when or where it went wrong.”

A major roadblock has been the cost of updating the outmoded building rules, said Goldberg, who served as the director of planning for the City of Los Angeles from 2006 to 2010. When Goldberg first assumed office in L.A., she was granted all the resources to start the process of modernizing the community plans. Then the recession hit.“The minute the economy wasn’t great, the first place they cut was planning,” she said. “If they’re going to update the plan now, they must commit to funding not only this year, but next year and the year after that. It’s a difficult thing to guarantee.”

For example, Goldberg worked on 10 plans during her four-year tenure leading the city’s planning department. By the time she left, only two of these had been adopted. Today, she said, 29 of the community plans are more than 15 years old, when ideally they should be updated every five years.

And then there’s the zoning code itself.

Community plans, according to city planner Deborah Kahen, were originally intended to be frequently updated in accordance with the zoning code so that the two worked hand in hand. A community plan was supposed to lay out the vision for a certain neighborhood, while the zoning code provided the general development rules in L.A.

But when it was first written after World War II, the zoning code was oriented toward cars and suburban development, said Kahen, who works for the re: code L.A. program, which was created to revise the city’s zoning code. She said the code does a poor job of addressing modern urban requirements. Over the years, rather than amending it, city planners have added hundreds of pages of site-specific conditions, which cover two-thirds of the city .

Mayor Eric Garcetti has said repeatedly that modernizing the city’s general plan and the community plans is a key goal of his administration. He said to do so, he intends to hire 28 new planners at an annual cost of $4.2 million.

In September, he told The Real Deal that in addition to directing his administration to update the general plan and community plans, he had pushed new efforts to make the environmental review process more transparent. “We will continue to work on reform, and accelerate wherever possible,” he said.

But prior efforts at reform have often fallen prey to not-in-my-backyard activism. Take, for example, the revision process to the Hollywood community plan. Planners spent years updating it — including holding over 60 public workshops, hearings and meetings — before it was approved by the City Council in 2012. The changes were intended to address the area’s projected population growth and to increase density in transit zones, such as the intersection of Sunset and Vine, which, perhaps not so incidentally, houses the Sunset Media Center, the home of Weinstein’s AIDS Healthcare Foundation.

In turn, neighborhood associations sued the city to overturn the new community plan for Hollywood. They hired Silverstein, the same attorney currently leading Weinstein’s battle against developer Crescent Heights.

In 2013, the L.A. County Superior Court ruled that the approval process had, in fact, not complied with the California Environmental Quality Act. Now Hollywood is back to using its 1988 community plan. Con Howe, who served as the L.A. planning director from 1992 to 2005, describes the battle against the revision of Hollywood’s community plan as “disingenuous.” He pointed out that it was approved by the City Council after a lengthy planning and review process. “And then these people sued.”

Despite the fate of the reform efforts in Hollywood, backers of NII are optimistic that the initiative would lead to updated plans. Regardless of what happens in March, planners say the real need is just a little bit of certainty, from which both community members — yes, even NIMBYs — and builders can benefit.