For too long, the area known as the Cornfield has been considered no man’s land.

The area, which straddles the up-and- coming neighborhoods of Chinatown and Lincoln Heights, has historically been home to a variety of industrial uses as well as freight rail yards, cutting potentially vibrant sections of the city off from one another and making development a diffiult, if not impossible, prospect.

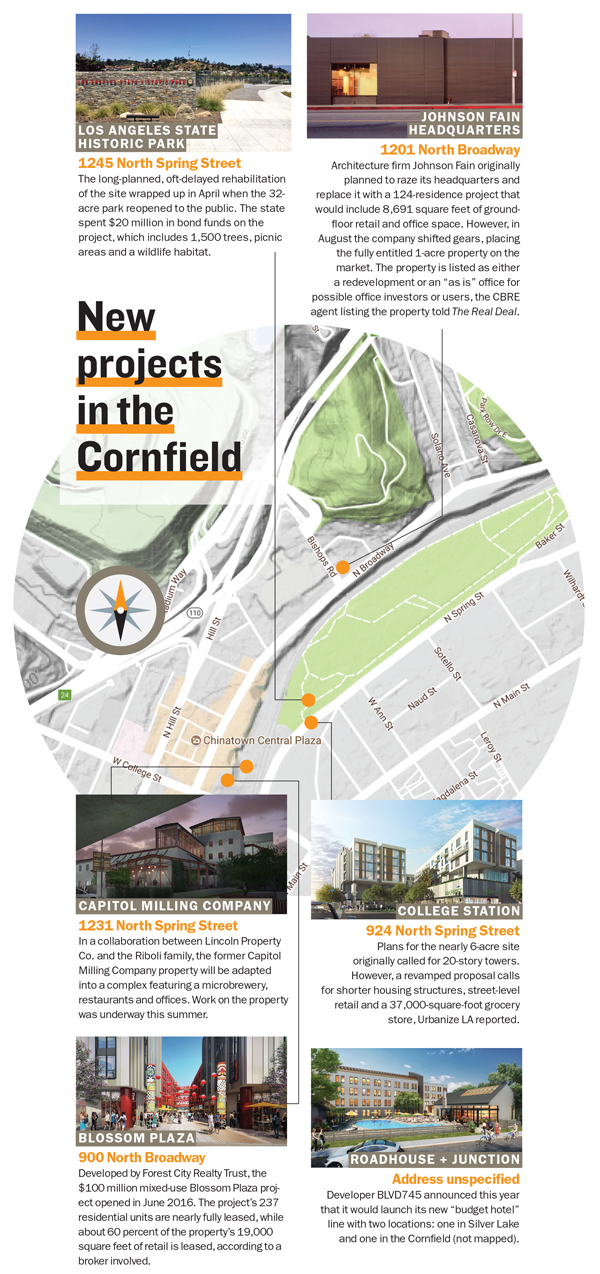

But now, thanks to factors including the recent transformation of a 32-acre former brownfield site into a park, zoning changes over the past few years designed to promote development in the area, and a host of buzzy projects opening soon, the Cornfield could be poised to become Los Angeles’ next hot area for development.

First, the history

There is no official neighborhood in Los Angeles called the Cornfield. Rather, the 660-acre swath of land given the informal name covers the northern section of Chinatown, the southern section of Lincoln Heights and the eastern portion of Solano Canyon — all of which are largely working-class, immigrant neighborhoods.

At the heart of the Cornfield sits a former brownfield site which, according to a KCET history of the land, used to be part of a farming operation, likely giving the parcel, and the area, their names.

In the late 19th century, the site served as a freight rail yard. However, the Southern Pacific railroad moved those operations to the Inland Empire in the early 1900s, leaving behind the large undeveloped property just outside of Downtown Los Angeles.

In the late 1990s, the cleared site became the center of a heated battle between developer Majestic Realty, which had planned the $80 million River Station Business Park at the site, and community and environmental activists, who had a different vision for the property.

Majestic promised the four-building complex would bring 1,000 new jobs to the working class community and had the backing of then-Mayor Richard Riordan. However, the alliance of activists was able to drum up support for the purchase of the land and eventually sued successfully to hold up the development. Subsequent ballot measures approved bond funding for the purchase and restoration of the site.

The oft-delayed project — which was famously kept in the public’s conscience by Lauren Bon’s 2005 art installation “Not a Cornfield,” which transformed the brownfield into an actual cornfield for an agricultural cycle — wrapped this spring when the Los Angeles State Historic Park opened in April. The $20 million project includes picnic areas and 1,500 trees, breathing new life into a long-overlooked tract of land.

The oft-delayed project — which was famously kept in the public’s conscience by Lauren Bon’s 2005 art installation “Not a Cornfield,” which transformed the brownfield into an actual cornfield for an agricultural cycle — wrapped this spring when the Los Angeles State Historic Park opened in April. The $20 million project includes picnic areas and 1,500 trees, breathing new life into a long-overlooked tract of land.

Creation of the CASP

Recognizing the value of the land surrounding the Cornfield, the city several years ago began looking at ways to encourage development in the area. The result of that process was the Cornfield Arroyo Seco Specific Plan (CASP), a planning document approved in 2013 that set guidelines for 660 acres of land in Chinatown and Lincoln Heights. The CASP, which runs through 2035, divides parcels into three different uses — hybrid industrial, residential multifamily and commercial manufacturing — while also setting aside some land for open space. Developers are granted an easier approval process so long as the uses comply and they meet certain requirements, such as floor-to-area ratio standards.

Most notably, the plan also represented an anomaly for city planning documents: It was the first and is still the only one of its kind to not include any parking requirements, eliminating the impact of ordinances that developers have loudly rallied against.

The idea was to promote smaller-scale, pedestrian- and bicyclist-friendly projects near the Cornfield, said Claire Bowin, a senior planner in the Los Angeles City Planning Department.

“It was really seen as an opportunity for the city to reshape what urban development meant in the 21st century,” Bowin said. “For us — and by us, I mean this global greater community that came together — it was saying, ‘Let’s have this be a model for how we can get around in a neighborhood without necessarily being so reliant on a car.’”

What’s already there

For all the hope, hype and optimism in the area, only a handful of projects have come online — which Bowin said has been “disappointing.”

“[The plan has] been heralded, which has been nice, and we’ve seen a lot of attention from developers exploring projects … But it hasn’t generated a huge groundswell of ground-up construction,” she said.

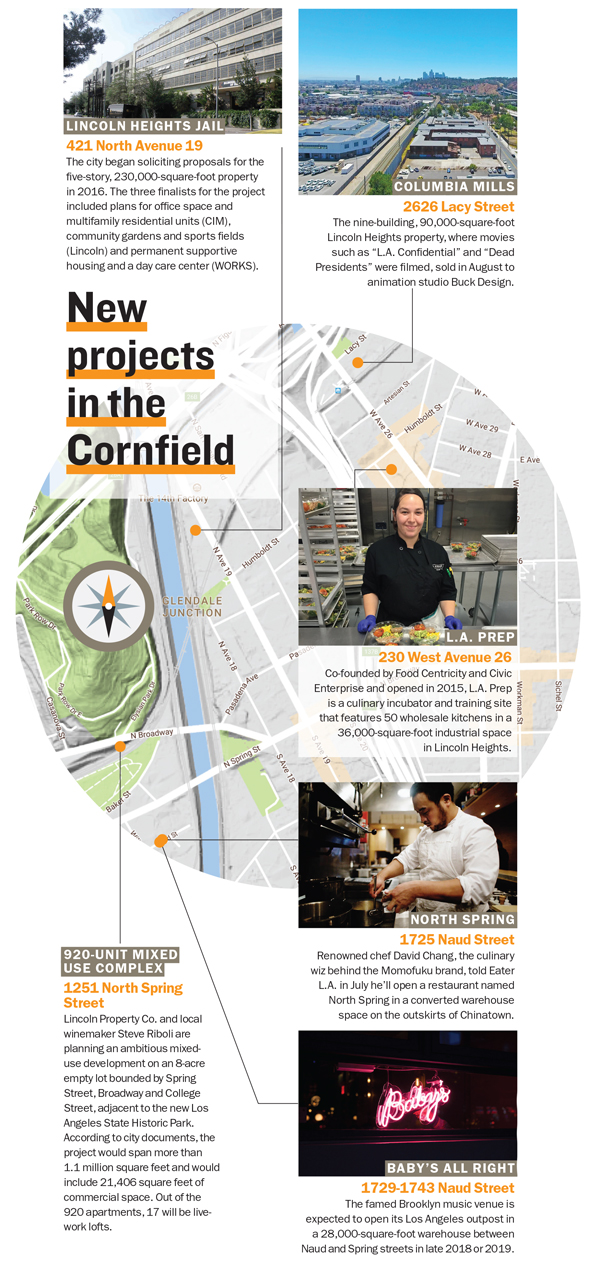

An early CASP success story is L.A. Prep, a culinary incubator and training site that features 50 wholesale kitchens in a 36,000-square-foot industrial space in Lincoln Heights, which opened in 2015. Mott Smith, co-founder and principal of Civic Enterprise — a partner in the project — said that the elimination of parking requirements and affordable industrial land prices were key draws to the property.

Smith said that the Cornfield area sits in “a fabulous location, ” but he worries the plan may be too prescriptive for many developers.

“We keep on forgetting in L.A. what plans actually do,” he said. “The main thing they do is they say you cannot build unless you fit inside a specific envelope.”

Smith said that many of the existing properties may have more value in their current use as industrial space — Los Angeles has one of the lowest industrial vacancy rates in the country, at 2.2 percent according to Colliers International’s second-quarter report — and developers are likely reluctant to purchase the sites for redevelopment given that there is a limit to what can be built there.

“The problem is this isn’t a farm somewhere at the edge of Bakersfield that’s being turned into a subdivision for the very first time,” he said. “This is an existing neighborhood with existing uses that are, frankly, quite valuable.” Industrial rents averaged $0.67 per square foot a month in the second quarter, according to Colliers.

Despite the slow start for development in the 660 acres identified in the city’s plan, there has been a slew of activity nearby — particularly at the northern end of Chinatown.

Among the first high-profile projects in the neighborhood is Blossom Plaza, a $100 million development that sits just outside the designated Cornfield area at the southern tip of the park. Developed by Forest City Realty Trust, the mixed-use building opened in mid-2016 and includes 237 residential units and 19,000 square feet of commercial space.

According to Lorena Tomb, CEO of Urbanlime, the company handling commercial leasing for the project, “a lot of people were initially concerned with being the first ones to get into that part of Chinatown.” However, she said a tipping point came within the past few years as more bars and restaurants announced interest in the area and the State Historic Park and Gold Line, which has a stop adjacent to Blossom Plaza, opened.

“I think that residents and the businesses that have started looking at Chinatown might’ve considered that market because it was not as expensive initially — the rents were still relatively affordable,” Tomb said. “I think what puts it on the map now is the completion of the [State Historic Park].”

Those factors have helped her attract businesses to Blossom Plaza. Already nearly completely leased on the residential side — with mostly younger people of various ethnic backgrounds moving in, Tomb said — the project currently has about 40 percent of its retail space open.

Tomb said that much of that remaining space is under negotiation. The project recently nabbed the owners of Downtown L.A. watering hole Ham and Eggs. They’ll open a wine bar in Blossom Plaza called L.A. Wine Co-op, while another bar operator (who wished to remain anonymous) will open “a really unique concept” that includes entertainment at the site, Tomb said.

Urbanlime also recently secured the operators for the project’s food hall, Potluck. They include a matcha restaurant named Young Bud, a mochi and Hawaiian shaved ice spot named Chichi Dang and a restaurant named Shrimp Daddy.

“We’ve seen things evolve over the past few years,” she said.

Next door to Blossom Plaza, Lincoln Property Co. and S&R Properties — both of which did not return phone calls and emails seeking comment for this article — are deep into a redevelopment of the five-building former Capitol Milling Company complex at 1231 North Spring Street. The companies, which are also partnered on a planned 920-unit mixed-use project at 1251 North Spring Street, are reportedly planning to put a microbrewery, restaurants and offices in 50,000 square feet at the Capitol Milling site.

The companies told The Real Deal in 2016 that they expect the surrounding area to be the “next district of DTLA to really see revitalization.”

“We see a great opportunity to … create enhancements for the surrounding community to enjoy — especially given its close proximity to Metro’s Chinatown station,” Rob Kane, head of Lincoln’s L.A. region, said at the time.

Build it and they will come

As for the developers exploring projects in the area covered by the CASP zoning, there certainly seem to be a lot of them.

Recently announced plans for several New York City mainstays to open Los Angeles locations in the Cornfield, in particular, highlight the evolving hipster nature of the area. Baby’s All Right, the Brooklyn music venue, and renowned chef David Chang, founder of Momofuku, announced separate plans this summer to open sites in the Cornfield area on Naud Street. The two will join New York’s famed Apotheke Cocktail Bar, which said in March it would open a spot at 1728 North Spring Street.

BLVD745, the boutique hotel developer behind the Ace Hotel and the Soho Warehouse in Downtown Los Angeles, announced this year that the Cornfield area would serve as one of two sites for its new “budget” concept: Roadhouse & Junction. Founder Jon Blanchard told TRD this year that the company planned to purchase a $27 million property near the State Historic Park and spend an additional $18 million to build a 130-room hotel on the site.

Calling the surrounding area a “thriving” community, Blanchard said that the zoning created by the CASP was a draw for him and his partners and that he expects the area to transform as a result.

“You will start seeing big movement with a tremendous amount of development in that area,” he said.

The city has also begun soliciting proposals for one of the Cornfield area’s historic landmarks: the five-story, 230,000-square-foot Lincoln Heights Jail. There are currently three finalists for the project — CIM, Lincoln Property Co. and the nonprofit WORKS — all of which presented their plans before a community meeting in August.

“If the project happens the way I think it will, that could be an amazing catalyst for change over there,” said Bowin.

And interest remains strong just outside the designated Cornfield area: Aside from the aforementioned mixed-use project planned by Lincoln Property Co. and S&R, there’s also the 25,700-square-foot headquarters of architecture firm Johnson Fain, which sits on the western edge of the park and was put up for sale by the company in August.

In 2016, Johnson Fain filed plans with the city to raze its one-story building and replace it with a 124-residence project that would include 8,691 square feet of ground-floor retail and office space. However, in August the company shifted gears, placing the fully entitled 1-acre property on the market. The project’s listing agent, CBRE’s Brad McCarthy, did not return emails requesting comment, but told TRD previously that the headquarters is currently listed as either a redevelopment or an “as is” office for possible office investors or users.

Developer Izek Shomof, one of the key figures in the redevelopment of Downtown Los Angeles over the last decade, is also betting big on the success of the area just south of the State Historic Park. Shomof’s Pacific Investment Group is planning a 122-unit, seven-story project on a half-acre lot at 211 West Alpine Street in Chinatown. The project is fully entitled, and architectural plans are currently being finalized, he said in an interview.

Shomof added that he views that section of the city as an extension of DTLA, and the increase in activity in the northern Chinatown and Cornfield area was a key draw.

“I personally believe that because of the demand that’s here in Downtown, it’s basically spilled over to the Chinatown area,” Shomof said. “There’s a huge demand. We have … many, many lofts in Downtown, and we are running at [near] 100 percent occupancy.”

Urbanlime’s Tomb said that she has recently spoken with developers interested in the area, including one from Vancouver. “We’re seeing foreign investors looking at this market as a potential for development,” she said.

What else could help the Cornfield grow

While the CASP has yet to spur all the development she had hoped it would, Bowin remains optimistic about the prospects for the area. She’s encouraged by the proposed projects, and she thinks that there could be even more interest in the Cornfield once the well of “tried and true” markets like Koreatown and the Arts District have dried up.

“Maybe once those areas get built out or the land prices get so obscene there, more people focus their attention on the [Cornfield],” Bowin said.

She’s also hopeful that a new wave of development will follow in the wake of the recently opened State Historic Park and another key public investment in the area: the restoration of the Los Angeles River. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is expected to begin work on the latter this fall. The project will return 11 miles of the concrete water channel to a more natural state.

Smith, who was part of the L.A. Prep project, agreed that the river “is the single most important investment that could impact activity in the Cornfield.” But he also said some smaller investments could go a long way in the area. Namely, he thinks improvements to make the neighborhoods more pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly are essential.

“Those actually make a really big difference,” Smith said. “The city’s general approach has been to try to get a developer excited and make the developer do all of those things. It’s not going to work like that in a place like the Cornfield.”