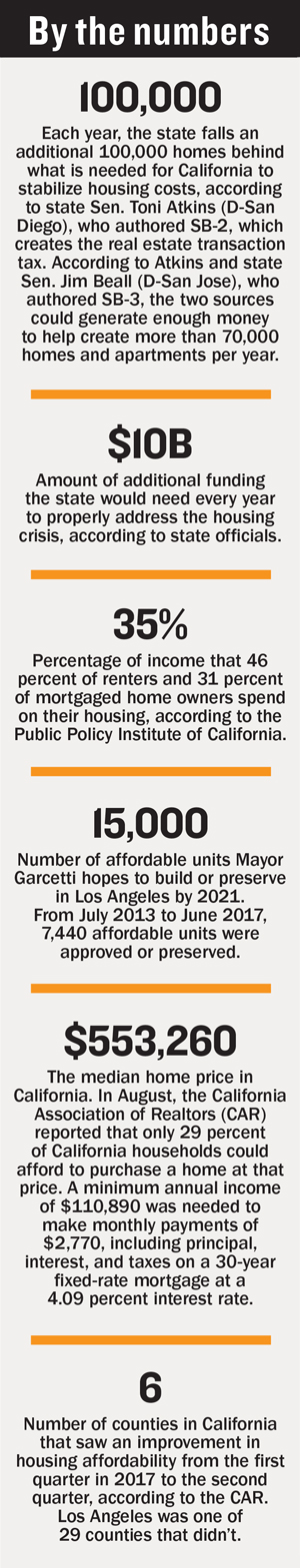

When Gov. Jerry Brown put his John Hancock on a package of affordable housing bills in September, advocates hailed it as a resounding success, trumpeting the new legislation as the state’s greatest hope for relief from the housing crisis and saying it would encourage a surge in development.

As a surprise to no one, developers and other real estate industry insiders are a bit more critical of the 15 laws, which they say don’t go far enough to clear up the red tape that makes California building intrinsically unaffordable.

Jonathan Genton, founder and CEO of Genton Property Group, said that while he supports the housing package, he doubts the measures will drastically increase affordable housing inventory.

“I am always an advocate of anything that addresses the supply of housing in the state,” Genton said. “[Some of the laws] will help subsidize the cost of affordable housing, but they will do almost nothing to enhance the supply.”

Whether or not it ends up being effective, SB-35 — which goes into effect on Jan. 1, 2018 — was written with the intention of creating more supply. The law will require California cities that lack adequate affordable housing to streamline their permitting processes. Those cities must approve all apartment and condo developments provided they comply with zoning laws and labor requirements and 10 percent of the units are affordable.

This will allow developers to skip the expensive and often years-long process that involves environmental impact reports, City Council votes and court challenges. Project height and unit count cannot be altered in the design review process, which will be expedited and focused on architectural design. Also, all minimum parking requirements will be waived.

Gov. Jerry Brown

Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office reported in August that more than 7,000 new affordable units have been financed or incentivized in the city since 2013, which represents less than 12 percent of the total housing units produced over that period — 58,527.

However, to meet the new state-mandated goals — which call for Los Angeles to build more than 50 percent of its developments as “very low income,” “low income” and “moderate income” housing — L.A. will need to approve thousands of affordable housing units.

“It’s good; it’s trying to put teeth in a toothless dog,” Genton said. “But maybe not in a strong enough way.”

Other developers in Los Angeles said SB-35 is a step in the right direction, but they also are worried that the bill includes too many restrictions and won’t make a noticeable impact on the development market.

“The legislation gives with one hand and takes with the other,” said David Waite, a land use attorney and partner at Cox, Castle & Nicholson in Los Angeles.

For example, accessory dwelling units can qualify for SB-35’s streamlining, but single-family-home developments will not. Proposals will not qualify if they include demolition of existing rent-controlled housing unless it has been vacant for 10 years. Projects must comply with local zoning laws in terms of height and bulk, and they must not exceed 200 feet in height.

Waite said SB-35 may not lead to as much new development as lawmakers are hoping for, because developers will still be “constrained” by L.A.’s outdated zoning standards. To build a residential project of any scale, he said, developers need to request zone changes to increase the floor area ratio allowed on a site. But that disqualifies the project from SB-35.

The city is working to update its decades-old community plans, which dictate what type of development is allowed in certain areas, and Los Angeles is currently modernizing its zoning code with its re:code L.A. program. But that process is years from completion.

“You’ve got to have the right zoning in place to stimulate development,” said Chris Tourtellotte, managing director at LaTerra Development. “If the right zoning is in place, people will build affordable housing.”

And there are more limiting qualifiers for SB-35. In addition to the mandate that projects include at least 10 percent affordable housing to qualify — which some say discourages developers — they must follow strict labor union requirements for construction.

And there are more limiting qualifiers for SB-35. In addition to the mandate that projects include at least 10 percent affordable housing to qualify — which some say discourages developers — they must follow strict labor union requirements for construction.

Developers told The Real Deal that development and the approval process need to be made easier and cheaper to make an impact.

“That’s a tough double whammy,” Tourtellotte said. “It’s a little bit too much. Labor requirements will be a problem for some people, and I think it’s going to have a negative effect on the bill. It’s economically unfeasible.”

Developers of five- or six-story housing projects — which historically have not dealt with labor requirements — could see costs increase by 40 percent, according to land use attorney Jerold Neuman, who has handled major real estate projects such as Millennium Partners’ Capitol Records and the Hollywood & Highland Center.

Nick Buchanan, president of Cape Point Development, which has constructed residential communities throughout Southern California, said mandating affordable housing is an overstep. It could push property owners to raise prices on market-rate units to make up for it, he said.

“Even if your project meets zoning, even in cities where you’re meeting community plans, they still can find a way to put you through the wringer,” Buchanan said.

Waite said Los Angeles needs to focus on removing barriers for market-rate and workforce housing as well.

“We need to limit regulatory obstacles to develop both types of housing to really tackle the housing crisis,” he said. “All boats rise with a rising tide.”

Taxing real estate transactions

Other aspects of the statewide affordable housing laws mine funding directly from both the real estate industry and its clients.

On Sept. 29, the governor signed SB-2, which will add a $75 to $225 fee on most mortgage refinancings and a range of other real estate transactions in California. The new tax, which will take effect on Jan. 1, is expected to generate a permanent stream of $250 million per year to help pay for affordable housing development in the state.

SB-2 is one of the new funding sources in the housing package that the governor said will help ensure “Californians won’t have to pay an arm and a leg to have a roof over their head.”

Robin Hughes — president and CEO of Abode Communities, which has developed affordable housing units throughout L.A. — said the funds from SB-2 will be a direct investment in affordable housing, which “needs to happen.”

“The thing about these funding sources is that they allow affordable housing developers to address a range of housing needs, to blend or layer the funding together,” she said.

Alyson Austin, with the real estate research firm CoreLogic, said a $75 tax will slow the volume of refinancing activity, but not by a lot. New York and Florida have a fee on mortgage recordation, and mortgage payment speeds are only “a little slower in those states,” she said.

Genton said the tax on transactions will be “so insignificant” to developer deals that it won’t slow the market at all. He also speculated as to whether the funds will “actually be spent on the problem,” saying that he has seen funds from housing bonds expire because cities don’t approve housing.

“This is the easiest thing to do: take money from peoples’ pockets and say it’s going to help,” he said.

Rolland Curtis Gardens, scheduled for winter 2018, will include 140 affordable family homes. Construction started in June at Exposition Boulevard and Wisconsin Street.

Other developers and real estate experts said the added fees could discourage real estate activity. The Building Owners and Managers Association of Greater Los Angeles (BOMA-GLA), which represents owners, developers and asset managers, called the fee an “outrageous tax increase” that will increase the cost of lot line adjustment filings sevenfold, from around $36 to $261.

“Our industry remains opposed to the new taxes contained in SB-2, as the bill is a regressive measure that inserts a convoluted tax into the middle of day-to-day real estate business and does very little to directly produce affordable housing,” BOMA-GLA said in a statement.

Voter-approved funding

SB-3 was also approved by the governor to create a new funding source, but it still has to be approved by the voters of California.

SB-3 would put a $4 billion bond proposal on the 2018 ballot to pay for affordable housing throughout the state, which means it would be at least a year and a half until developers would be able to benefit.

If approved, SB-3 would include $1.5 billion for the Multifamily Housing Program; $1 billion for the Cal-Vet Farm and Home Loan Program; $300 million for infill infrastructure grant financing; $300 million for the Local Housing Trust Matching Grant Program; and $150 million for the transit-oriented development program.

Lawmakers said the bond is also capable of leveraging nearly $11 billion more in federal tax credits. But Neuman said he is worried those federal funds might not come anymore.

“It depends on what the [Trump] Administration does, but tax credits are already drying up for affordable housing,” he said. “And I’m afraid these funds could just be backfilling those gaps.”

Neuman emphasized that he supports SB-2 and SB-3 and said the measures will help produce affordable housing. But he said the affordability gap was caused by many factors, and he doesn’t believe the state can “legislate or build into affordability that easily.”

Neuman explained that there are too many factors at play to be able to know exactly how and when these funding sources will affect development and the real estate market in Los Angeles. But he said he is worried the city and the housing package will not do enough to produce market-rate housing.

“None of the proposals have solutions for a family of four making $80,000 per year who don’t qualify for affordable housing,” he said.

He added that with local housing measures also in place, such as L.A.’s Measure JJJ — which also incentivized affordable housing and imposed labor restrictions — it will likely be years before developers know if or how effective each measure is for the city.

Tourtellotte said he doesn’t think SB-2 and SB-3 will be enough to give much help to L.A.’s housing market, and that they “won’t be too meaningful.” He said the state should use smarter incentives and fast-track measures like SB-35 instead of tapping into taxpayers’ money.