At 9800 Grape Street in the Watts neighborhood of southern Los Angeles, gone are the low-rise complexes that were the epicenter of the Rodney King riots. In their place stand rows of wood-frame skeletons taking the shape of 12 garden-style apartment buildings, the first phase of an ambitious redevelopment.

While funds for the first and second phases are largely being drawn from city and state coffers, the $500 million project known as Jordan Downs could soon tap into a gargantuan well of capital for the remaining eight phases. Much of the 1,600-unit project, it turns out, is a strong candidate to qualify for funding through a new federal program that developers see as one of the greatest tax-avoidance opportunities ever created in this country, and one that their industry is in a prime position to capitalize on.

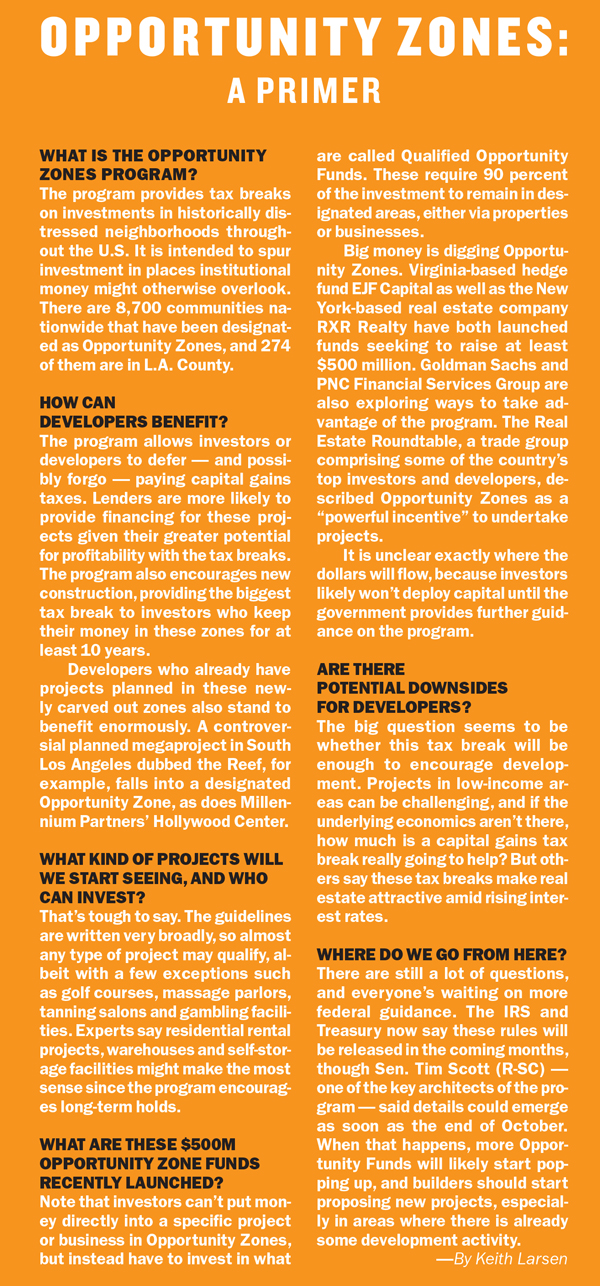

Tucked away in the Trump administration’s tax overhaul in December, the Investing in Opportunity Act, as the legislation is formally known, allows developers and investors who build projects in designated low-income neighborhoods across the country to get substantial capital-gains tax breaks and, in some cases, avoid paying the tax bill altogether. Unrealized capital gains by U.S. households and U.S. corporations represent potentially $6 trillion that could be eligible for reinvestment in Opportunity Zones, according to an analysis by the Economic Innovation Group, the think tank that championed the program. Investors can’t put their money directly into a given project in an Opportunity Zone, but can invest via designated Qualified Opportunity Funds.

“The Opportunity Zone Program could be the biggest thing to happen in real estate in my lifetime,” said Bryan Woo, an executive at developer Youngwoo & Associates, which is looking to raise a $500 million fund to invest in projects in the zones, including in L.A.

Cynthia Parker, CEO of nonprofit Bridge Housing, which is partnering on the Jordan Downs project with affordable housing developer Michaels Organization, said the program is “generating interest from a new asset class of investors who are new to affordable housing.”

In the city of Los Angeles, more than a quarter of upcoming residential units and nearly half of commercial space already lies in Opportunity Zones, according to an analysis by The Real Deal of ground-up new construction filed with the Department of City Planning from October 2017 through September 2018.

The tax breaks to be had increase the potential for profits and thus up the likelihood that banks and other lenders will back projects that may not have previously been considered financially viable. The program encourages new construction, since the biggest tax breaks are available to investors who keep their money in these zones for at least 10 years. This has led to builders scrambling to find projects in these zones, raise dedicated funds and deploy the cash by the end of next year in order to take full advantage of the program.

“Real estate people know it takes time to do deals,” Mark Edelstein, chairman of Morrison & Foerster’s global real estate group, said at a conference last month. “If they start [an Opportunity Fund] in July of 2019, they are toast.”

But not only are developers being forced to move fast, they are also moving somewhat blind: The Treasury Department and the IRS have yet to provide key details about the program, such as whether refinancings for existing projects and developments that are already in the works qualify. And for housing advocates and the communities they serve, there is a lack of clarity about what the program will actually deliver, and whether the money will flow into the areas that need it most. Is there a risk, say, of Opportunity Zones becoming the next EB-5, with a bulk of the projects being built catering to the ultra-wealthy instead of challenged communities?

“This is the biggest initiative of this type by the federal government with the least debate, the least staff support, the least research and still the least clarity,” L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti told the Wall Street Journal. But he did not appear particularly perturbed by the opaqueness of the program: “It hasn’t really been fleshed out and that’s exciting for me.”

An unlikely architect

What do Facebook, Spotify and a tax break that received love on both sides of the aisle have in common?

The answer: Sean Parker, the billionaire tech investor and co-founder of music-sharing pioneer Napster. Through the think tank he founded, the Economic Innovation Group, the hard-partying Parker was the unlikely driving force of the Opportunity Zone Program, working with Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC) to create a mechanism that would drive dollars into depressed communities.

“Instead of having government hand out pools of taxpayer dollars, you have savvy investors directing money into projects they think will succeed,” Parker recently told Forbes.

The 1,600-unit project known as Jordan Downs could soon tap Opportunity Zones funding to round out financing for the $500 million development.

In L.A. County, real estate players are moving to identify possible qualifying sites in the 274 census tracts designated as Opportunity Zones.

Investors who keep their Opportunity Zone property investments for at least five years receive a 10 percent tax break on their capital gains. If they hold them for seven years, it’s a 15 percent break. And they can eliminate paying all their capital gains taxes from an investment in an Opportunity Zone if they hold it for a decade.

States were given the ability to nominate areas to be designated as Opportunity Zones, and California was among the standout states in choosing areas that were particularly distressed, according to a study by the Brookings Institution. However, given the lack of clarity around how the program will work, there is some concern about investments being diverted to neighborhoods that don’t fit the bill of being impoverished, underdeveloped and economically stagnant.

The Brookings study noted that the program provides exceptions from the strict poverty or income thresholds for less-populous neighborhoods or for certain areas that adjoin qualifying low-income neighborhoods. “Furthermore, the poverty measures from Census used to define low-income areas include college or graduate students, which means affluent areas like those surrounding Stanford, Harvard, or Georgetown qualify,” the study concluded. “And the Census data dates as far back as 2011, when neighborhood economic conditions may have been much worse than they are in 2018.”

These loopholes raise concerns that the Opportunity Zone program could become the new EB-5, a controversial visa program that grants green cards to foreign investors who invest in job-creating U.S. projects. One of the major criticisms of EB-5 is that dollars have flown not into economically impoverished areas, but instead into ultraluxury condo projects in some of the country’s toniest neighborhoods, including Beverly Hills in L.A. and Tribeca in Manhattan. Developers, critics say, were able to do this by gerrymandering, stitching a wealthy census tract together with a high-unemployment area in order to qualify.

Other critics take issue with the economic underpinnings of the plan. The program won’t work as advertised because it is “based on the faulty notion that urban or rural deterioration results from excessive taxation undermining capital investment,” Timothy Weaver, an urban policy professor at Albany State University, wrote in a recent op-ed for CityLab. “Sadly, these policies almost inevitably result in tax giveaways for investment that would have occurred anyway, as we’re beginning to see with Opportunity Zones,” he said. “Under such circumstances, displacement from gentrification is the likely result.”

Other critics take issue with the economic underpinnings of the plan. The program won’t work as advertised because it is “based on the faulty notion that urban or rural deterioration results from excessive taxation undermining capital investment,” Timothy Weaver, an urban policy professor at Albany State University, wrote in a recent op-ed for CityLab. “Sadly, these policies almost inevitably result in tax giveaways for investment that would have occurred anyway, as we’re beginning to see with Opportunity Zones,” he said. “Under such circumstances, displacement from gentrification is the likely result.”

Already, the industry has pushed back on recommendations that the government more closely vet Opportunity Funds to ensure that they will actually create more affordable housing.

The Real Estate Roundtable, an influential national trade organization whose board includes leaders of the Blackstone Group, Brookfield Property Group, Eastdil Secured and the Related Companies, wrote in a June letter to the Treasury and IRS that “Treasury review of the organizational documents of a QOF [Qualified Opportunity Fund] would create an unnecessary ‘bottleneck’ that would delay economic investment in low-income communities.”

Jockeying for position

The competition for Opportunity Zone investments is going to get intense in the coming months as developers and commercial brokers start putting together game plans to show why their projects are worthy of funding. In the city of Los Angeles alone, 35 out of 105 new construction projects with pending site-plan review applications filed between October 2017 through September 2018 are in designated Opportunity Zone areas. Those 35 projects have a total of 4,022 planned residential units, which represent 27 percent of the 14,756 residential units in the pipeline, according to TRD’s analysis.

One of the largest residential projects lying inside an L.A. Opportunity Zone is Hollywood Center, a long-stalled $1 billion project being developed by Millennium Partners. The mixed-use development will have 35- and 46-story towers, two 11-story buildings and underground parking. It is slated to bring 1,005 residential units to market, including 133 set aside for “extremely-low-income” and “very-low-income” seniors.

On the commercial side, a major project within an Opportunity Zone is Hudson Pacific Properties’ Sunset Gower Studios. A year ago, Hudson Pacific submitted plans to add 628,000 square feet of production space while tearing down 160,600 square feet of existing buildings at the 16-acre campus at 6050 West Sunset Boulevard. A spokesperson for Hudson Pacific did not respond to requests for comment.

Real estate lawyers and advisory firms are sprinting to set up practices that can assist developers in tapping into the new well of investor money. For instance, the national law firm Husch Blackwell recently set up a practice consisting of seven partners, four associates and two senior counsels “to provide clients coordinated direction on the federal Opportunity Zones program,” according to the firm’s website. Another law firm, K&L Gates, touts services such as developing fund projects that meet investors’ needs and objectives, compliance with securities laws and determining the eligibility requirements for qualified Opportunity Zone projects.

Paul Silvern, a partner with real estate consulting firm HR&A Advisors, said his firm “will focus more on working with people managing the funds to make good investments, and also to make sure the funds are directed in a way that produces public benefits. We would also play a role assisting public agencies to maximize their chances to get Opportunity Zone investments that work in conjunction with other programs like tax increment financing.”

Some local L.A. brokers are also starting to market properties by emphasizing their connections to the program. RPM Commercial Real Estate, for example, is promoting an $8.5 million listing for a 6.71- acre redevelopment site in Victorville, a city in nearby San Bernardino County, by highlighting its location in a newly created Opportunity Zone.

“We were thinking automotive retail or a two-story office building would work well on the site,” said RPM’s owner, Danny Raffle. “The main issue is finding tenants willing to lease whatever space is built. Then the property could tap into investor funding through the Opportunity Zone designation.”

Even institutions like the Kresge Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation are jumping in. In June, the foundations teamed up to offer grants and unfunded guarantees of up to $25 million for managers interested in creating funds for Opportunity Zones. The foundations received applications from 141 fund managers over the summer and selected 20 to work with.

Kimberlee Cornett, who oversees the Opportunity Zones assistance program for Kresge, declined to identify the fund managers, noting that the announcement won’t be made until the first quarter of 2019, though she did say most of the successful applicants have experience working in low-income communities. Taxpayers will want to see that the concessions the federal government has made on capital gains taxes were a good trade-off, she said, adding, “There has to be a mechanism that can show whether low-income communities received a meaningful, lasting investment.”

Michael Banner, CEO of Los Angeles LDC, a finance brokerage, said he wants to create a $10 million Opportunity Zone fund for projects in Crenshaw, the neighborhood he grew up in. His firm also owns a commercial property near Albion Riverside Park that is in a designated Opportunity Zone just outside of Downtown L.A., Banner said.

“We had taken back the building from a guy whose fortunes had changed,” he said. “We’ve been holding on to it for three years and now, poof, it’s an Opportunity Zone. If it can be redeveloped, this property can give investors a way to take advantage of the tax benefits.”

The flip side, Banner said, is convincing investors that they can make money in Opportunity Zone projects and that they are not assuming a substantial amount of risk.

“Historically, these communities have lacked access to capital,” he said. “To create value, then somebody has to pay for that value. Usually, that means charging more rent. It’s a matter of striking the right balance.”

Gray areas

Despite the enthusiasm for the program, the real estate industry is treading cautiously given that the IRS has not yet released the final rules and regulations.

Youngwoo’s Woo said that without total clarity, investors can’t make any commitments. “We need guidance from the IRS before anything can move forward,” he said. “It is hard to raise any capital right now under the umbrella of an Opportunity Zone.”

Bridge Housing’s Parker said her firm has been putting together a lot of different possible scenarios. “We have the broad brush strokes of what we can offer,” she said, “but we won’t have a final painting because the final regs have not come out.”

“Only a simple, streamlined regulatory framework will allow Opportunity Zones to unlock capital and achieve a magnitude of investment in low-income communities that results in transformational economic development and job growth,” the Real Estate Roundtable wrote in its June letter.

But developers may not have to wait around too long. Sen. Scott recently said that more details could emerge as soon as the end of October. And he’s confident that the program will make an immediate and significant dent.

“Some have suggested it will be three digits,” he said of the dollars that will flow into opportunity zones. “So it would be a $100 billion investment in the next couple of years, which I think will be realistic.”

Editor’s note: This story went to print before the IRS and U.S. Department of Treasury published its first set of rules for the Opportunity Zones program on Oct. 19.