When attorney Ellen Berkshire argued that her client Macy’s was overcharged for property taxes in 2018 on its flagship store in the Chicago Loop at 111 North State Street, she claimed the government’s appraisal mischaracterized it as an office building.

It wasn’t one yet — Brookfield Asset Management had only just agreed to pay $27 million for the sprawling retail property’s upper floors, which it has since converted into offices.

Berkshire’s evidence reduced the assessment on the property from $29.7 million to $25.5 million through a settlement with government lawyers, saving Macy’s on its taxes for the year; she had tried to push for an $18.5 million tax value.

While she settled that case, Berkshire asserted that her law firm, Verros Berkshire, is more willing than others to take its pleas for property tax refunds to hearings before an obscure state agency in charge of overseeing tax appeals from downstate homeowners and landlords of Chicago’s biggest buildings alike.

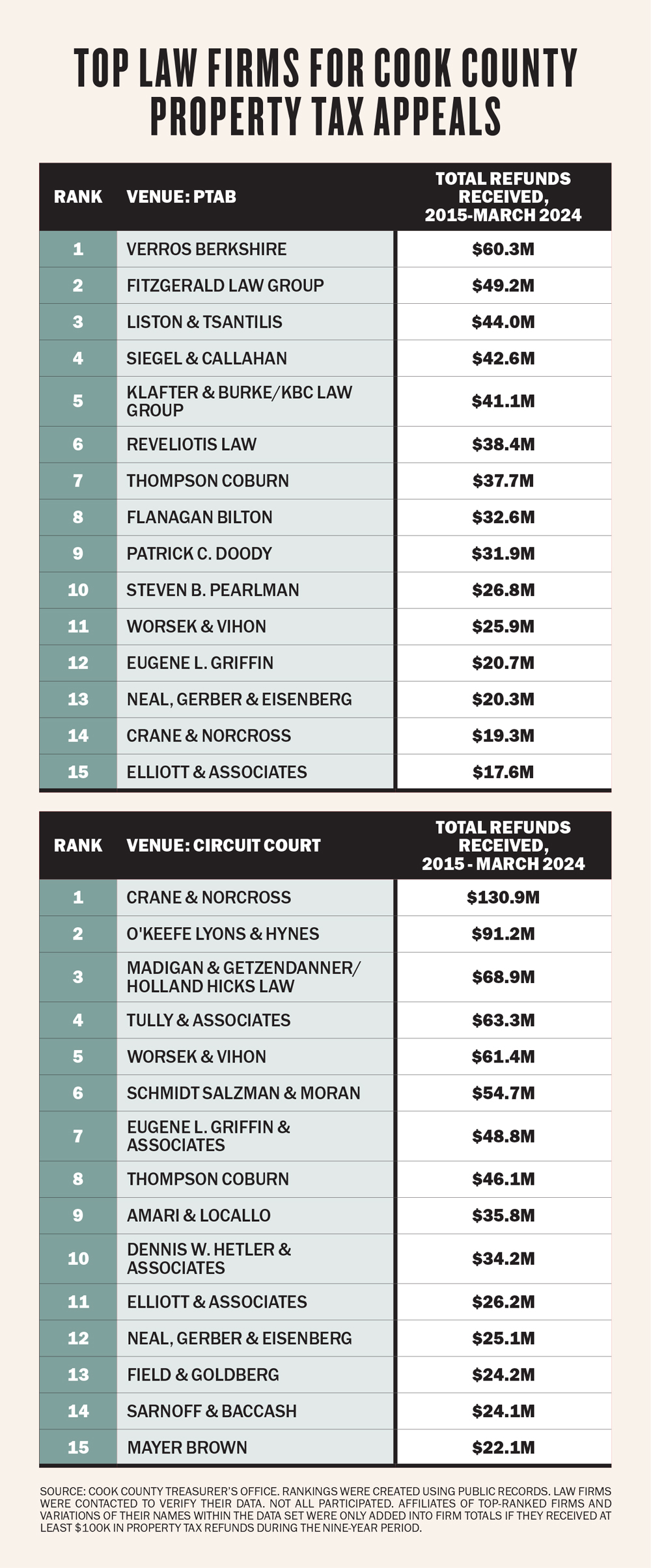

That’s how the firm racked up $60.3 million in tax refunds for Cook County property owners from 2015 through March this year to land the top ranking among law firms filing cases with the Illinois Property Tax Appeals Board (PTAB), according to The Real Deal’s analysis of records from the Cook County treasurer’s office.

“A lot of these refunds haven’t been settlements, and we’ve gone to a full hearing before PTAB on the merits of the case, expert versus expert,” Berkshire said.

But law firms such as hers might have to make big changes if one of the reforms being called for by powerful Chicagoland public officials comes to fruition in their attempts to stop the bleeding out of cash-strapped local governments.

The influence of the PTAB has been jeopardized by proposed legislation, potentially stripping what Berkshire and other attorneys in her field say is an important right for property owners — and a lucrative source of revenue for their lawyers, who normally take a cut of refunds they win as compensation.

Collateral damage

Berkshire and fellow attorney Mary Kate Fitzgerald, whose law firm ranked second in PTAB refunds, admit that their real estate specialty within Chicago’s legal field has seen its reputation diminished. The industry suffered black eyes after drawing attention from criminal investigators.

With former Chicago Alderman Ed Burke’s recent felony convictions for using his political influence to steer business to his property tax appeals law firm, and former Illinois Speaker of the House Michael Madigan, another top property tax appeals lawyer, facing trial in a separate public corruption probe, it’s easy to see why the legal niche’s image has been tainted.

Cook County Assessor Fritz Kaegi senses this, too, and in recent years has pushed to take PTAB away from taxpayers. The appeals board is a key tool for them — and their lawyers like Berkshire and Fitzgerald, who have successfully argued that local governments overcharged nearly $2 billion total since 2015, public records show.

“The pressure from Kaegi’s office has forced practitioners to take a more intellectual stance,” Fitzgerald said. “He has created a lot of new problems as well, though.”

She and her competitors fiercely oppose Kaegi’s idea for reform. The assessor, along with state lawmakers and the nonpartisan think tank Civic Federation, has pushed to eliminate Cook County’s exposure to PTAB. Such proposals have been filed at the state level, but scaling back the agency hasn’t become law.

“PTAB is catering to the worst inequities we have in our property tax system,” Kaegi said.

The quasi-judicial panel consists of hearing officers who review objections to tax bills across Illinois at all levels of real estate.

Property owners can only contest their tax bill after going before their county’s Board of Review — the first venue where taxpayers can seek relief by pointing out mistakes in assessments by Kaegi’s office or its equivalent elsewhere.

If Cook County taxpayers don’t get what they think they deserve at the Board of Review, they have to cough up the taxes charged for that year and then file appeals with either PTAB or the Cook County Circuit Court, where complaints are called “specific objections.” Even if they have winning arguments, backlogs in both venues mean that taxpayers might not see refunds for years.

“Nobody really wants to end up going to PTAB or specific objection. It’s not good for your client,” said Fitzgerald, whose firm, Fitzgerald Law Group, has pulled in $49.2 million in PTAB refunds since 2015.

Battlefield strategies

Law firms take their cut from clients’ refunds after guiding them through the process, and tend to prefer one venue over the other. The processes and rules differ between PTAB and the courtroom.

Either route is good business for the lawyers. While Kaegi pushes to cut off Cook County from PTAB, more money has flowed back to landlords and homeowners — and their lawyers — through Circuit Court. There, tax appeal cases almost never go to trial, and settlement agreements with the State’s Attorney’s Office tend to draw less scrutiny from school districts and other local government bodies that have to pay back overcharged taxes, experts said.

Collectively, the top 15 law firms for property tax appeals through court have reclaimed $753 million from Cook County governments on behalf of clients since 2015, public records show. They were led by Crane & Norcross, which notched more than $130 million in refunds; overall, a little more than $1 billion was returned to resolve court cases involving tax appeals over the period.

That compares to $508 million reclaimed by the top 15 legal performers at PTAB during the timeframe; the agency returned $868 million total to law firms and their clients, records show.

If PTAB gets peeled back from Cook County, it would create an even bigger backlog in court, as Kaegi campaigned on raising what he thought were artificially low commercial and industrial property tax bills when he first won election in 2018, lawyers said.

“We are seeing clients with assessments double, triple and quintuple,” said Mike Elliott, whose firm Elliott & Associates is a top-15 performer in both court and PTAB. “When you are sitting there with a $100,000 tax bill and it goes to $400,000, it’s a bad day for you, and you are not just going to give up. It’s a matter of survival.”

Kaegi points out that PTAB’s jurisdiction extended into Cook County relatively recently. It was considered an experiment when Republicans held control over state government in the late 1990s and spread the agency’s reach into Chicago, he said.

“Since then, we’ve had a mushrooming of fiscal outflow and appeals [at PTAB] and attendant disadvantages creating and doubling down on inequities in the property tax system,” Kaegi said. “I think PTAB is entirely superfluous.”

Previously, Circuit Court was the only option for Cook County taxpayers if they lost their case at the Board of Review and wanted to elevate it. In the mid-2000s, Gov. Rod Blagojevich, now a convicted felon, took a run at slicing PTAB’s influence by cutting its staff and resources, according to Michael O’Malley, executive director of PTAB.

Passive resistance

In some ways, PTAB does offer more protections than court to the taxing bodies faced with the possibility of refunding money they’ve already spent, lawyers said.

The Board of Review is charged with preventing assessments from being lowered by PTAB. And any PTAB cases involving more than $100,000 in disputed valuation trigger automatic notices to impacted taxing bodies such as school districts, which can choose to intervene in the case and bolster the Board of Review’s defense with their own attorneys.

No heads-up to taxing bodies is required from landlords and their lawyers who object in court.

“I’m a little perplexed by why Kaegi would want to shut down PTAB, because that’s what gives taxing districts some idea of where their exposure is,” said Ares Dalianis, an intervening attorney who represents school districts and other government bodies in fighting against refunds. “If that went away, every refund that came through would be a big surprise.”

Most refunds granted at PTAB are also done through settlements negotiated by taxpayers or their lawyers with the Board of Review or intervening attorneys, but some cases do go to hearing.

“Some tax attorneys prefer to come to PTAB because I would say we probably have more subject matter expertise,” O’Malley said, noting that Circuit Court judges also handle election law complaints and other cases.

In addition, Cook County Board of Review officials are trying to ramp up their defenses at PTAB, developing databases that would make them more persuasive when arguing against providing refunds in smaller cases. Historically, they’ve only had enough resources to concentrate on the biggest disputes.

Another argument in favor of keeping PTAB for Cook County is its label as a “poor man’s court.” There’s no fee to file an appeal other than paying your taxes up front, unlike in Circuit Court, where filing costs around $400. Most PTAB cases involve residential property, while the court tends to draw a larger proportion of big commercial owners, experts said.

“In the assessor’s defense, when he took over that office six years ago, there were chronic undervaluation problems with several property types,” Dalianis said. “He’s been criticized. A lot of people were very comfortable with the old system.”

Fitzgerald agrees that Kaegi has made some improvements to his office, though she and others questioned whether it was appropriate for him to throw his weight into March’s Board of Review election, when he funded an unsuccessful challenger to board Commissioner Larry Rogers Jr., one of the assessor’s biggest critics.

That move, along with Kaegi’s push to remove PTAB’s hold over Cook County, fueled claims that the assessor wants to remove checks and balances on his office, whose job is to evaluate nearly 2 million properties — a task experts say is bound to result in errors.

“Isn’t it clear that Kaegi is trying to influence every element of the landscape here?” George Reveliotis, one of the top PTAB lawyers, said.

Yet former assessor Joseph Berrios raised eyebrows with valuations that some Cook County residents considered giveaways to tax appeals lawyers — an industry that often funded Berrios’ political ambitions and continued to finance Rogers’ this year. Berkshire said she refrains from donating in such races.

“I think Kaegi’s heart is in the right place,” Fitzgerald said. “His methodology may be something I disagree with.”