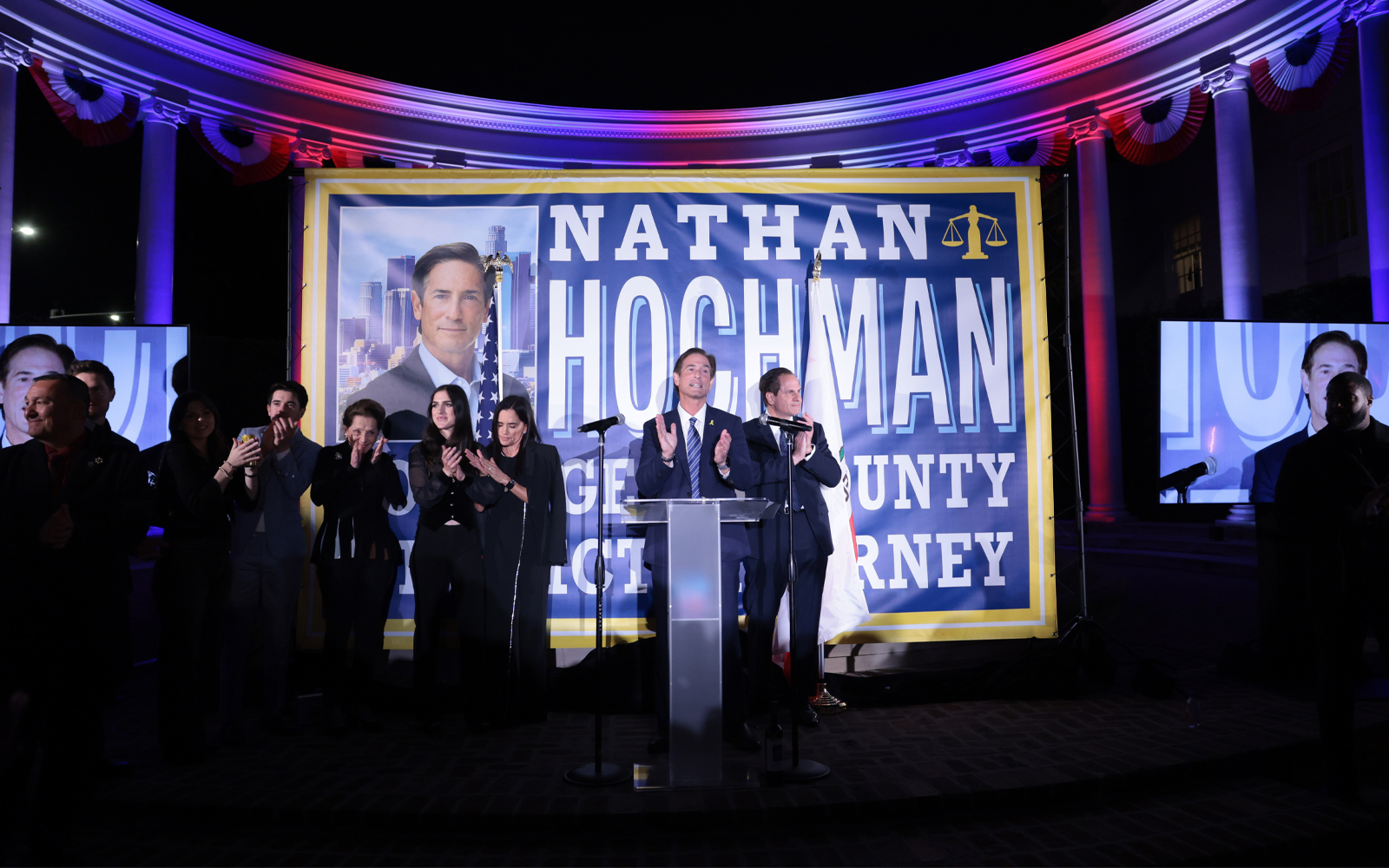

Nathan Hochman’s campaign had been in celebration mode all day.

The former federal prosecutor was about to unseat Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón, and anyone invested in real estate in the county was popping the champagne.

Gerald Marcil, Hochman’s biggest donor, and the founder and CEO of multifamily firm Palos Verdes Investments, preferred beer. He was at a South Bay sports bar with friends, where he always watches the results come in.

“Jerry,” as the bar owner calls him, has been in the housing business for half a century. He has about 7,000 housing units in his company’s portfolio and is always on the lookout for his next value-add investment, like the one he snapped up earlier this year in Orange County — not L.A. Palos Verdes added a 254-unit apartment community in Anaheim to its holdings for $79 million in February.

Yet, he’s afraid California is on the wrong track.

“No neighborhood is safe anymore,” he said. “My tenants are not living in bad areas, but they’ve become bad.”

That voters elected Hochman, agreeing with at least the spirit of his declaration, seemed like an overnight about-face from the election of progressive Gascón four years earlier, especially since Californians also rejected another progressive priority — reopening the discussion on rent control. Though the election of one moderate district attorney hardly means California is going conservative, the results also seemed to suggest property owners’ priorities had gained sway in the state.

Marcil knows the Southern California housing business is not for the faint of heart. Palos Verdes found a sweet spot in what he describes as the “B” area market — speculative zones that usually exist on the edges of “A” areas without being “too rough.” The outskirts of Manhattan Beach are a good example, he said. While beach views fetch premium prices, mid-market offerings a few miles inland butter Marcil’s bread.

“In a B area, you can make a difference,” Marcil explained. “When you fix up a unit and get a good tenant, you can make some money.”

He has made plenty of it, but he’s also known for sharing his success, and not just with candidates.

He’s a household name in Torrance, California, where he was born in 1953 and now serves on the board of the local YMCA, gives to the local school district and is the biggest donor to the Switzer Center, a private school for children with special needs.

“This new D.A. in town”

The D.A. race was a decisive battle for Marcil, but he appeared cool and collected five days before the general election.

“Nathan Hochman is my number one priority,” he said. “It’s the most important race to the quality of life in this county.”

When he won, many in real estate applauded: Residential brokers, luxury developers and commercial owners had all gone in favor of Hochman. They saw the impact of Gascón’s policies directly.

Marcil was particularly incensed when a man who had been caught and imprisoned for attempted arson at one of his apartment buildings in Harbor City was released early.

“No neighborhood is safe anymore. My tenants are not living in bad areas, but they’ve become bad.”

“I think he got four years,” he said. “But about 10 months later I got a call. ‘We got to let you know something. There’s this new D.A in town. His name is Gascón, and he let your guy out,’” he recalled. “I have to tell my manager to keep an eye out. It’s scary.”

Marcil went all out for Hochman, donating $550,000 to his campaign directly and via an independent committee, the LA Times reported. (He had also helped fund Hochman’s unsuccessful run for state attorney general in 2022.)

That makes him the largest individual contributor to either side of the D.A. race this election cycle.

What’s more, Marcil made sure Hochman’s campaign was top on the agenda of New Majority, an influential group of about 300 fiscally conservative, business leaders founded in Orange County in 1999. Its political director, Tom Ross, describes the founders as a group of philanthropists frustrated with politics who decided to get involved.

Now it is California’s largest Republican political action committee. Marcil has been the chair of the L.A. County chapter for the past 10 years.

If the organization is an advocate for change “in these times when things are changing in California,” as Ross put it, then you can see Jerry as the epitome of that mission.

The mission was now about law and order, and that seemed to connect with Angelenos newly concerned about public safety.

Hochman promised to “make crimes illegal again” and vowed to restore a sense of normalcy to the criminal justice system in the nation’s most populous county.

He won easily on Nov. 5 with 60 percent of the vote, declaring victory about 90 minutes after polls closed in California.

Justice on the ballot

In the wake of George Floyd’s death, Gascón campaigned on a progressive platform aimed at criminal justice reform and won in 2020. Voters, however, appear to grow weary of the experiment amid increased public perception of crime in the county.

An attempt to recall Gascón in 2022 failed. Marcil contributed $1.3 million to the effort, according to the Times.

Proponents of Gascón have long pointed to crime statistics, which appear to be on the decline this year: The L.A. County Sheriff’s Department reported violent crimes up less than 1 percent in the first nine months of 2024 compared to the year-ago period. But property crimes for the same nine-month period rose 2.3 percent.

“The voters of Los Angeles County have spoken and have said enough is enough of D.A. Gascón’s pro-criminal extreme policies; they look forward to a safer future,” Hochman said in a statement.

It’s not just L.A.: In Alameda County in the Bay Area, voters were seemingly on the same page. Pamela Price, who began her term as district attorney in 2023, was recalled, and a new district attorney will be appointed by the Board of Supervisors.

That these are attention-grabbing races at all speaks to the frustrations of Californians. Very few of the races in 2,300 U.S. jurisdictions that elect a top prosecutor are competitive. Only one in three D.A. candidates even face an opponent, according to a 2020 study by UNC School of Law.

But in L.A. County, it’s a big job. Hochman will oversee a staff of close to 1,000 deputy district attorneys who prosecute major crimes across the county. Gascón had hoped to bring an end to the most punitive practices that prosecutors adopted across the country in the 1990s, but he quickly fell out of favor with the office’s rank-and-file.

What doesn’t kill you…

To Marcil, Hochman’s victory was an obvious harbinger of the shifting national mood.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom wasted no time in the following days calling for a special legislative session to “Trump-proof” the state ahead of President Donald Trump’s return to the White House in January.

Marcil found the governor’s antics perturbing. He said he cast his ballot for Trump this year, although he doesn’t broadcast that widely in California. And New Majority, for its part, typically stays out of presidential races.

“I voted for policy over personality,” Marcil said. “It was an easy choice.”

His politics are derived from his personal history.

Marcil trained from an early age to be a machinist, his father’s trade. The work helped him put himself through community college, El Camino College in Torrance. He won a scholarship to the University of Southern California.

He set his sights on becoming a developer early on, but the business did not pay off for a while.

Twice Marcil teetered on the brink of failure: He was ill-prepared when interest rates soared and the United States economy tanked in 1980 and was hit hard again ten years later.

“I was the most broke because I owed more than I was worth, a lot more,” he said.

He learned some important lessons: Hard work doesn’t always pay off when luck — or policy — is bad. He also realized that there was more to life than business. “I’m not my money,” he said.

As if to prove it, Marcil gave money away. Long before he ever got involved in campaigns or ballot measures, he had a track record as a philanthropist. One recipient: a YMCA summer camp, which is now named after him.

Rent regulation has also caught his attention recently. Local laws limiting annual rent hikes are now on the books in some of Southern California’s most valuable housing markets, including Santa Monica.

“The government is massively stupid.”

Like most in the industry, Marcil views rent control as a cosmetic fix that does nothing to address the anti-development syndrome at the root of California’s housing crisis.

It’s just another piece of evidence backing one of his most firmly held beliefs, namely: “The government is massively stupid.”

He can count the ways.

“Two years ago we had a $100 billion surplus in this state,” he said. “It’s now a $68 billion deficit. We don’t have a printing press like the federal government, and so now they’re cutting back on all kinds of services and everything, and it’s their own fault. They’re just making so many mistakes — bullet trains that don’t work that we spent how many billions on that just an example. We lost $31 billion during Covid, just in the unemployment benefits.”

Not a gold rush

Palos Verdes’ recent multifamily buy in Anaheim notably isn’t in L.A. but rather Orange County, which has been resilient, with 4 percent vacancy rates.

The purchase also does not seem to have been a vote of confidence in the state.

“It’s very, very difficult to make a housing business work in California,” Marcil said. “Investors are leaving the state.”

He got a taste of that recently when D.R. Horton walked away from a deal with Palos Verdes. It was a gut-wrenching defeat for Marcil. The Texas-based construction giant had been poised to buy a 23-acre property with 285 town homes. The sale was in escrow, according to Marcil.

And then D.R. Horton got cold feet.

Marcil didn’t elaborate much, saying only that “they decided to leave the whole state.”

What’s clear is that D.R. Horton — the largest homebuilder in the United States by volume — saw a 10 percent drop in closings in the southwest last year, and it placed the blame for that squarely on California in its annual report.

The region currently accounts for 16 percent of the company’s national inventory, a 2 percent decline from three years ago.

It’s a signal that Marcil — steadfast Californian that he apparently is — might be onto something, politically speaking: spend less time making people with money nervous and you might get investor and developer interest to stick around.

“The problem is supply and demand,” he said. “You’ll never add supply if you keep penalizing the people already providing housing. It scares people.”