The palace on East 72nd Street and Fifth Avenue has long sat silent, its doors locked shut.

Upper East Siders and tourists pass by its grand French windows, limestone columns and wrought iron balconies.

Dry goods tycoon Henry Sloane built the house in 1896. Later, the Lycée Francais of New York moved in and stayed until selling the pair of buildings in 2002 for $26 million.

The buyer was Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani, then the emir of Qatar.

That acquisition was just the beginning for the small Persian Gulf state. In 2023, Qatar was the top foreign investor in New York City, pouring in $1 billion.

Qatar was founded in 1971 shortly after the British withdrew from the region. The peninsula spans 4,500 square miles, making it slightly smaller than the state of Connecticut. It has about 2.7 million people, a third of New York City’s population, and is the wealthiest country per capita in the world thanks to its vast natural gas resources.

The government started taking out its checkbook in the early 2000s in a bid for prestige, jockeying for influence against its rival neighbors, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

“They really want to translate their fortune into political influence and power,” one businessman expat formerly based in Doha said.

It was the start of a spree as political as it is economic. In a larger fight for power and influence, Manhattan real estate has become one of the sheikhs’ most important playing fields, even as Qatar has come to occupy a complex international position and is under increasing scrutiny from political leaders.

Billions and billions

In 2008, the country’s sovereign wealth fund made headlines when it backed Boston Properties’ purchase of the General Motors Building on Fifth Avenue, and it was around then that New York’s real estate titans began making pilgrimages to kiss the ring in Doha, especially as domestic lending dried up.

In 2014, the Qatar Investment Authority bought a 9 percent stake in Brookfield for $1.8 billion in an effort to expand its presence in U.S. real estate. Soon after, the fund set up an office at the Solow Building on West 57th Street and formed an $8.6 billion joint venture with Brookfield to develop Manhattan West.

The fund then announced that it was looking to pour $35 billion into the U.S.

“With boots on the ground, our presence in New York will anchor our interest in the region,” the QIA’s chief executive, Sheikh Abdullah bin Mohammed al-Thani, said in a statement at the time. “It is the perfect location to help strengthen our existing relationships and promote new partnerships as we continue to expand geographically, diversify our assets and seek long-term growth.”

The sovereign wealth fund is a black box, its real estate dealings hard to track. In addition to holding buildings and shares of real estate companies and trusts outright, the fund’s spinoffs and affiliates also quietly back other investors. The Real Deal spoke to brokers, investors, lenders, developers and lobbyists in an effort to paint a picture of how much of the promised investment has gone into New York. Almost all declined to speak on the record.

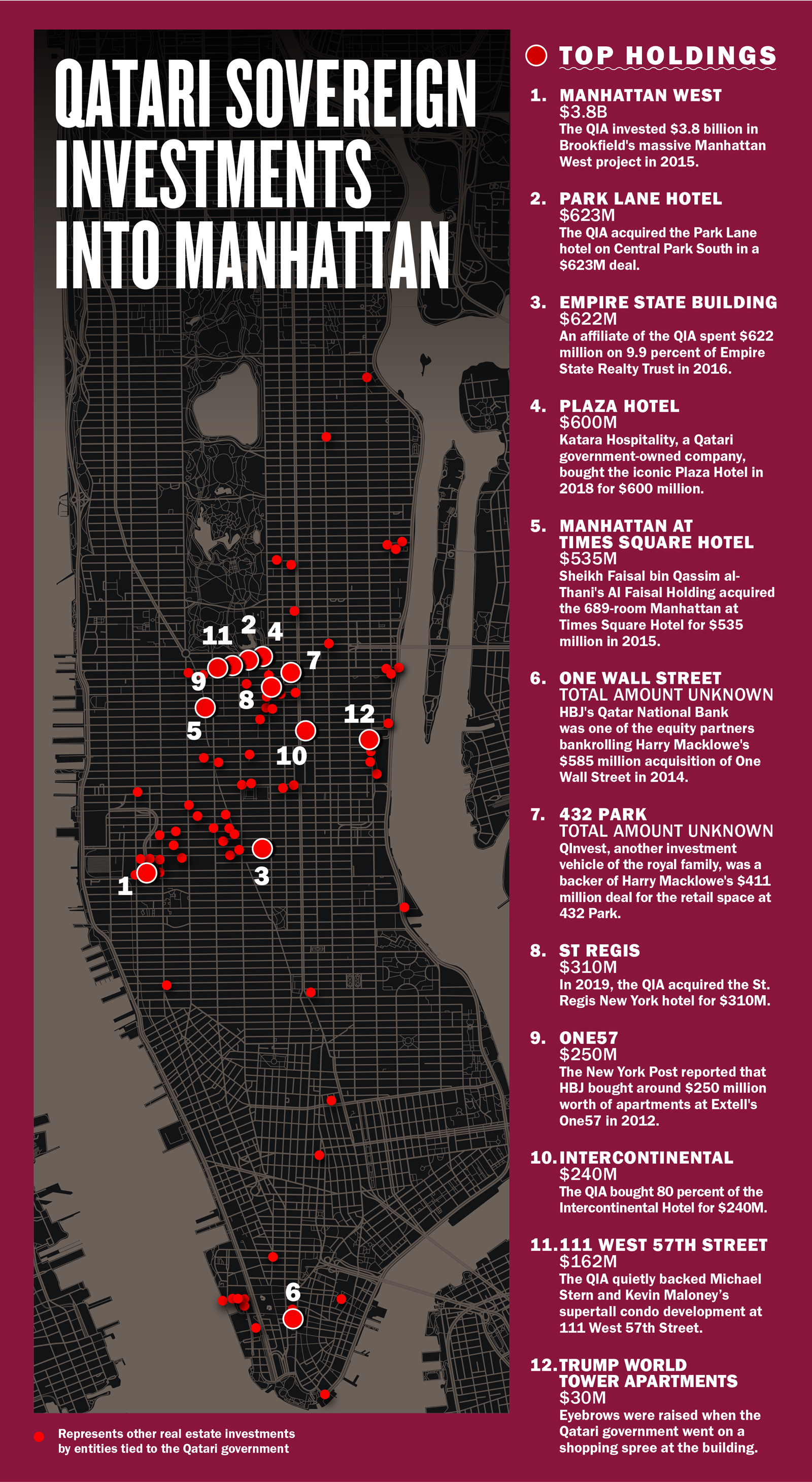

What’s clear is that 20 years after the purchase of the Lycée building, the tiny Gulf state – through its fund, related companies and royal family – has spent tens of billions on American property, amounting to an estimated 10 million square feet in Manhattan, at minimum.

“The Qataris love to buy trophy assets in very large cities, New York City, Paris and London,” said Charlie Attias, a Compass agent who leads a team focused on international buyers.

“They pick the best locations and the best assets. It’s their trademark.”

The state’s funds are largely controlled by the royal family, the al-Thanis. “It’s a very, very small shop,” said one investor who has worked with the sovereign wealth fund. “You’re talking very small.”

The QIA, a $450 billion fund, is run like a family office, numerous sources told TRD, and is deeply enmeshed with other government-owned entities. Hamad bin Jassim bin Jaber al-Thani — HBJ — managed the fund’s investments until 2013. The former prime minister and one of the world’s richest people is an “unbelievably brilliant man,” the same investor said.

After the New York office opened, the shopping increased. In 2016, the QIA acquired $622 million in shares in Empire State Realty Trust, a 9.9 percent stake.

Hospitality was the fund’s focus for a while — because, as one industry investor said, “every foreigner understands hotels.”

In 2017, HBJ bought the mortgage of the Plaza Hotel; in 2018, the hotel was bought by Katara Hospitality, a Qatari government-owned company. Katara went on to buy the Dream Downtown, while the QIA purchased the St. Regis in 2019 for $310 million. Last year, the sovereign wealth fund dropped $623 million on the Park Lane on Central Park South, acquiring it from the Witkoff Group and Abu Dhabi-based Mubadala Investment.

“They look at real estate almost like art,” said one developer who has worked closely with the QIA. He pointed to the Plaza as an example. “Even though it was losing $6 million a year, they still bought it for $600 million. It’s like a Picasso; there’s only one Plaza.”

By 2019, the QIA had invested about $30 billion in the U.S., CEO Mansour Ibrahim al-Mahmoud told reporters, and planned to raise the total to $45 billion over the next two years.

The royals seemed to land on the tarmac at Teterboro just in time — just as New York real estate market was desperate for cash.

The fund’s ambition was to “substantially increase our U.S. investments over the coming years, and our belief in the exciting long-term possibilities offered by New York City,” al-Mahmoud said in a statement in 2019, when it purchased a 45 percent stake in a $5.6 billion portfolio of Fifth Avenue and Times Square properties from Vornado in a partnership with Crown Acquisitions.

“No more business as usual”

The U.S. and Qatar have connections beyond New York trophy buildings. Qatar houses the al-Udeid Air Base, the largest American military installation in the Middle East, and has been a key U.S. ally and regional mediator, according to President Biden.

On the other hand, the country’s alleged ties to various terror groups have been thrown into the spotlight lately, with U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken telling Qatari Prime Minister Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani that “there can be no more business as usual” with terror groups. Allegations of Qatar’s financial ties to American-classified terror groups point to al-Nusra, a fundamentalist Syrian group, and Hamas, which maintains its political headquarters in Doha.

These are not the first questions about the ethics of American companies and officials working with the Qataris.

But the scrutiny hasn’t stopped the cash flow, as the state’s riyals pour into both real estate and other sectors, strengthening ties.

“Now, Qatar is no longer a payer but a player,” the former Doha expat explained. “They bought everything. Sports clubs, real estate, brands, automobile industries. Whatever they could, especially if it was a respectable brand. Porsche, Tiffany’s. It gives them access to the clients or users of those commodities. It’s always good when you can spoil people with gifts, special conditions with the assets that we are talking about.”

The Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Human Development has donated $4.7 billion to American universities, including Georgetown, Carnegie Mellon, Texas A&M and Cornell. In 2019, the QIA partnered in the purchase of Miramax Films, and in 2022 it contributed $375 million towards Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter. In health care, the Qatar Foundation has donated hundreds of millions of dollars to American hospitals and medical research centers. And in politics, officials including state attorneys general, members of Congress and mayors have gone on all-expenses-paid trips to Doha.

That a sovereign wealth fund would hide behind layers of secretive entities isn’t unique. Russian and Chinese buyers, some with shady histories, have found a receptacle for their cash in Manhattan real estate. And it’s not hard to do: According to IMF estimates, $12 trillion is hidden in empty corporate shells globally.

“You do see these countries and their wealth funds, ADIA or Mubadala in the UAE, they’re of course investing in some properties as well, but Qatar is a little bit different because of that real estate arm that they have,” said Theodore Karasik, a senior advisor to Gulf State Analytics, a D.C.-based consultancy.

“As a small state, it gives them a big reach,” he said. The reach of the Plaza, the Empire State Building, the General Motors Building, Manhattan West. “The policymakers in Doha are looking at where they want to increase their influence.”

Karasik spent a decade living in the Gulf and now advises American investors on the region.

“Everything in the Middle East is about who owns what,” Karasik said. “If you don’t understand that, you don’t understand the processes that are unfolding.”