When Charles Cohen’s team asked his lender for one last chance to stave off the consequences of an alleged $534 million default in late March, Fortress was already busy filing suit.

The billionaire head of Cohen Brothers Realty, a New York real estate scion who channeled his wealth into an indie film empire, had failed to make a scheduled $24 million payment. Cohen thought the parties had drawn up new terms that would extend his loan and defer payments, he later alleged in legal filings.

Fortress begged to differ. The lender had extended four modifications to keep Cohen afloat on a loan made in 2022, it claimed in court documents. The last was an interim measure designed to give the parties time to formulate a longer-term amendment. It would burn off Feb. 1, Fortress said, and absent a new agreement, Cohen’s payments would balloon.

The commercial real estate market has been waiting for a fallout like this. It was anyone’s guess whether it would play out so publicly.

Evidence and affirmations made under penalty of perjury shape a remarkably granular timeline of the battle between borrower and lender. They also offer a front-row seat to a major real estate player’s potential collapse.

Back in December, Cohen’s people had pledged one struggling New York office building and a design center ridden with vacancies as extra collateral for the workout. Fortress asked for the properties’ financials, but claimed Cohen’s team “dragged their feet,” for weeks, according to an affirmation by Fortress’ Randall Shy.

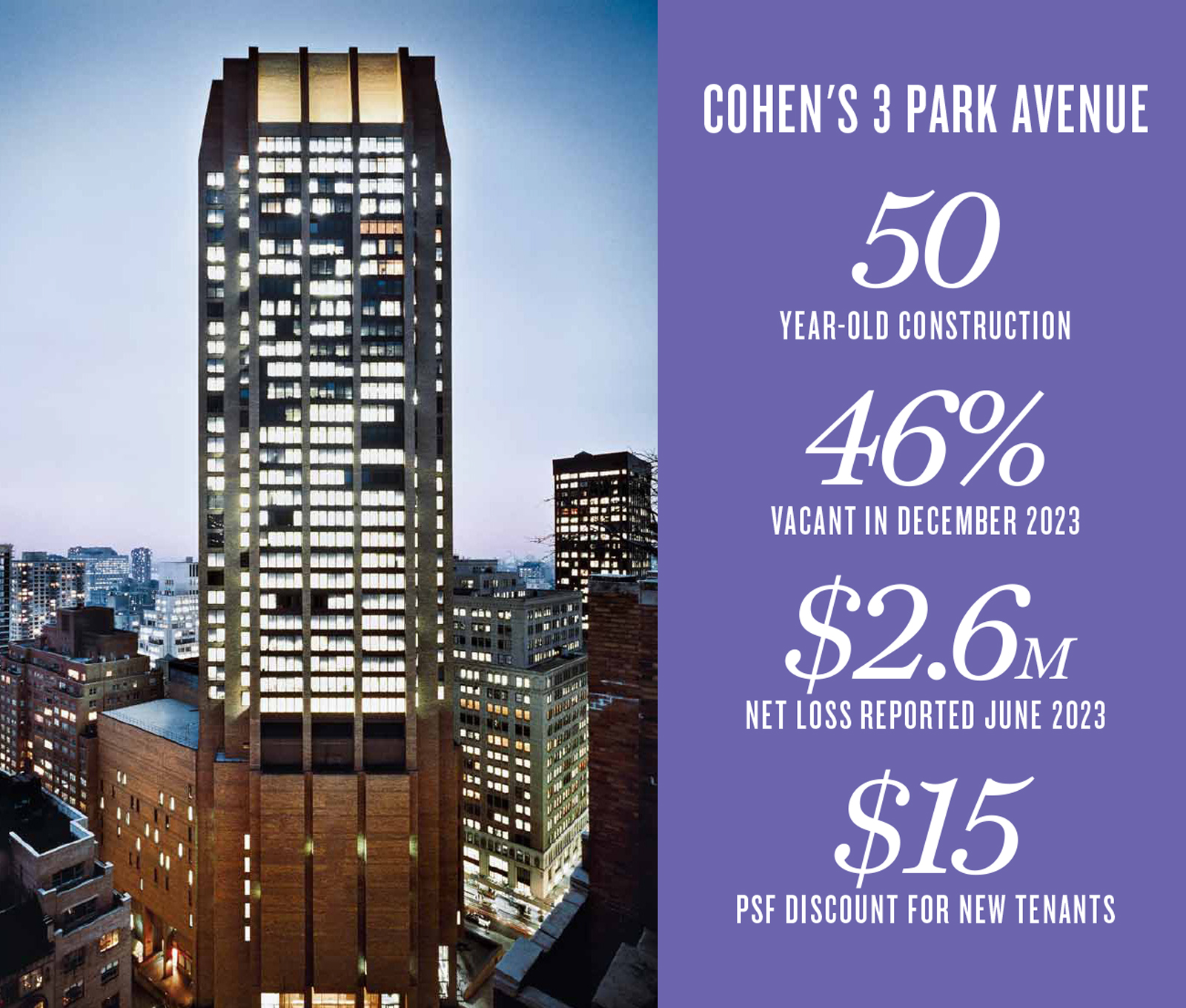

Internal financial documents included in Cohen’s affirmation point to why. The office building, 3 Park Avenue, was operating at a $2.7 million net loss in June. The Decoration & Design Building at 979 Third Avenue building reported a $4.3 million loss after debt service the same month. (It reported positive net cash flow in September.)

Even as this down cycle has worsened, industry fixtures have avoided disaster, saved by long-standing relationships with lenders willing to extend loans or defer interest. The bet: Struggling properties will recover, or owners can survive until ’25.

Cohen’s troubles could represent the end of the waiting.

On Jan. 30, Fortress had a call with Cohen and his mortgage broker Robert Horowitz. The lender said it needed better buildings to back the loan.

Cohen’s counteroffer arrived in mid-February, two weeks after his first alleged payment default and days before another. It was even less desirable. He offered to swap a 1960s office building for one of the revenue-challenged assets, as new collateral. In exchange, he wanted Fortress to waive the $187 million personal guaranty he’d signed to take out the debt, according to Shy.

The gravity still didn’t seem to register.

“You’ve not made your last payment, and you’ve not demonstrated that you understand or prioritize the severity of the situation,” Fortress’ Dean Dakolias responded.

By the last week of March, Cohen Brothers had changed its tune. It was no longer offering additional collateral but asking to hand back the keys on two pieces of existing collateral — the Design Center of the Americas (DCOTA) and Le Méridien hotel in Dania Beach, Florida — to settle the alleged default.

“There is no way for us to make the requested $24 [million] payment,” Horowitz emailed Fortress.

“My business is not a supermarket where a lender will come in and say, ‘I want this off this shelf and I want that

off that shelf.’ I run a big business.”

“None of the assets securing the … loan generate sufficient cash flow to pay debt service,” he added. “We have been funding all operating shortfalls out of pocket and are not in a position to continue to do so.”

“We do not have any choice but to work together,” Horowitz wrote in closing.

Fortress sued Cohen for payment default the same day. A month later, it filed what sources say is the largest UCC foreclosure ever.

On the line are Cohen’s interest in DCOTA and Le Méridien, a Westchester redevelopment site, a New York office building in default on its ground lease and 50 loss-making indie theaters in the U.S. and U.K., all collateral for the sponsor’s $534 million loan.

Cohen has fired back on multiple fronts, claiming Fortress manufactured the alleged default by reneging on a workout “at the 11th hour,” and filing a motion to dismiss the complaint as well as a separate suit seeking an injunction to halt the foreclosure. That filing alleges that Fortress killed his chance to refinance by throwing proceedings into hyperspeed. A UCC foreclosure bypasses the slog of a judicial foreclosure.

The auction, set for July 1, has attracted at least 140 prospective bidders, Matthew Mannion, the auctioneer, said in an affirmation.

Still, Cohen Brothers’ Chief Operating Officer Steven Cherniak said the firm “has reason to believe the foreclosure will not proceed as scheduled.”

Last month, Cohen’s distress widened. The special servicer on the $130 million CMBS loan backed by 750 Lexington Avenue, an office building he developed, filed to foreclose.

Lenders don’t make calls in a vacuum. Special servicers have their bondholders to consider. Private firms such as Fortress have their investors and their own credit lines.

Fortress’ crackdown may signal those obligations now take precedence and more foreclosures may follow. At the least, sponsors will need to put up substantial equity to restructure loans. But Cohen’s case shows even the wealthiest borrowers may not have that cash on hand and some properties are in such sore shape, even lenders won’t want them.

Office drag

Before the Fortress threat, Cohen’s distress was nearly exclusive to office.

For decades, owning office was a labor-light gig: Pay your taxes, freshen your lobbies and refinance at maturity. Since the pandemic, demand has receded, probably permanently, for Cohen Brothers’ core asset: ’70s- and ’80s-era office buildings that the landlord has failed to invest in or lease, sources say (though Cohen Brothers disputes that).

Cohen, a hands-on executive by Cherniak’s characterization, has at least $1.1 billion in distressed debt — loans either in default or with payments past due. About one-quarter of it is backed by office buildings, according to Morningstar.

“I mean, it’s happening to everybody,” said Jacob Yahiayan, founder of investment firm Continental Advisory Services and a developer who lost to Cohen on a West Palm Beach development site. “No one’s really getting out of this one alive.”

But Cohen can’t blame the office market for his alleged default with Fortress. The associated properties span five asset classes and include just one office building.

The Fortress foreclosure may be singular to Cohen.

The billionaire borrowed heavily in September 2022, after rates had jumped 2 percentage points and the Fed had signaled more to come. He signed for a loan on which interest payments would rise to 10 percent in November 2023. Meanwhile, his theater chains were crawling out of Covid, his design center recovering from an occupancy hit and his New York office building Tower 57 struggling to drum up demand, Cohen noted in a court filing.

Cohen has repeatedly boasted that he has never lost a building. If the foreclosures go through, they figure to land a one-two punch: financially painful and reputationally damaging.

“I think at a certain point this becomes not about money and a lot about ego,” said one commercial broker, speaking anonymously.

“Charlie is no exception,” the broker said. “I think he’d be embarrassed to lose these buildings, and I think that’s kind of the direction this is going in.”

The aesthete

When Cohen was growing up in the 1950s, the family firm specialized in Westchester apartment projects. By the late 1960s, Cohen Brothers had graduated to New York City office developments and set the stage for its boom years.

Cohen, who declined to be interviewed for this story, paints his childhood in suburban Westchester County without a silver spoon. It was modest; no swimming pool or country club membership. He loved film from the start, reading Variety instead of watching the Yankees.

His “entrée” into real estate, he claims in C-Suite Quarterly, was self-propelled.

“I didn’t want to be judged as someone who had something handed to them, because it wasn’t like that at all,” Cohen divulged in the 2018 interview.

Cohen attended Brooklyn Law School to become an entertainment attorney, then producer. By 1979 he was on the Cohen Brothers payroll. He bought out his father and surviving uncle in the mid-’80s and grew the family’s real estate holdings by 9 million square feet, placing the Cohen Brothers among the city’s real estate dynasties: the Rudins, Dursts and LeFraks.

He was dogged and ambitious. To construct 750 Lexington in the early ’80s, Cohen bought out rent-regulated tenants and built around one elderly holdout. Fifteen years later, he beat out competitors on Tower 57 at 135 East 57th by bumping his bid four times.

“He’s creating his own little monopoly in that area,” an insider told the Daily News of the acquisition in 1997.

Around the same time, Cohen appeared to yearn for more.

He started with design. “Always” interested in the subject, as he once told the New York Times, he bought showrooms in New York then Los Angeles, recasting Cohen Brothers’ office-heavy portfolio through the lens of an aesthete.

“It was a nice change of pace,” he said of his first design center: the Decoration & Design Building.

In the aughts, Cohen took a career-defining leap into the arts. He pumped $300,000 into the 2008 feature film “Frozen River.” Financially, the bet was bad, but the movie nabbed two Oscar nominations.

“It gave him the feeling that he could do this,” his wife, Clo, told the Jewish Journal.

Cohen self-funded film distributor Cohen Media Group and “had the pleasure of losing more money,” according to an Associated Press interview. He bought, then revamped the shuttered Quad Cinema in New York, reopening it in 2017. “It’s not about making a fortune,” Cohen told IndieWire.

He then acquired Landmark Theatres in December 2018 and art house chain Curzon the following year. Curzon had U.K. distribution rights to “Parasite” and started screenings the weekend of the 2020 Academy Awards. The film won Best Picture, with Cohen in attendance.

“I’m a little kid from New York,” Cohen said of an earlier red carpet appearance. “I’m rubbing shoulders with celebrities.”

Despite the early hiccups, Cherniak said those ventures have “long-standing and increasing value.”

Yet Landmark and Curzon each reported multimillion-dollar losses in 2023, and Curzon projected even greater ones in 2024, a Horowitz email to Fortress showed.

Offstage, the steady real estate business had been wobbling, too.

Market or maker

Cohen had wrapped development on the Red Building in West Hollywood, a piece of the Pacific Design Center and home to Cohen’s West Coast office, in 2013.

In 2019, revenue could barely cover payments on the building’s $196 million fixed-rate loan, Morningstar shows. In Manhattan, 750 Lexington reported occupancy of about 80 percent the same year, and over half of the office space at 222 East 59th Street was vacant.

Then came the pandemic, serving what would become a permanent blow to office buildings and a critical hit to Cohen’s other assets: movie theaters, design centers and a hotel.

By summer 2020, Cohen was delinquent on $332 million in office debt backed by 3 Park Avenue and 805 Third Avenue, a project that helped shape its Midtown strip in the early 1980s. He fell behind on the $165 million loan backed by the Decoration & Design Building.

The Red Building in West Hollywood was bleeding.

Commercial brokers say his troubles weren’t just market-made: He has invested little in renovations and is a notoriously difficult landlord.

“He is the biggest pain in the ass,” said one anonymous broker. “He lures tenants into buildings by offering very aggressive low rents and then nickels-and-dimes them for every little thing.”

“Any reputable broker would really think long and hard before bringing a tenant to a Cohen building,” said another broker who requested anonymity for fear of retribution. “He treats brokers horribly and tenants horribly.”

Cherniak said the firm prides itself on high tenant retention and a willingness to “work through their challenges,” adding that Cohen Brothers “do[es] not nickel-and-dime anyone.”

“We continually invest and reinvest many millions of dollars each year in our buildings,” he said, noting that Cohen Brothers is revamping the lobby of 622 Third Avenue, an office building, and recently wrapped renovations to 3 Park Avenue’s entrance and lobby — both multimillion-dollar projects. Other updates include updated elevators, HVAC systems and “beautification.”

Pre-Covid, those investments might have been sufficient to draw tenants. But high-paying lessees now demand amenities, outdoor space and, in some cases, custom-built offices. About half of 3 Park is vacant, though Cohen became current on its loan this year.

Occupancy across Cohen office properties for which data is publicly available averaged 66 percent at the end of 2023, according to Morningstar.

Horowitz, who has arranged financing for Cohen for two decades, disputes the notion that Cohen’s portfolio is subpar.

“The office market is a little soft, it’s challenging,” said Horowitz. “But I think the assets he owns are good buildings that tenants will come to.”

Cohen Brothers financials show three office properties — 750 Lexington, 3 Park Avenue and 805 Third Avenue — and the Decoration & Design Building operated at multimillion-dollar deficits last June.

Horowitz said outside of the dispute over 750 Lexington and Fortress, “the balance of the portfolio is strong.” The portfolio is not overleveraged, he said, and Cohen Brothers has “substantial equity” in the buildings.

He added that Cohen “will prevail” in his dispute with Fortress.

Other properties, meanwhile, were literally underwater.

Saks Fifth Avenue, the retail tenant at 135 East 57th Avenue, said Cohen had failed to fix leaks that had flooded its store for six years, according to a recent suit, and the store was “forced to resort to placing plastic buckets to collect the water.” Cohen sued to eject Saks over withheld rent the day after the retailer filed suit, then filed a second suit alleging it breached its guaranty.

Multiple complaints point to a similar pattern of negligence. Numerous contractors claim Cohen stiffed them, a personal driver alleged he was denied overtime pay, and a partner in Cohen’s Roosevelt Island apartment development sued, claiming unpaid distributions.

Cherniak said lawsuits are common in the course of business and that the firm has settled many suits “to mutual satisfaction.”

“There are some claims that are unfounded, frivolous or merely asserted to try to take advantage of our businesses,” said Cherniak.

Even on projects related to the arts, sources said Cohen shows frugality and overconfidence.

After tenants fled DCOTA, the Florida design center, in 2019, The Real Deal asked Cohen if he would consider dropping rents.

“No, I think the rents we charge are fair,” he replied. The “warehouse-type buildings” those tenants were seeking out instead “are not the quality that DCOTA is.” Cherniak echoed that Cohen Brothers doesn’t “lease to tenants who would dilute the prestige and value” of its design showrooms.

Those claims came after Fortress had saved Cohen from a $173 million foreclosure by making a loan later folded into the $534 million debt.

War of attention

When negotiations with Fortress were heating up, Cohen was in Paris taking meetings with the French government over an office project, then checking in on his renovation of La Pagode theater. (An oenophile, he also owns a Saint-Tropez vineyard.) He hopped the Channel to scout tenants for Curzon theaters in London, where his holdings also include luxury retailers Harrys London and Richard James.

His adversaries in the foreclosure fight were probably at the office.

Cherniak stressed that Cohen is “always available — 24/7 — whether in the office or traveling on business.”

“He is a hands-on executive” who approves and signs “every contract … every lease and virtually every check,” the COO said.

Shy’s affirmation shows workout discussions mostly took place with Cohen Brothers executives. On the call Cohen joined two days before his first alleged default, the CEO was “quiet” and “simply informed Fortress that [his firm] would go back and discuss internally before proposing new terms.”

“We have been funding all operating shortfalls out of pocket and are not in a position to continue to do so.”

When Cohen spoke with Fortress executives weeks after the alleged default, his tone carried the airiness of someone who had never faced real consequences: “Over the last 20-plus years, we have always found a way forward together.”

Fortress is sometimes known as a lender of last resort, game to make large complicated loans at high interest rates and just as willing to seize collateral should payments cease.

Just ask Kent Swig or Harry Macklowe. Fortress nabbed a Swig rental tower for one-eighth of its value at foreclosure, and on a Macklowe deal charged the investor 15 percent interest and demanded a personal guaranty.

On the Cohen loan, Fortress is pursuing the billionaire personally on a $187 million guaranty, a hit that would compound the real estate losses.

Fortress executive Steve Stuart said the firm never plans to take title despite a hardball reputation.

“We make a loan, we’re expecting to get paid back,” Stuart said at TRD’s New York Forum in May. “We’re not expecting to own the property; that is literally a last resort.” Stuart declined to comment on negotiations with Cohen.

Bringing in new tenants for Cohen’s office and retail would take a staggering amount of money and effort, and it’s unclear how much Fortress could recoup through asset sales.

The parties’ grueling back-and-forth before the foreclosure and the multiple chances afforded Cohen to propose better terms imply that the lender would prefer a workout.

But the exasperation executives show in later emails and the firm’s unwillingness to take Cohen’s final offer — some of his assets — signal that Fortress’ patience may have run its course. Cohen has also been steadfast in refusing to provide particular assets as collateral.

“My business is not a supermarket where a lender will come in and say, ‘I want this off this shelf and I want that off that shelf.’ I run a big business,” he said in a deposition .

If Cohen can cut a deal with his lender, he may have to pump equity into assets, under tremendous pressure. But Shy’s affirmation signals Cohen’s “personal financial situation” may not allow for it.

If Cohen loses the assets, we’ll know the lenders are serious — a frightening prospect for a market in the throes of the worst down cycle since the Great Financial Crisis.

Closing credits

In mid-May, Cohen filed papers to convert the upper floors of 623 Fifth Avenue, built in 1988, to residences.

Conversions are tricky — many buildings, particularly ’80s-era offices, are too big, vacancy has to be high enough, and construction financing remains a challenge. But owners of aging offices have few options. Renovating is expensive, and lowering rents unappealing.

Cohen already tried and failed on one conversion play. Last year, he defaulted on his ground lease at Tower 57 after he allegedly failed to pay $9 million in rent. He had asked his landlord to convert the building, which struggled with “substantial vacancy,” Cohen wrote in an email. But the land owner, William Wallace, refused.

Cohen, in response, moved to surrender the building. The suit is ongoing.

Regardless of which recovery routes Cohen chooses, the complexity of the remedies will require his undivided attention.

In early May, a spokesperson for Cohen said the owner was unavailable to comment because he was again in Europe. Ship tracker MarineTraffic showed Cohen’s yacht, Seasense, moored in Genoa, Italy, alongside the yachts of billionaires Larry Page, co-founder of Google, and Ann Kroenke, Walmart heiress. Cherniak specified it was there for maintenance purposes.

Despite Cherniak’s claims that the source of Cohen’s net worth is “irrelevant,” much of it is tied to his real estate holdings, according to Variety.

If Cohen fails to work things out with Fortress or shore up the loans in alleged default or distress, his wealth, and therefore status, could hang in the balance.

By Cohen’s estimation, Fortress’ actions have already caused a potential “$1 billion in damages across my entire building portfolio.”

Cherniak stressed that the firm does not intend to lose any assets.

“We are not concerned,” he said. “Perhaps the newspapers are more concerned.”

Regardless of how Cohen’s plight plays out, the saga suggests that the laissez-faire asset management of the old guard is no longer an option. Even the biggest players must make a choice: Focus or face the music.