On a recent early-morning flight to New Orleans, a flight attendant with an acute sense of comedic timing landed a zinger: “I am looking to sell a house, can anyone assist me?”

The joke was met with immediate laughs from a group of Keller Williams agents, some in matching T-shirts, others carrying swag adorned with the company’s bright red logo — all headed to the firm’s annual “Family Reunion.”

At this year’s mid-February conference, 17,000 agents and franchise owners descended on the New Orleans Convention Center, which had the feel of a giant homecoming party complete with brass music blaring and performers walking around on stilts.

By the time company co-founder Gary Keller emerged onstage — to AC/DC’s “Back in Black” — the crowd had been whipped into a frenzy.

But behind the festivities, the national franchise brokerage has been grappling with some hard realities, including aggressive poaching and an urgent need to keep pace with tech companies trying to bring real estate out of the dark ages.

Keller Williams is still the biggest franchise brokerage in the U.S. and Canada, with more than 159,000 agents. (According to the National Association of Realtors, Coldwell Banker is No. 2 with 89,000 agents, followed by Re/Max with 62,441.)

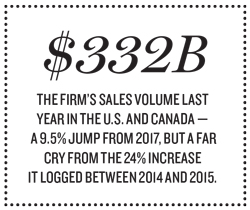

But it’s been increasingly difficult to maintain aggressive growth — both in terms of agent headcount and transactions. Last year, the firm’s sales volume hit $332.4 billion in the U.S. and Canada — a 9.5 percent jump from 2017, but a far cry from the 24 percent growth it logged between 2014 and 2015.

And its model has struggled to gain traction in urban markets like New York and Los Angeles, where most of its agents don’t play in the high end.

In addition, the firm saw a leadership shakeup in January when Keller seized full control of the company, replacing CEO John Davis, a company veteran who served two years in the post.

“It’s just kind of interesting to me that they’ve gone through three CEOs in the past five years,” said Steve Murray, founder of the research firm Real Trends, who sat in the front row during Keller’s keynote address in New Orleans.

Despite Keller’s three-hour update on the firm’s $1 billion tech push, Murray noted, “He glossed over the fact that for the first time in 12 years, the company didn’t grow.”

An evangelical leader

Gary Keller has something of a cult following within the Keller Williams universe.

A Texas native and son of schoolteachers, Keller grew up dreaming of becoming a musician. But after graduating Baylor University in 1979, he moved to Austin and got into real estate. In 1983, Keller and Joe Williams borrowed $44,000 and launched their firm out of a one-room office.

Their growth was swift.

Within two years, Keller Williams — which started with and still maintains “core values” of God, family and then business — was the No. 1 firm in Austin, and it quickly expanded throughout the state.

Though a millionaire many times over, Keller doesn’t live a flashy lifestyle of private jets and L.A. mansions. He and his wife, Mary, live in an 8,400-square-foot house in Austin that they bought nearly two decades ago.

Onstage in New Orleans, the 62-year-old wore his preferred uniform of black jeans, a Keller Williams shirt and an Apple watch. And he managed to channel both Steve Jobs and the average Joe, mentioning that he was (once upon a time) a broke agent who borrowed $500 from his dad. As he laid out lofty goals for the company, he peppered his speech with aphorisms like “I do not fear physical failure. Failure leads to growth.”

For many agents, Keller’s teachings (he’s written three best-selling real estate books) are the backbone of the brokerage, which is known throughout the industry for its intensive training programs.

Lately, Keller’s charisma has given KW fans confidence that he can steer the company through these increasingly tumultuous times in the residential brokerage business.

“It’s like Steve Jobs coming back to Apple. We’re all behind him,” said David Osborn, one of the largest Keller Williams franchise owners in the country. “You’d be a fool to underestimate Gary Keller.”

Abe Shreve — who joined Keller Williams in 2006 as an agent before becoming a team leader and then an agent coach — said Keller is the right person to be leading the firm through this time of digital warfare.

“Google and Amazon and Zillow are all getting into the real estate business. When they can, they’ll cut out the agent. Gary sees that. He fights for us,” said Shreve.

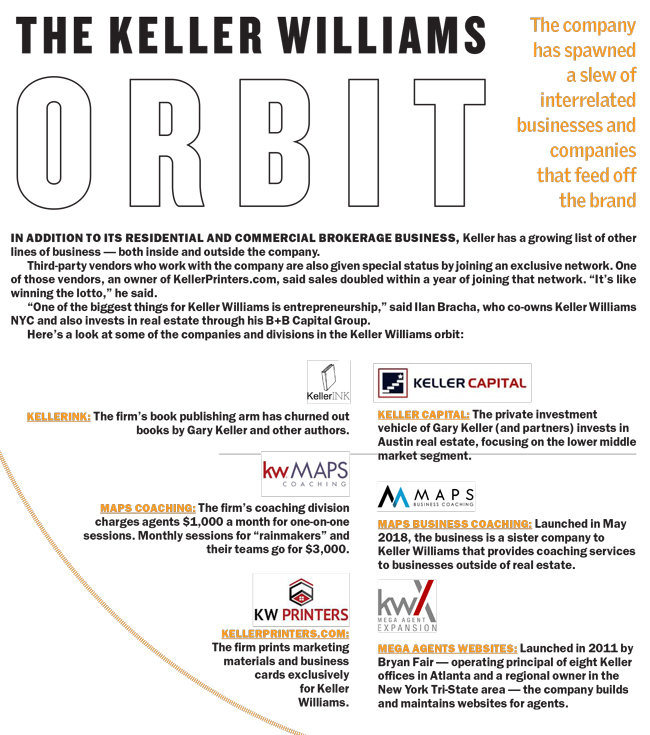

Shreve, who launched a sister company called MAPS Business Coaching for Keller Williams last year, is one of many who has benefited from the firm’s entrepreneurial ethos. Keller Williams is involved in a string of nonbrokerage businesses both within and outside the company.

Osborn — who began as an agent — claims to have started 35 real estate-related businesses. Within Keller Williams, he is an investor in five regional franchises, which have offices in California, Texas, New Mexico, Florida, Virginia and Canada. He also owns 15 market centers, or individual offices.

Osborn compared Keller’s training to getting an MBA. “I think it’s a passport to a career for some agents,” he said.

Scaling up — fast

Keller Williams has been in growth mode from the start.

For years, it’s differentiated itself through a system that rewards agents with a portion of the profits generated by their office for bringing in new recruits.

To date, the brokerage says, it’s doled out $1 billion to agents through that program.

Keller Williams was also an early adopter of agent teams, which it embraced in the ’80s as a way of making top agents more productive.

“Keller Williams was able to attract the top talent because of its embrace of teams,” said Rob Hahn, founder of real estate consulting firm 7DS Associates. “When Re/Max was debating whether they wanted teams, Keller Williams was out there recruiting them.”

Four years ago, the company took it a step further when it introduced “expansion teams,” encouraging top agents to hire brokers in new markets. (For example, a top Texas-based agent can now do deals in L.A. by partnering with local agents.)

While its profit-sharing model fueled recruitment in the 1980s, Keller’s next big growth spurt came in the 1990s when it began selling franchises outside of Texas.

In general, franchise business models like Keller and Berkshire Hathaway’s HomeServices of America — which did $136 billion in sales with 44,000 agents last year compared to KW’s $332.4 billion — are designed to scale up quickly.

By selling franchises, the corporate office can build 10 to 20 offices at a time.

For those looking to own one of those offices, joining Keller Williams as a franchisee requires an initial $35,000 plus 6 percent of gross revenue.

The firm also has a unique decision-making structure.

Unlike bureaucracies that have a top-down approach, Keller Williams gives its most productive agents a say in corporate decisions. For example, “mega agents” are invited to participate in “mastermind” groups that advise company executives on various initiatives.

The model has attracted attention beyond real estate.

In 2015, Stanford University business professor David Larcker wrote that part of the success of Keller Williams is that it “willingly cedes significant decision-making authority to its associates and relies on culture to ensure that its operating model and people are successful.”

KW does LA & NYC

But Keller Williams’ plug-and-play model isn’t foolproof.

Historically, national brands have struggled to crack the insular world of New York brokerage in the absence of a local multiple listing system.

Paul Morris, CEO of Forward Management, Keller’s biggest L.A. franchise

And in California, Keller’s high-commission model — which initially attracted agents — has lost luster in recent years as average commission payouts have risen.

“In 2004 and 2005, an 80 percent split was a very big deal in L.A. Now, getting 75 percent to 85 percent is very normal,” said Michael Nourmand, president of the brokerage Nourmand & Associates, which has offices in Beverly Hills, Hollywood and Brentwood. “Why would you go there?”

Some also think Keller’s relentless recruiting has taken a toll on agent quality.

“I think [Keller Williams Reality International] set unfair targets and unrealistic targets,” said Spencer Krull, the general manager of Westside Estate Agency in Beverly Hills, who was a training director at Keller Williams in Santa Monica between 2016 and 2018. “That led to bringing in agents who were less than stellar.”

Keller Williams’ Forward Management franchise in L.A., in fact, held the dubious honor of having the highest agent turnover of any firm in the county between January and August of last year. During that stretch, its seven L.A. offices lost 384 agents and gained 312, according to an analysis by The Real Deal.

“Even with our top-quality training, the industry, by nature, has high attrition rates,” Paul Morris, CEO of Forward Management, told TRD in October.

In total, Forward Management — which is the company’s biggest franchise in L.A. — saw its year-over-year dollar volume in 2018 drop by 10 percent to $5.5 billion in Southern and Central California, according to Real Trends. It also saw a nearly 20 percent drop in the number of transactions it did.

On the East Coast, the company’s New York City franchise, which launched in 2011, has been wracked with financial trouble, an exodus of agents and leadership tumult.

And in April 2018, KWRI sent a letter of default to the franchise’s Midtown office — one of two offices in Manhattan — citing an “alarming number of questions and concerns about the leadership and viability of the market center.”

Ilan Bracha, who owns the NYC offices with a partner, declined to comment on the letter from KWRI, but he said the Midtown office is “doing great” under its interim leader.

Either way, it’s not just New York and L.A. that are facing headwinds.

Nationally, Keller Williams’ model has been under attack, too.

In March, the company was forced to slash nearly 11,000 “ghost” agents from its rosters after news reports that the firm kept inactive agents on the books to inflate its headcount. The incident didn’t come as a surprise to everyone; observers said the practice was the industry’s worst-kept secret.

And for years, critics have tried to poke holes in Keller’s profit-sharing system — calling it a multilevel marketing gimmick. “If profitability is squeezed, payouts go down,” said one brokerage CEO.

But by and large, agents have rejected those claims. “The agents love it,” said 7DS’ Hahn. “Some of them make a lot of money from it.”

While Keller Williams is facing all of the pressures other traditional brokerages are seeing, its biggest threat has come from eXp Realty, a fast-growing national virtual brokerage that also gives agents profit-sharing — plus stock options.

After going public last May, eXp saw its market cap soar to $1 billion, and last year the company’s revenue skyrocketed 220 percent to $500.1 million.

And it’s snagging agents, too: Between December 2017 and 2018, eXp increased its headcount 139 percent to 15,570 agents, and by the end of this past February that number grew another 1,500-plus.

Many brokers see eXp as a new and improved version of Keller Williams. And though it’s difficult to quantify, the virtual firm has been aggressively poaching from its ranks.

Last year, eXp tapped Dave Conord — a top recruiter at Keller Williams — to lead its American expansion. And an Arizona-based team called Group 46:10, which has 50 agents in four states, defected to eXp.

David Devoe, a New Jersey-based agent who led one of Keller’s biggest teams until recently, said eXp’s economics are too good to ignore. Since he swapped firms, he said, his monthly profit share has increased 20-fold. “Once you see eXp,” Devoe said, “you can’t unsee it.”

The tech conundrum

To catch up with eXp — and surge past a wave of innovation threatening traditional brokerages — Gary Keller declared in 2017 that his firm was no longer a real estate company.

“We are a technology company,” he said at Family Reunion that year. Not long after, Keller Williams announced its $1 billion plan to build out its own tech platform.

In New Orleans in February, he devoted several hours onstage to explaining the firm’s suite of new tools like Command (a CRM hub) and Connect (where agents and teams communicate internally).

He was also eager to showcase the work of Keller Labs, an R&D forum that worked with 27,000 agents across the company to develop the firm’s new tools.

Their research showed that in 2018, Keller agents collectively shelled out $1 billion to cover costs connected to the existing patchwork of tech tools. “That number shocked us,” Keller said. “Our goal is to replace that money for you.”

He acknowledged his skeptics: “We had to build a platform,” he said. “In the process of doing that, you look stupid because you don’t have anything. But you are building it.”

To vouch for the process, Philadelphia agent Mike McCann joined Keller onstage. McCann, a top Berkshire Hathaway agent for decades who closed $365 million in deals last year, jumped to Keller in January with his 25-person team.

“The acceleration of change in the industry isn’t like anything I’ve seen. I’m here to embrace the new world,” he said.

In one sense, Keller Williams is trying to beat its rivals at their own game. Last year, the company tried (unsuccessfully) to buy a virtual world company later snapped up by eXp. Keller Williams President Josh Team has also said the company is watching Redfin because it thinks it can “copy the technology of Redfin before Redfin can take the market share.”

But some of the industry’s biggest players have rejected Keller’s approach.

Last year, Realogy CEO Ryan Schneider steered that brokerage conglomerate away from creating, delivering and maintaining all of its tech.

Instead, the New Jersey-based company — whose NRT division operates the Corcoran Group, Coldwell Banker and Century 21— is combining proprietary tools with existing third-party tools that agents already use.

Now, the company is more strategic about where it allocates time and resources, said NRT CEO Ryan Gorman. For example, he said, creating a CRM from scratch isn’t worth it, because “to create a product that is so good that a successful agent who’s happy with their current tool will change to use ours is a very, very high bar.”

“We focus on what’s necessary,” he said. “If it exists, we use it. If it doesn’t, we build it.”

Real Trends’ Murray said that unlike public brokerages such as Realogy, Keller Williams is well positioned to pivot quickly because it is not beholden to shareholders.

“Gary has redirected tens of millions of dollars — because he can,” he said. “It’s his company.”

Within Keller’s ranks, there is widespread support for the tech investment.

Charles Olson, the owner of Brooklyn-based Keller Williams Realty Empire, said the company’s tech is already paying off for him: Recently, an agent in Florida connected him with a client looking to sell her $5 million Brooklyn townhouse.

Despite his faith in Keller’s leadership, Murray has doubts as to whether betting heavily on technology pays off for brokerages in general.

His own research shows two-thirds of consumers choose an agent because of a personal connection.

“It’s almost like a zero-sum game. Every one of them has to build something,” he said. “But if they think that’s the panacea to growth, I have a big question about that still.”

Osborn, the franchise owner, said he’s seen Keller reinvent his brokerage model many times over, adding mortgage, coaching and publishing to stay competitive.

“You’d be a fool to underestimate Gary Keller,” he said. “I’ve seen him pivot before many times.”