Developers plotting to build in the hot Los Angeles market are bracing for tighter lending conditions, even for projects backed by robust supply-demand fundamentals.

Banks, the traditional source of construction financing, are in retreat due to a more conservative lending approach and new pressure from regulators. Developers who do secure bank loans have been required to put up more equity, accept higher borrowing rates and provide stronger guarantors, industry insiders tell The Real Deal. Builders have also found nonrecourse loans from banks to be elusive in this more cautious environment.

“Construction lending is much more difficult than it was last year,” said Chris Casey, an L.A.-based managing director in JLL’s real estate investment banking group.

“Banks are getting a lot more scrutiny from regulators about how they’re underwriting loans, and the risks they’re taking. When you have someone breathing down your neck, you want to be very cautious about your lending,” he said.

This has created an opening for new players such as debt funds, which have emerged as alternative sources of capital, as well as for foreign money that increasingly sees U.S. real estate as a safe haven amid global volatility.

“In the past 12 months, we’ve seen the proliferation of debt funds come into this space. They are serving a very critical role as a viable alternative,” said David Milestone, managing director at commercial brokerage Newmark Grubb Knight Frank.

However, banks continue to finance the bulk of the L.A. market’s frenzy of development. Construction is largely backstopped by big banks such as Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Deutsche Bank, Citigroup and Union Bank. Arkansas-based Bank of the Ozarks is also a major player, especially because it offers a nonrecourse construction loan program that doesn’t require a full repayment guarantee, according to real estate professionals.

However, while banks used to be comfortable providing leverage of up to 70 percent of the total cost of construction, current loans max out around 50 percent or 60 percent. Lenders are requiring more capital, partially because bankers are concerned about how much longer the real estate boom will last.

“The market has shifted to where lenders are trying to find reasons not to do deals. Before, there was a focus on the strengths. Now, weaknesses are focused on,” said Jake Roberts, senior vice president for capital markets in Marcus & Millichap Capital’s West L.A. office.

“Everyone is worried: Are we near the end of the run-up here?” Roberts said.

Tougher regulations

Beyond that more conservative approach to lending is the tougher regulatory environment banks are grappling with. Not only are real estate loans and single-asset exposures being more closely scrutinized, but looming new regulation rules are also forcing lenders to become more cautious.

Specifically, banks are trying to get ahead of new regulation concerning “high volatility commercial real estate,” known as HVCRE. These new rules, aimed at lessening the risk of the growing amount of construction loans on banks’ balance sheets, require lenders to set aside more capital and adhere to tighter underwriting standards for certain risky loans.

“Banks are really getting hit with regulations that impact the pricing and risk tolerance relative to construction loans,” said Val Achtemeier, vice president for debt and structured finance at CBRE Capital Markets in Los Angeles.

“Banks are really getting hit with regulations that impact the pricing and risk tolerance relative to construction loans,” said Val Achtemeier, vice president for debt and structured finance at CBRE Capital Markets in Los Angeles.

In practice, this means developers are having more difficulty securing financing from banks at the right price, under the right conditions. Real estate executives say bank loans now carry higher rates, require greater equity and more guarantors with higher net worth, as well as enhanced liquidity.

Banks have also sought to minimize their exposure to any one property by limiting loan sizes to around $30 million. That requires syndicating loans among several banks for larger deals, increasing the execution risk and complexity.

“In general, you’re seeing construction loans at the major banks being reserved for their best clients and for projects that have very strong supply-and-demand levels,” said Achtemeier. “Traditional banks are being more conservative in construction loans, even with top sponsorship.”

The ability to secure financing at favorable interest rates can often hinge on the property type. NGKF’s Milestone said apartments “get the most-favored-nation treatment” in the L.A. region because of strong demand. Office, industrial and retail developments are also looked upon favorably, especially if landlords have already lined up tenants. Experts say that pre-leasing can be a critical factor in obtaining financing for these projects.

Hotel development can be much more challenging to find financing for, Milestone said, because they are inherently riskier assets.

Residential condominiums are also seen as risky, especially those that require units to be sold at the top of the market. “Condos are on the no-go list for a lot of people. We saw what can happen to condos in the last go-around,” said Ron Bonneau, senior vice president in the L.A. office of debt fund PCCP.

Debt funds step in

Condo development is where debt funds are seeing a lot of opportunity. They have been able to capitalize on the bank retrenchment by providing loans to condo projects as well as other developments traditional lenders are now shying away from.

PCCP provided more than $70 million in financing to support the construction of 1050 South Grand, which will be one of Downtown L.A.’s first brand-new luxury residential properties in the past decade. Marketed as “TEN50” and developed by San Francisco-based Trumark Urban, the 25-story property is nearing completion and is currently selling luxury condos that start in the low $600,000 range.

Like other debt funds, PCCP doesn’t face the same regulatory constraints as banks. That allowed the firm to avoid syndicating the loan and cover nearly 70 percent of the cost of the development, a level of leverage that banks don’t typically underwrite these days. PCCP also provided a nonrecourse loan for TEN50.

Bonneau said those leverage levels and the nonrecourse structure are common for debt funds. “Most banks need recourse. But debt funds are more comfortable without recourse because they are getting compensated for the risk,” he said.

How much compensation? Bonneau said pricing varies, but generally condo project loans financed by debt funds carry floating rates that are priced around five percentage points above Libor (the benchmark interest rate for short-term loans many banks use), if not more. That’s great for yield-hungry debt funds that are struggling to hit their required returns in today’s world of extremely low interest rates.

Beyond PCCP, there are around 30 or 40 active debt funds, including ones operated by ACORE Capital, Starwood, Blackstone, Mesa West Capital and Cornerstone.

“That debt-funds base is definitely serving a very critical role as a viable alternative,” said JLL’s Casey.

Cornerstone was an early mover in the debt-fund space in L.A. The firm said its commercial mortgage group has financed more than $1 billion in core mortgages on non-transitional assets in the L.A. area since 2013. That includes a wide range of properties, spanning hotels, condos, office, retail, multifamily and even industrial.

“The addition and growing prevalence of debt-fund capital is more or less a reaction to a funding gap,” said John Gerber, vice president for alternative investments at Cornerstone.

Cornerstone helped bankroll the construction of the West Hollywood Edition, a new luxury hotel and condo development at Doheny Drive and Sunset Boulevard. More recently, Cornerstone provided acquisition and renovation financing for the Burbank Town Center, a 1.2 million-square-foot shopping mall in downtown Burbank.

“We expect the trend of debt-fund growth to continue for some time as new banking regulations continue to take hold,” said Gerber.

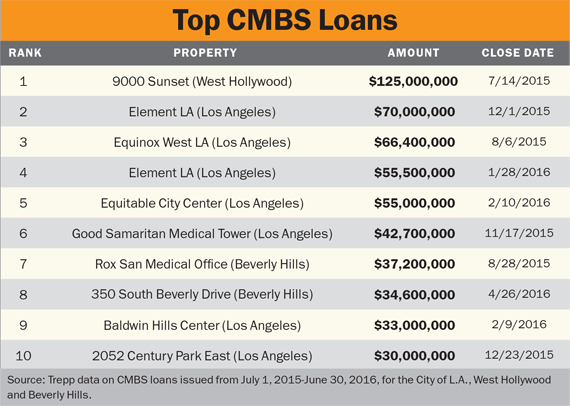

New developments don’t typically rely on the commercial mortgage-backed securities market, a type of financing more commonly used for refinancing and acquisitions of existing properties. The CMBS market, as it’s known to do, has experienced pockets of volatility over the past year, due to various economic and political shocks.

“CMBS is still soft,” said Roberts. “You’re a little nervous going into any CMBS deal,

because between when you sign up and when you close, the market can shift and your terms can change a lot. Before, they were the go-to. Now they have their place.”

Foreign investors fill the gap

In part due to global volatility, premier American real estate markets such as L.A. have enjoyed an influx of foreign capital, especially for larger development deals.

Downtown L.A.’s biggest project under construction is Metropolis, which is being developed by China’s Greenland USA. The 2-million-square-foot development will include a hotel and condos. The second-largest project is the soon-to-open Wilshire Grand. The 1.7-million-square-foot mixed-use building is being developed by Korean Air.

Another of DTLA’s largest projects is being developed by China’s Oceanwide Real Estate Group, and is being paid for with mostly or all cash. Known as Oceanwide Plaza, the $1 billion mixed-use development, which is set for completion in late 2018, will feature condos and hotel rooms spanning a 49-story tower and two 40-story buildings.

Expect the foreign capital influx in L.A. to continue, especially in the wake of the Brexit referendum in the U.K., a shock that has already disrupted the previously hot London real estate market.

“None of us like to see global volatility — and it does impact our stock and debt markets — but our core U.S. real estate investments are viewed as a safe haven with some yield,” said CBRE’s Achtemeier. That’s one of the reasons she and others are optimistic about the prospects of the L.A. real estate market, despite concerns about how much longer the expansion will last.

Milestone pointed to a range of positive drivers, including low interest rates, low inflation, limited pockets of oversupply and leasing velocity.

“I’m fairly bullish about where we’re headed over the next 12 to 24 months,” he said.