The tipping point for Greenbrook Partners came in late 2022.

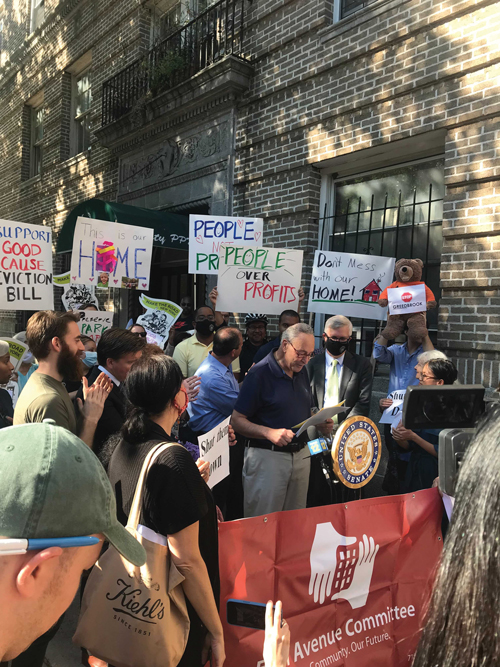

The New York City multifamily developer and investment firm was coming off a rough stretch. Tenants had protested orders to vacate, prompting Sen. Chuck Schumer to call the firm’s action “illegal” (it wasn’t).

Greenbrook was getting sued by New York City over housing violations and by tenants claiming their apartments had been unlawfully removed from rent stabilization. The state attorney general had opened an investigation into allegations of tenant harassment. And left-wing publication Mother Jones piled on with a 5,000-word piece branding Greenbrook and its private equity partner Carlyle Group “real estate predators.”

The attention figured to put a target on the back of Greenbrook founder Gregory Fournier. But as rapidly as the media circus assembled, it disappeared.

In October 2022, Greenbrook settled with the state for a modest sum, then vanished from the press.

At the same time, Fournier was pulling off a subtle strategy pivot, trading out acquisitions of the bigger rent-stabilized product that sparked tenant pushback for value-add deals with fewer complications.

Property records and broker interviews indicate his focus has shifted to buildings primed for removal from rent regulation and to small-fry rental properties with potential for serious rent growth.

Low profile, high places

Through the controversies of 2021, Fournier maintained as low a profile as he could manage, evading or declining requests for comment. He remains staunchly press-shy.

The investor declined to be interviewed for this profile or to have a spokesperson respond to questions. Fournier and fellow Greenbrook principal Frederic LeCao instead provided statements saying the firm had invested more than $100 million since 2018 “in the renovation of apartments in disrepair.”

It’s unclear when Fournier started in real estate, but since founding Greenbrook a decade ago he has assembled a sizable portfolio — 102 buildings totaling 737 units, according to PincusCo — and found a repeat partner in private equity giant Carlyle.

“He’s an ambitious guy,” said one broker who requested anonymity. “He’s been around.”

In his early career, Fournier co-managed real estate investments for the Olayan Group. By 2013 he was rubbing elbows with Starwood Capital’s Barry Sternlicht. A photo from the opening of Starwood’s Baccarat Hotel New York that year shows the billionaire Sternlicht, champagne flute in hand, opposite a bespectacled, deer-in-the-headlights Fournier.

From Olayan, Fournier jumped to East End Capital, where he directed capital markets activities, according to a bio on Greenbrook’s website. He popped up alongside Rudin Management’s Bill Rudin on a panel hosted by The Real Deal on international condo buyers.

In 2014 he went solo, forming Greenbrook, and over the next several years pieced together a Brooklyn multifamily portfolio to rival those of the borough’s big dogs.

Value-add gone bad

Until the tenant blowback in 2021, Fournier’s strategy was clear-cut: targeting “investments in poorly maintained, undermanaged and undercapitalized assets located in growth-oriented and transitional submarkets of New York City,” according to its site.

Rent-stabilized properties appeared to be an early focus. When Greenbrook settled with the state in 2022, it had 188 buildings totaling 1,000 units, “many of which are rent-stabilized,” the attorney general’s press release said.

The vast majority of those acquisitions likely predated the June 2019 rent law that made removing apartments from rent regulation nearly impossible.

Greenbrook’s website says it invests “in poorly maintained, undermanaged and undercapitalized assets located in growth-oriented and transitional submarkets of New York City”

Previously, if units became vacant, owners could raise the rent 20 percent, and convert them to market rate if the rent exceeded a certain threshold.

When the legislation banned the practice, owners who had banked on the strategy were crushed. Isaac Kassirer, for one, lost some buildings to bankruptcy just 18 months later.

But owners of buildings with a mix of regulated and market-rate apartments had options. Unregulated units can be legally cleared out when tenants’ leases expire and then fixed up to command higher rents.

Renovating, however, runs the risk of triggering harassment complaints from neighboring tenants. The attorney general’s settlement with Greenbrook noted that the firm began “significant construction projects” on properties it bought between 2019 and 2021. The A.G. cited complaints of habitability issues, unpermitted construction, lack of maintenance, harassment and failure to comply with rent regulation.

The de Blasio administration came after Greenbrook as well. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development filed two suits in December 2020, alleging tenant harassment at contiguous buildings on Fourth Street in Park Slope.

Months later, commenters on social media were labeling Greenbrook a “slumlord.”

Parkside problems

Each year scores of landlords rack up violations, get sued by the city or are shamed on the public advocate’s “worst landlord” list. But only a handful draw the ire of tenant advocates and elected officials.

Greenbrook’s play at 70 Prospect Park West secured its place in that unlucky minority.

The investor bought the 30-unit building, which is on a prime block in pricey Park Slope and overlooks the 526-acre Prospect Park, for $15 million on March 19, 2021. Tenants had long paid below-market rents for the exquisitely located if dated building. A week after the sale, Greenbrook served tenants 90-day notices to vacate.

Within a month, the tenants of 70 PPW and other Greenbrook buildings had organized as the Greenbrook Tenants Coalition. They rallied against construction harassment and called on then-City Council member Brad Lander for help. Advocates for “good cause eviction” — the right to endless lease renewals — made the case a cause célèbre.

Schumer, the Senate majority leader and one of the country’s most powerful elected officials, joined one rally, making the five-minute walk from his own Prospect Park West residence. A co-op owner, Schumer couldn’t fathom that Greenbrook could move tenants out after their leases expired, although that is standard practice in value-add real estate.

“There is nothing more despicable, despicable, than these predatory real estate equity firms trying to make illegal, in my judgment, billions of dollars on the backs of tenants,” Schumer said at the protest.

By June, a handful of 70 PPW renters had sued Greenbrook, claiming they had been charged market-rate rents for apartments that should have been regulated. Tenants of 509 12th Street, a Greenbrook property nine blocks south, lodged a similar suit in December 2021.

But the litigation ended there. Market-rate renters have little legal recourse against ejection when their leases expire, provided their landlord gives appropriate notice. Just two months after Greenbrook issued nonrenewal notices at another Prospect Park building, nearly half of the occupants had left, City Limits reported.

In its settlement with the attorney general the following October, Greenbrook agreed to fork over $100,000 to HPD and issue $7,500 rent credits to tenants in 10 buildings.

In the wake of that resolution, the uproar died out. The Greenbrook Tenant Coalition’s website has not been updated since then, and the formerly press-hungry group did not respond to requests for comment.

Although both rent overcharge suits are ongoing, some renters have discontinued their cases. The attorney for the tenants in those suits also did not reply to inquiries.

Pivot to sub-rehab

newly purchased 70 Prospect Park West in Brooklyn,

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer blasted

“predatory real estate equity firms.”

Fournier avoided joining the ranks of notorious landlords such as Steve Croman, who spent a year in jail and paid millions in fines, and Raphael Toledano, who was banned from New York real estate for five years.

Still, the experience led to a strategy shift.

Brokers familiar with Fournier say the developer took a liking to substantial rehabilitation projects. In a “sub-rehab,” an owner who renovates at least 75 percent of a rent-stabilized building in bad shape can move units to the free market.

“It’s one of the few avenues left to escape rent stabilization,” said Sherwin Belkin, a partner at Belkin Burden Goldman.

The rub is that units must be vacant. Owners who don’t want to work around existing tenants often opt for entirely empty buildings, brokers said.

Greenbrook’s deals fit that bill. In December, the firm picked up 168 Sumpter Street, in Central Brooklyn’s Stuyvesant Heights, for $1.5 million.

“It is worth noting that the six-unit building was delivered vacant,” said Haley Hasho, co-founder of brokerage Exodus Capital. “The buyer has plans for a substantial rehabilitation play.”

Many of Greenbrook’s deals with Carlyle fit the sub-rehab strategy, the anonymous broker said. Carlyle did not respond to a request for comment.

The broker said firms have moved away from those “six- and eight-unit sub-rehab deals” more recently “because the paperwork was getting questionable.” The reference was to a state agency’s effort to curtail such projects, which led to litigation and then a state law tightening the rules on sub-rehab.

Previously, the process was “self-operating, meaning if the developer did the work, the building would be exempt,” Belkin said.

Starting this year, substantial rehabs require approval in advance by the state housing agency. The Senate is still working out amendments demanded by Gov. Kathy Hochul when she signed the bill. But it isn’t expected to introduce any major changes.

Big bet on small rentals

Amid those complications, Greenbrook and Carlyle have zeroed in on buildings free from rent regulation.

“They kind of changed it up about a year ago,” the anonymous broker said.

“You buy a turnkey three-, four-family and nobody’s ever gonna come back and question whether it was done properly and throw it back into rent stabilization,” he added. Buildings with fewer than six units are not subject to rent regulation.

Carlyle has made a major move into Brooklyn’s small rental market. In the past 24 months, it has spent just shy of $1 billion on 174 properties, according to a PincusCo analysis.

Greenbrook partnered on some of those deals, which tend to be renovated properties. For example, in late January the firms nabbed a three-family apartment building in Bedford-Stuyvesant for $2 million, property records show.

The seller had bought the building, at 1113 Herkimer Street, nine months earlier for half that price. An April 2023 listing describes it as holding “great potential with some hands-on TLC,” and a current listing for a first-floor apartment calls it “newly renovated.”

Such properties typically fall into the city’s 2A/2B tax designation, which limits real estate tax increases to 8 percent a year — a perk for owners. The team has bought exclusively in Brooklyn, where new lease signings have doubled from a year ago and the median rent hovers around record highs.

But on other Carlyle deals, it appears that Greenbrook did the work, then flipped the buildings to Carlyle.

As of last June, Greenbrook had sold at least 19 properties to Carlyle affiliates over the previous 18 months, reaping 75 percent more than what it paid a year or two before, PincusCo reported.

In one of its larger deals last year, Greenbrook unloaded 140 Frost Street, 171 Cooper Street and 516 Fairview Avenue to a Carlyle entity for $9.5 million. At 140 Frost, Carlyle rented out a two-bedroom in July for $4,350, a 67 percent increase from when it last rented in 2020, before Greenbrook bought the building.

Greenbrook sold the buildings in part to pay off a watchlisted loan. The securitized debt was short-term and floating-rate, the kind of mortgage typically used for value-add projects.

Fournier, asked last year about the troubled debt, was unperturbed. The sale paid it off, he said by email, leaving the three other properties that had collateralized it free and clear.

“No debt,” he wrote. “Pure profit.”